Batik in Kutch, the print of ancestral know-how

Batik is among the most vibrant textile arts of Kutch, alongside ajrakh, bandhani, and the distinctive embroideries of the Ahir, Rabari, and Mutva communities. This art, woven into the very fabric of Kutch’s land, is a profound mirror of its history and the ancient trade routes that have shaped its identity.

History of batik

Batik, a wax dyeing technique more than 2,000 years old, has origins that remain uncertain but is widely believed to have reached its peak in Java, Indonesia, where it became a culturally profound art.

From Java, batik spread worldwide. In India, the technique became well-established, with Gujarat becoming a major center, especially the Kutch region. Other states such as West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh also adopted it. Its arrival in India was via trade routes and through initiatives such as that of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, who brought Javanese artists to teach batik.

In Kutch, as early as the 1500s, this highly prized shimmering fabric crossed the seas from the bustling port of Mandvi.

However, the 1960s marked a turning point. Batik’s appeal faded, supplanted by the rise of more affordable manufactured fabrics. But the spirit of Kutch’s artisans remained strong. With remarkable resilience, they continued to shape wax and colors, skillfully incorporating modern motifs to breathe new life into this ancient art. Batik, like a phoenix, reinvents itself, proving that tradition can still dance with modernity.

Today, the town of Mundra, 50 km south of Bhuj, is the beating heart of batik in Kutch, where around twenty artisans perpetuate this ancient art. I had the privilege of meeting Shakeel Ahmed Khatri, an essential master of batik, who took the time to explain this printing technique to me, despite a very busy schedule.

Manufacturing process

Unlike ajrakh, batik is a staged dyeing art where wax (often a mixture of paraffin and beeswax) plays a central role. It is precisely applied to white fabric, either using carved wooden blocks or delicately by hand.

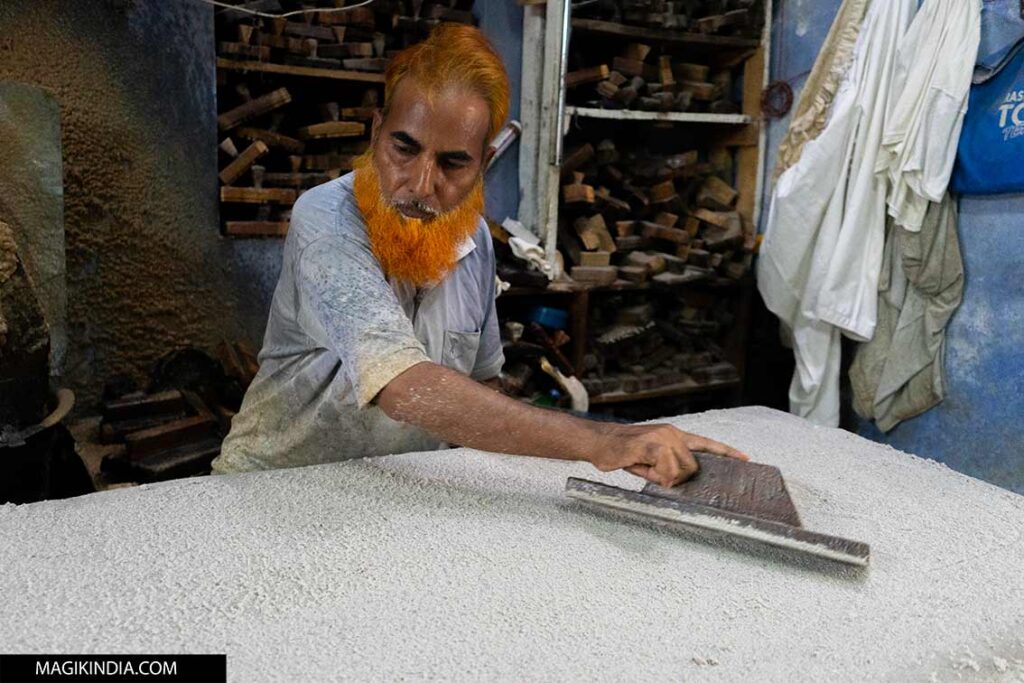

Preparation begins with a thorough washing of the thick cotton fabric. The fabric is then laid on wet sand, previously tamped with a wooden trowel.

The sand is essential: it absorbs excess heat, preventing the wax from spreading and ensuring the accuracy of the pattern.

The creation phase can then begin, with the application of the patterns using various wooden stamps

Then the magic happens: when the fabric is immersed in the dye bath, the wax acts as a shield. It “reserves” the areas it covers, preventing them from absorbing the color. The rest of the fabric, however, is impregnated with the dye.

This ballet of waxing, dyeing, and washing can be repeated several times, layer upon layer, to create multi-colored fabrics and intricate patterns. One of the unique signatures of batik is the appearance of fine “veins” or “crackles,” formed by the wax subtly cracking, adding an inimitable texture to the final design.

According to Khamir, an organisation dedicated to preserving Kutch’s rich heritage, the art of batik was once shaped by a unique method: a block was dipped into hot piloo (salvadora persica) seed oil and then gently pressed onto the fabric. Once the dyeing process was complete, this oily paste was removed, revealing the print.

However, over time, wax became the heart of the batik method. Much more practical to use than pilou oil, the extraction of which required the pressing of thousands of tiny seeds, wax simplified and perfected this ancient craft, but also changed the appearance of the print by creating a veined effect.

If you are interested in these art forms, we organise personalised workshops with master artisans, including Batik, Ajrakh, and embroidery, in Kutch, as well as throughout Gujarat. Contact us!

MEET THE FASCINATING ARTISANS OF KUTCH