Indian cinema

There can be no discussion of Indian culture without mention of Indian cinema. India produces more films than any other country – nearly 1000 a year, screened in more than 10,000 cinemas and attracting some 30 million cinema-goers per day! Film industries around the world can only envy such dizzying statistics.

Indian cinema, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2013, can surprise and puzzle those new to it. For many years it was confined to the subcontinent plus a small handful of Indiaphiles, but in recent decades Indian films have attracted considerable notice at film festivals and in cinemas in the West. From the musicals (commonly but inaccurately known as Bollywood) to art films, Indian cinema is a world apart.

A Brief History

The films of the French Lumière brothers were screened in Bombay (today’s Mumbai) in 1896. Over the next few years several short films were produced in India, such as The Flower of Persia (1898) by photographer Hiralal Sen and a documentary called The Wrestlers (1899) by HS Bhatavdekar.

Raja Harishchandra (1913)

The first feature film acknowledged as such was Raja Harishchandra (1913), a silent film inspired by the Indian epic of the Mahabharata, with text in the Marathi language (Maharashtra, Mumbai). It was directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke, who is regarded as the father of Indian cinema. It was a big box-office success and marked a key point in the history of Indian cinema, paving the way for other films in regional languages.

The first cinemas were built and in the 1920s cinema-going became popular owing to the cheap ticket prices.

Alam Ara (1931), first Indian talkie

In 1931 Ardeshir Irani made the first Indian talkie, Alam Ara, followed by Kalidas in Tamil and Telugu.

With technology and sound recording improving constantly, in the 1930s the first musicals were released, such as Indra Sabha and Devi Devyani. This was the beginning of song and dance in Indian films.

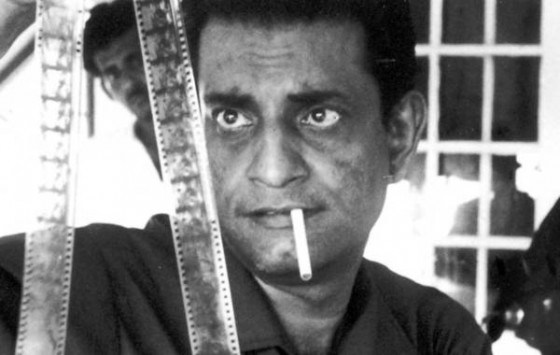

Satyajit Ray

Neecha Nagar

In the 1950s a Parallel Cinema movement emerged in West Bengal as an alternative to the mainstream commercial films. These art films attracted critical notice and won prizes at the big European film festivals. Neecha Nagar, a social-realist film by Chetan Anand, had won the Grand Prix at the first Cannes festival in 1946. Satyajit Ray won the Golden Lion at the Venice Mostra with Aparajito (1956).

The golden age of Indian cinema lasted from independence to the 1960s. The films most highly acclaimed by critics and audiences were produced during this period.

The ’70s saw the growth of commercial film production and the rise of the first “Bollywood” stars such as Sridevi, Aamir Khan, Madhuri Dixit, etc

What is Indian Cinema?

Tamil movie “Thiruttu Rail 2015”

First of all, there is not just one “Indian cinema” but several regional film industries in their respective languages. The best known are Hindi (North India), Bengali (West Bengal in Northeast India), Tamil (in Tamil Nadu, Southeast India), Telugu (Andhra Pradesh, South India), Kannada (Karnataka, Southwest India) and Malayalam (Kerala, Southwest India). All these brands of cinema share a number of traits in common (music, dance and melodrama) but with a sprinkling of local culture.

Broadly speaking there are two genres of Indian film: musicals better known as Bollywood* films, and art films or Parallel Cinema.

* “Bollywood”, a name formed from “Bombay” and “Hollywood”, mainly refers to Hindi language films made in Mumbai (Bombay). In fact only about 30% of the thousands of films made in India each year are made in the Mumbai studios, but that is where the musicals film genre was born.

Bollywood movie, Hindi

Bollywood cinema freely mixes different genres in one film, spiced up with music and dance filmed in picturesque places to which the actors are suddenly teleported. To the Western eye this type of film is totally illogical and improbable – but oh, so Indian! The films of the last decade, however, have tended to be more realistic.

The Music in Bollywood movies

In most Bollywood films the music is of prime importance and can make or break a film. The songs are released long before the film. “Filmi” music, as it is called, sometimes plays a narrative role in the film while also adding a festive element.

It has to be said that a trip to the cinema is, for much of India’s population, a recreational moment – as any Westerner who has been to see a film in India will remember. “Shh!” would be totally out of place. Indian audiences live every moment of the film, picking up the dance moves and songs, applauding and vocalising unrestrainedly. This too is typically Indian. An indian musical lasts three hours with an interval halfway through (true!) and may have five or six song-and-dance numbers at various points through the film.

[ A 2014 example of the Bollywood genre is Lovely with Deepika Padukone and Shah Rukh Khan ]

Unlike Western musicals where the actors make a point of singing the songs themselves, this is not expected of Indian actors, who lip-sync to the voices of professional playback singers.

Lata Mangeshkar

The quality of the compositions varies widely but when the songs make a hit with the public the singers concerned become stars on a par with the actors. Among the most famous are Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammed Rafi and Kumar Sanu among the older ones and Atif Aslam, Arijit Singh and Alka Yagnik in the new generation.

Parallel Cinema

Parallel Cinema, or New Wave cinema, is at the opposite pole to Bollywood films. It is elitist art cinema, realistic, naturalistic and with a keen eye on the socio-political climate of its time. It accounts for no more than 10% of the films produced in India and is often seen only by intellectuals, upper class students and Western middle-class film buffs.

The first social-realist films were produced in the 1920s and ’30s. One of the first was Baburao Painter’s 1925 Savkari Pash, about the plight of poor farmers. In 1937, V. Shantaram’s Duniya Na Mane (The Unexpected) critiqued the situation of women in Indian society.

In the 1950s there was an art film movement in West Bengal, with filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak who became world famous. Art cinema then spread to other regional film industries and won many prizes at international film festivals.

Subjects

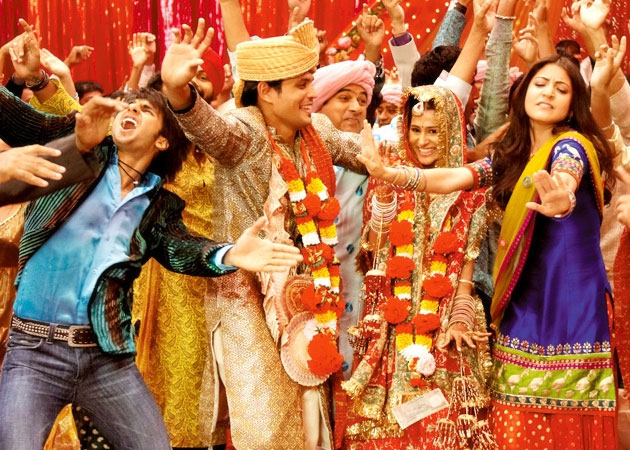

Marriage, one of the most favourite subjects of Bollywood movies

Bollywood films often reflect the stereotypes of Indian society. The family, romance and marriage are recurrent themes.

Many Bollywood films also deal with India’s history and politics, with themes like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, the Mughal Empire, the British Raj, the partition of 1947. Whatever the theme, heroes and heroines are the focus. India loves a hero!

Parallel Cinema, as we saw above, addresses social issues, which can be extreme in India: the underworld, corruption or the condition of workers, women or outcasts, for example. When art cinema was taking shape in India in the 1940s and ’50s, the movement was particularly influenced by Italian Neo-Realists such as Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thieves, 1948) as well as the French New Wave and filmmakers such as Jean Renoir (Le Fleuve, 1951).

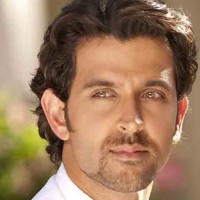

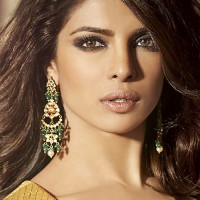

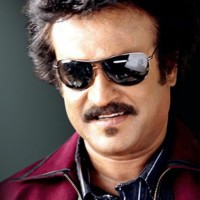

Actors & Actresses in India

Actors and actresses in India are stars in the fullest sense of that term, regarded as heroes in their own right. Words like “superstar” and “megastar” are liberally thrown around. “Superstar Rajnikanth”, unchallenged king of Tamil Nadu cinema in South India, is one example. Their pay matches their status: in 2015, Forbes magazine’s top 10 highest-paid actors included Indian actors Amitabh Bachchan and Salman Khan in 7th place with $33.5 a year, followed by Akshay Kumar and Shah Rukh Khan. Their incomes derive from their actors’ salaries, sales of film rights to TV channels, and product advertising.