Classical music of India

When people speak of classical music they usually mean Western classical. But India has its own classical music, a heritage of unsuspected richness. Indian classical music has its origin in sacred texts thousands of years old. It is probably one of the world’s most elaborate musical systems, so explanations can soon become very complex. This article just sets out some basics.

Origines

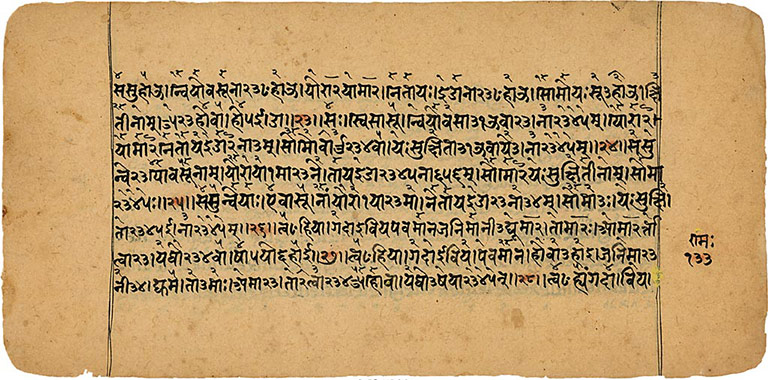

It is generally acknowledged that the Vedas, sacred texts believed to date back to the 15th century BCE, are a probable source of India’s classical music. The music would have been gradually enriched over the centuries until it morphed into the sophisticated system we know today. There are four Vedas – the Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva Vedas. It is the Sama Veda that is said to lay the basis for Indian classical music. The Sama Veda consists mainly of hymns, mantras and poetic texts, which were chanted during Vedic rituals using three to seven notes, sometimes with an instrumental accompaniment.

The basic concepts in Indian music include swara (the notes), raga (improvised melodies based on a particular set of notes), shruti (microtones), alankar (ornamentations) and tala (rhythm patterns provided by percussion instruments).

Indian music is almost never written down. It is transmitted orally from teacher (guru) to student. The “colour” of a raga varies according to the teacher or the gharana he belongs to. In North Indian (or Hindustani) music a gharana is a system of social organization linking musicians or dancers by lineage or apprenticeship and by adherence to a particular musical style or musicological ideology. The ideology can sometimes vary quite significantly from one gharana to another. It has a direct impact on musicians’ thinking and on the teaching and appreciation of the music.

Hindustani & Carnatic Music

There are two distinct styles of Indian classical music, Hindustani in the North and Carnatic in the South (Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka).

The two styles began to separate in the 12th and 13th centuries with the Mughal invasions of North India. Northern music absorbed Persian and Arab influences. Khyal and dhrupad are the two main genres of Hindustani music but there are also other classical and semi-classical genres. In the 16th and 17th centuries the division between the Hindustani and Carnatic styles became quite marked.

In South India, music remained relatively little influenced by the Persian and Arab styles. But some say the split from Hindustani music had more to do with musicological innovations in the South during this period. One of these innovations was a new system for classifying ragas, the Asampurna Melakarta, developed by the eminent 17th-century musicologist Venkatamakhi.

Although the two systems are made up of the same basic elements and can sound similar to the uninitiated ear, they actually differ considerably in style, approach and colour.

Swar: the notes

Indian music uses a gamut (saptak) of seven basic notes, SA RE GA MA PA DHA NI, like the Western DO RE MI FA SO LA TI.

To these are added five semi-tones, giving the equivalent of sharps or flats and a 12 note scale. Written down, flats are indicated by underlining the note name and (e.g. DHA) and MA’ indicates FA sharp.

SA RE RE GA GA MA MA’ PA DHA DHA NI NI SA

In Indian music the actual pitches of the notes are not fixed in terms of frequencies as they are in Western music where A is set at 440 hertz, for example. In Indian music the musician decides on the pitch of their SA and tunes their instrument accordingly. So SA could be our A, B, C etc. or anywhere in between. Once SA is set, that fixes the intervals of the other natural notes.

The Indian scale is often punctuated by ornamentations called alankar. Indian music just wouldn’t be Indian music without these glissandos and oscillations. Sometimes they are fixed by the rules of a particular raga, sometimes they stem from the musician’s inspiration. They give a particular flavour to the raga and its interpretation.

Indian music also uses microtones or shruti. These are intervals of less than a semi-tone. There are 22 in an octave. The number of shruti for each note are as follows: Sa: 4 shruti, Re:3, Ga:2, Ma:4, Pa:4, Dha:3, Ni:2.

Raga, the melodic framework

The word raga means “colour”, “tint” or “passion”. To simplify things, we can say that a raga is a particular combination of notes arranged into basic themes that provide a melodic framework. A raga is intended to evoke a particular feeling according to circumstances and the time of day. So there are morning, afternoon and evening ragas, ragas for particular seasons or events, etc.

Thaat and melakarta. As we said earlier, there are significant differences between the Hindustani music of North India and the Carnatic music of the South. Although there are overlaps, the two schools have their own ragas and classify them differently. Hindustani music considers that there are ten root ragas, called thaat, from which all the others are derived, whereas Carnatic music identifies 72 melakarta.

- Example of Thaats :

Bhairavi : SA RE GA MA PA DHA NI SA

Bhairava : SA RE GA MA PA DHA NI SA

Kalyan : SA RE GA MA’ PA DHA NI SA

In the music of northern India the raga consists of a minimum of 5 notes in one of 10 thaats, each thaats has 7 swara or notes.

- Example of Melakartha :

SA RE1 GA2 MA1 PA DA1 NI2 SA

SA NI2 DA1 PA MI1 GA2 RE1 SA

Raga of a Melakartha :

SA RE1 MA1 PA DA1 SA

SA NI2 DA1 PA MA1 GA2 RE1 SA

Tala, the rhythmic system

A tala is a rhythmic structure in the same way that a raga is a melodic structure. A tala can be regarded as a cycle of beats.The most important beat in a cycle is the first, called sam. The percussionist’s improvisational patterns start and end on the sam.

The tala is enriched by the different ways in which the tabla, mridangam or other percussion instrument can be struck to produce different sounds. North and South India each have a lexicon of mnemonic syllables for naming these sounds, called bol in the North and konnakol in the South.

In the South, vocalising konnakol is a highly respected and appreciated art in its own right. It is said that in the old days reciting the konnakol was more important than mastering the mridangam itself.

- Example of Bol:

Teen tal – 16 temps (4+4+4+4)

syllabes : dha dhin dhin dha /dha dhin dhin dha /dha tin tin dha /dha dhin dhin dha

- Example of konnakkol :

1 temps, Thom

2 temps, Ta Ka

3 temps, Ta Ta Ki

4 temps, Ta Ka Di Mi

5 temps, Ta Di Gi Na Tom

Example of phrases: TakKiTaTaKiTaTaKa (3 + 3 + 2), ou TaKaTaKaTaKataka (2 + 2 + 4)

In Carnatic music, the tala is also indicated visually by a series of rhythmic hand gestures called kriya. These are used rather like ways of beating time in Western music.

The Indian classical concert

- Hindustani music

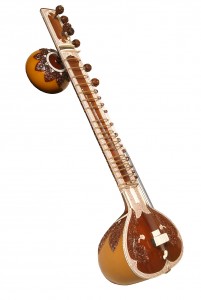

Concerts are generally given by small groups of musicians: the singer or instrumentalist, an accompanist (at least for vocal music, and often on harmonium), a percussionist (tabla for the khyal genre, mrindangam for drupad), and a tampura to provide the drone. Other typical instruments used in these performances include the sitar, sarod, santoor and sarangi.

The performance usually begins with alap, a kind of introduction – a slow unfolding of the raga without percussion. This may be very brief or may last half an hour, depending on the singer’s inspiration. In vocal music the alap is followed by a bandish, a composition set in the same raga and generally accompanied by the tabla. With instrumental music the alap is followed by a more rhythmic piece called jod and then a fast-paced piece called jhala.

- Carnatic music

Carnatic music puts the emphasis firmly on vocal music and the devotional aspect. The group consists of the principal performer (usually a singer), a melodic accompanist (usually on violin), a percussionist (usually on mridangam), and a tampura player for the drone. Other typical instruments used in these performances include the ghatam, kanjira, mouth harp, bansuri flute, veena and chitraveena.

Carnatic concerts generally last three hours. The structure of a typical concert was established by the singer Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar (1890–1967). The opening piece, a kind of warm-up for the musicians, is called varnam. Then comes a prayer for blessing and a series of exchanges between the raga and the tala, with hymns called krithi. These are followed by the pallavi or raga theme.

Main instruments of classical indian music

The voice is regarded in India as the first musical instrument.

Thank u for this well written brief on Indian classical music. It serves to explain the overall structure of the subject in a simple n systematic manner. Praises to the author.

P.S: Plz also mention all thaat names n instrument names below their pic if possible.

Thanks Mukul for your kind message. yes sure good idea, I’ll add the names of the instruments. regards, Mathini

I like Indian classical music

Tks 🙂

Great!

thanks 🙂

nice

thanks 🙂

Thanks for this post

Thanks 🙂

Very elaborately written article. Full of information . Thanks for publishing.

Thanks Amitava Nath ! 🙂