Folk music

India’s incredible cultural diversity has produced innumerable different style of folk arts. Every state in India has its own folk traditions.

Indian folk music is passed down from generation to generation in a family or community and is played or sung at religious festivals and rites of passage such as births, marriages and deaths.

Most of the instruments used in folk music are different from those used in classical music. A few, like the tabla, harmonium and the sarangi, are common to both.

Here is a selection of Indian folk music.

Music of Rajasthan

Rajasthan has a diverse collection of musician communities, including langas, saperas, bhopas, and Manganiyars.

LANGAS

The Langas are a community of professional musicians who usually live in West Rajasthan (Barmer, Jaisalmer and Jodhpur) and in the Kutch region in Gujarat.

They are divided into two types depending on the instruments they play: the Surnaiya Langha play wind instruments such as the shenhai, murali, surnai and algoza, while the Sarangya Langha play the sarangi, a bowed string instrument.

The Langhas are thought to have come originally from the Sindh region (now in Pakistan) and to have converted to Islam in the 8th century when the Mughals conquered Sindh.

They usually play for the sindhi-sipahi, a Rajput Muslim community who are their traditional jajmans (patrons), but in recent decades the Langhas have become standard-bearers for Rajasthani culture and often play at festivals in India and around the world. Many of their songs are connected with rites of passage.

MANGANIYARS

The Manganiyars are similar to the Langhas and are also highly reputed Muslim professional musicians. Their songs are passed on from generation to generation.

They used to be under the patronage of rich merchants in caravan towns and, more recently, of the Hindu Rajput community. Most of them live in West Rajasthan.

Their preferred instrument is the kamaicha fiddle, with dholak drum and dhadtal castanets for the rhythm section. Like the Langhas, they play at major festivals in India and abroad.

BHOPAS

The Bhopas are musicians who sing the praises of Pabu, a folk deity who acts as mediator for the problems of everyday life.

The musicians play in front of an unrolled scroll called a phad painted with scenes from the life of Pabu. This acts as a portable temple. The Bhopas play a traditional bowed stringed instrument called a ravanhatta.

SAPERAS

Once professional snake handlers, saperas today evoke their former occupation in music and dance that is evolving in new and creative ways.

Since the enactment of the Wildlife Act of 1972, the sapera have been pushed out of their traditional profession of snake handling. Today, performing arts are a major source of income for them and these have received widespread recognition within and outside India.

They use the different instruments such as the pungi, a woodwind instrument traditionally played to capture snakes, the dufli, been, the khanjari – a percussion instrument, morchang, khuralio and the dholak to create the rhythm on which the dancers perform.

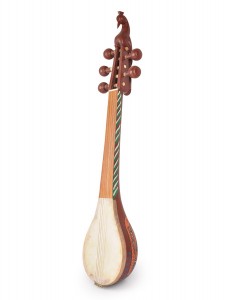

Some of the instruments used in Rajasthani music

Baul music

The Bauls are mystic minstrels living in rural Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. The Baul movement was at its peak in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and has now become popular again among the rural population of Bangladesh. Their music and way of life have influenced a large swath of Bengali culture, most powerfully the compositions of Rabindranath Tagore.

Bauls live either near a village or travel from village to village and earn their living from singing to the accompaniment of the ektara, a simple one-stringed instrument, and a drum called dubki. Bauls belong to an unorthodox devotional tradition, which has been influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism, Bengali Vasinavism and Sufi Islam, yet it is distinctly different from these.

Bauls do not identify themselves with any organised religion nor with the caste system, special deities, temples or sacred places. Their emphasis lies on the importance of a person’s physical body as the place where God resides. Bauls are admired for this freedom from convention as well as their music and poetry.

In 2005 they were declared as “Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” by UNESCO.

source : www.unesco.org

Pandavani

Pandavani (lit.: Songs and Stories of the Pandavas) is a folk singing style involving narration of tales from the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata. The singing also involves musical accompaniment. Bhima, the second of the Pandava is the hero of the story in this style.

This form of folk theatre is popular in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh and in the neighbouring areas of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh.

During a performance, as the story builds, the tambura becomes a prop, sometimes to personify Bhima’s ‘gadaa’ mace, or Arjun’s bow or chariot, or the hair of queen Draupadi or Dushasan thus helping the narrator-singer play all the characters of story.

The form does not employ any stage props or settings. With the use of mimicry and rousing theatrical movements, once in a while the singer-narrator breaks into an impromptu dance at the completion of an episode or to celebrate a victory in the story being retold. The singer is usually supported by a group of performers on Harmonium, Tabla, Dholak, Manjira and two or three singers who sing the refrain and provide backing vocals.