The Arts of Kutch Region, Gujarat

Bordered by Pakistan and Rajasthan, Kutch is an ancient land that takes its name from its turtle-like geographical features (Kachchh in Gujarati). This region has developed its artistic richness by integrating the knowledge and traditions of the myriad of communities that have settled there since Antiquity: Rabari, Jats, Ahir, Meghwal, Sodhas, to name a few. In addition, due to the existence of major ports (Mandvi in particular), Kutch was once the epicenter of maritime trade, which extended from Central Asia to the west coast of Africa and India via the Middle East. This trade route also brought its share of outside influences to the Kutch region.

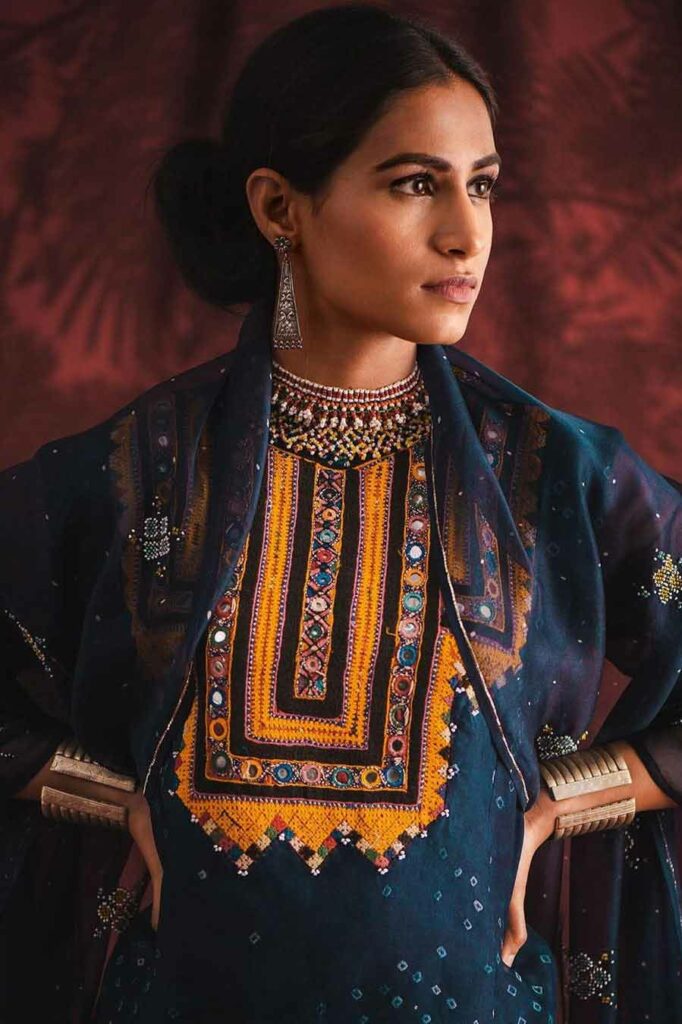

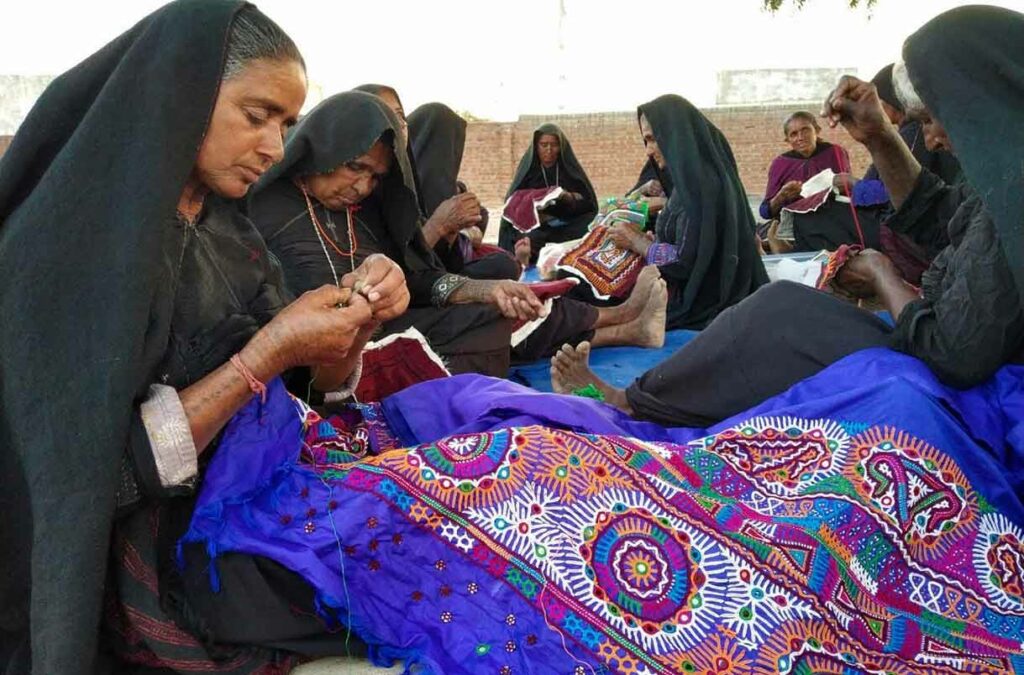

Embroidery, the quintessential art of Kutch

Embroidery is certainly the most emblematic craft of the Kutch region and mainly the Abhla, which incorporates small round mirrors.

Originally, the art of embroidery, transmitted from mother to daughter, served a purely utilitarian purpose: embroidered garments were essentially intended for the bride’s trousseau.

This art is now exported all over the world and many renowned designers are inspired by it for their own creations; this is the case of Aratrik Dev Varman from the Tilla studio in Ahmedabad.

We can say that there are as many styles of embroidery in Kutch as there are peoples, about twenty. They reflect membership in a community and the status of individuals within this same group.

Thus, the Rabaris women use the chain stitch and the inclusion of small round mirrors to create brightly colored geometric patterns inspired by their semi-nomadic life and ancestral myths.

As for the Meghwal women, they use the “paako” style or buttonhole stitch with the incorporation there too of small mirrors. The patterns of the paako are mainly floral and arranged symmetrically.

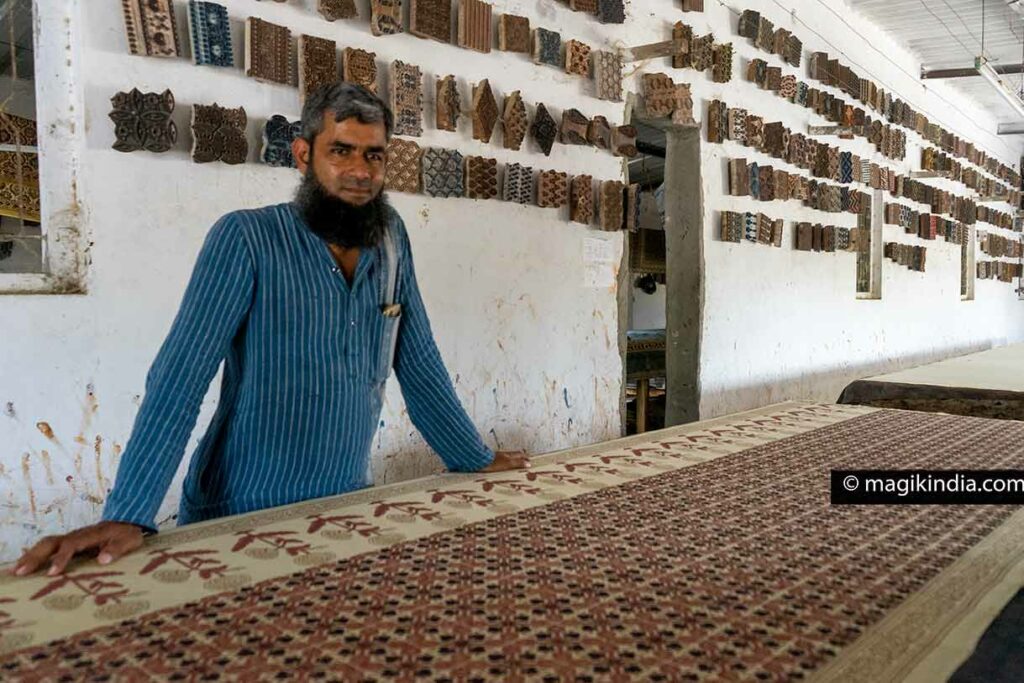

Ajrakh, the block printing

Ajrakh is also a very popular craft in Kutch. Generally concentrated in Ajrakhpur, we also find this art in small villages scattered here and there near Bhuj (prefer these small artisans).

It consists of printing repetitive patterns on a fabric using carved wooden blocks soaked in ink.

The art is very old. It dates back to the civilizations of the Indus, nearly 3,000 years BC. However, this printing technique particularly flourished under the patronage of kings in the 12th century of our era.

It is a demanding job, no less than twenty steps are necessary until the final printing of a fabric. This involves, among other things, the careful carving of the matrix (the wooden block), the preparation of inks traditionally made from natural pigments, the manual application of the blocks to the cotton fabric and soaking, rinsing and drying.

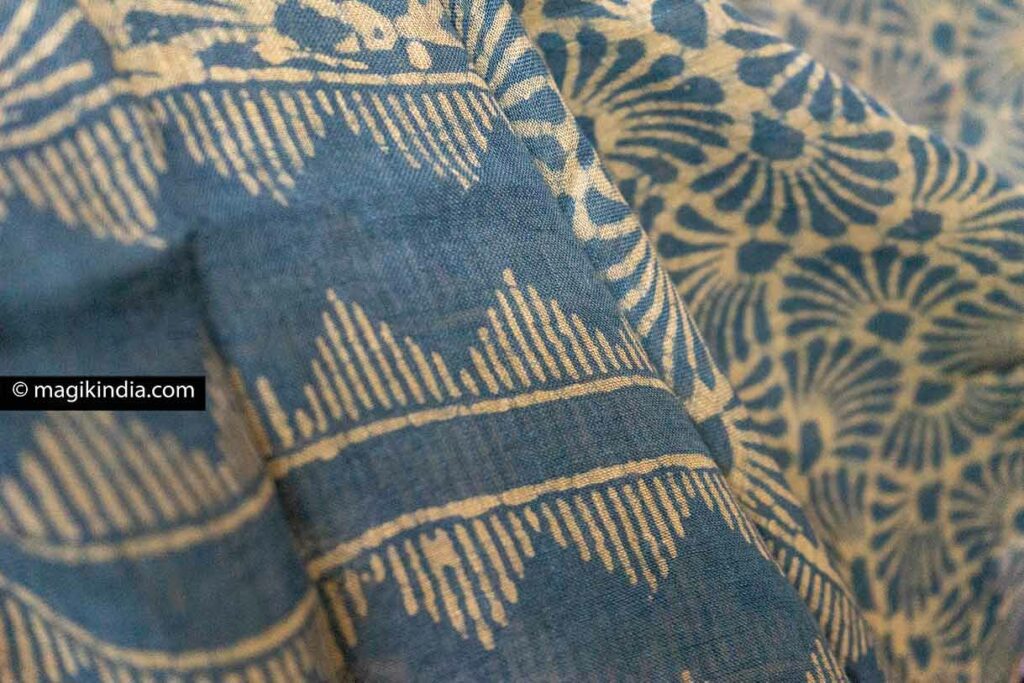

Batik, block printing with wax

Batik, like Ajrakh, is a woodblock printing technique. The major difference here is the use of hot wax on the blocks instead of the usual ink.

The principle of Batik consists in protecting areas of the fabric against staining by delimiting them with hot wax. The fabric is then soaked in several successive dye baths until the desired color is obtained. At the final stage, the wax is removed by soaking in boiling water.

This type of printing, which is also found in Indonesia and Africa, gives a “cracked” and textured effect to the fabric.

Bela, an endangered form of block printing

The Bela takes its name from the village of the same name near Rapar Taluka in Kutch. It is a dying art, as only one craftsman, Mansukhbhai Khatri, now practices it.

This technique is done with smaller blocks of wood than Ajrakh or Batik and the design, which is usually done on a plain white background, is very graphic with two iconic natural colors: red and black.

Bandhani tie-dye

Bandhani is a type of textile printing called “tie-dye” whose manufacture is located not only in Gujarat, but also in Rajasthan, Punjab and Tamil Nadu where it is known under the name Sungudi.

If this technique was widely popularized by the hippies in the 70s, its origins are very old: they date back to the Indus civilization. The earliest such example can be seen in one of the 6th century paintings in Ajanta number 1 cave depicting the life of the Buddha.

Bandhani’s art is a meticulous process. The technique consists of dyeing a fabric which is first tied at several points; these knots or “Bhindi” which can be counted in the hundreds on the same piece of fabric form a harmonious geometric design once removed after dyeing. The variety of patterns depends on how the fabric was tied.

Rogan, oil painting

The Rogan, is an absolutely unique fabric painting method! Originally from Persia, it arrived in the village of Nirona (Kutch), about 400 years ago.

Just like the Bela, there is only one family of craftsmen that perpetuates the Rogan tradition. This art was on the verge of extinction when, in the 1980s, the Abdul Gafur Khatri family decided to save it and develop it. Their effort was rewarded in 2019 with the prestigious Padma Shri, which is a civil decoration awarded by the Indian government to those who have distinguished themselves in various fields such as the arts.

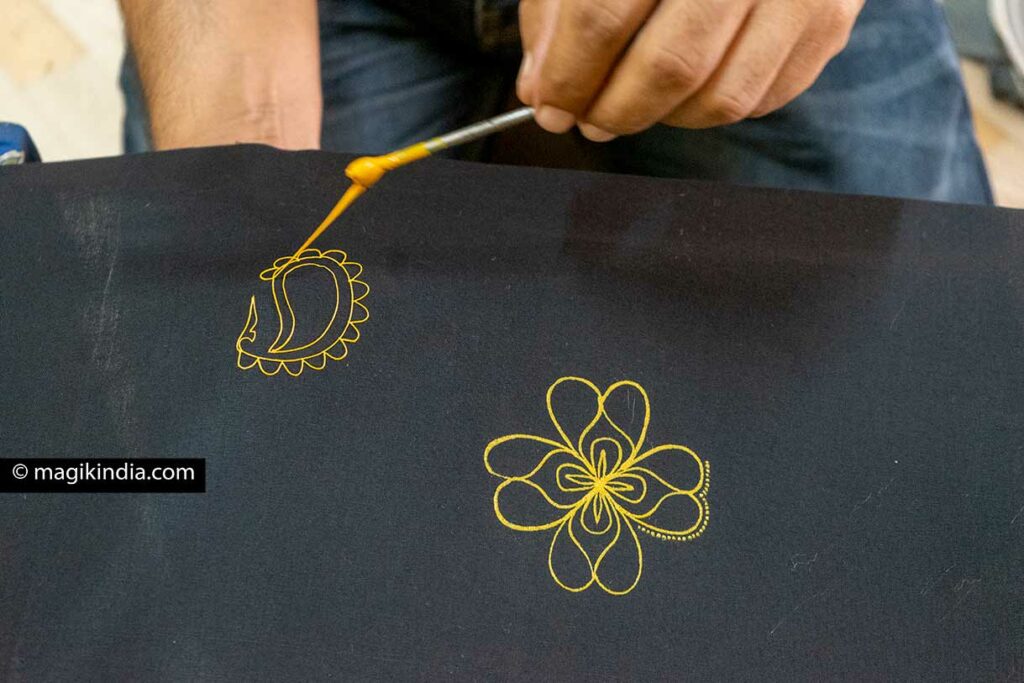

In the Rogan, elaborate drawings are made “freehand”, applying thin lines of paint with a stylus. Usually half of a design is painted, the fabric is then folded in half, transferring a mirror image to the other half of the fabric.

The paint is made from castor oil (the name “Rogan” means “oil paint”) which is boiled for about two days. Then natural pigments and a binding agent are added. The paste thus obtained is gelatinous and can then easily cling to the fabric.

Traditionally, floral and geometric patterns are used in the Rogan and in particular the very popular “tree of life”.

Traditional kutchi weaving

Weaving, like embroidery, is an integral part of the Kutch region.

Kutchi weavers are traditionally from the Marwada community. It is believed that 500 years ago the Marwadas of Rajasthan migrated to the Kutch region and are known today as the Vankar.

In the past, the Vankars were in a symbiotic relationship with the other communities in the region. Thus, the Rabaris (pastoral people), provided them with sheep, goat or camel wool; the Ahir farmers for their part provided them with cotton.

In return, the weavers made their blankets, fabrics and traditional clothing (veils, skirts and shawls).

With the industrialization of textiles in the 1960s and 70s, local demand dwindled considerably and local crafts almost died out. The Vankars then grouped together in a cooperative of weavers located in Bhujodi. It is a destination that has become very (too) touristic at present; as weavers are present almost everywhere in the region, it is better to favor a small village workshop which has still kept all its charm.

Ghantadi, the making of bells

In the villages of Zura and Nirona, the “lohars” (community of blacksmiths) still perpetuate the tradition of Ghantadi, the manufacture of metal bells. This art, which is said to have originated in Sindh (present-day Pakistan), was basically linked to cattle breeding, the breeders could identify and locate their herd from a distance.

The raw material for the manufacture of the bells are simple rusty iron plates purchased from recycling centers. Everything is then shaped by hand, using simple tools.

While the Ghantadi is less and less used for livestock, it is however gaining popularity as a decorative object or musical instrument.

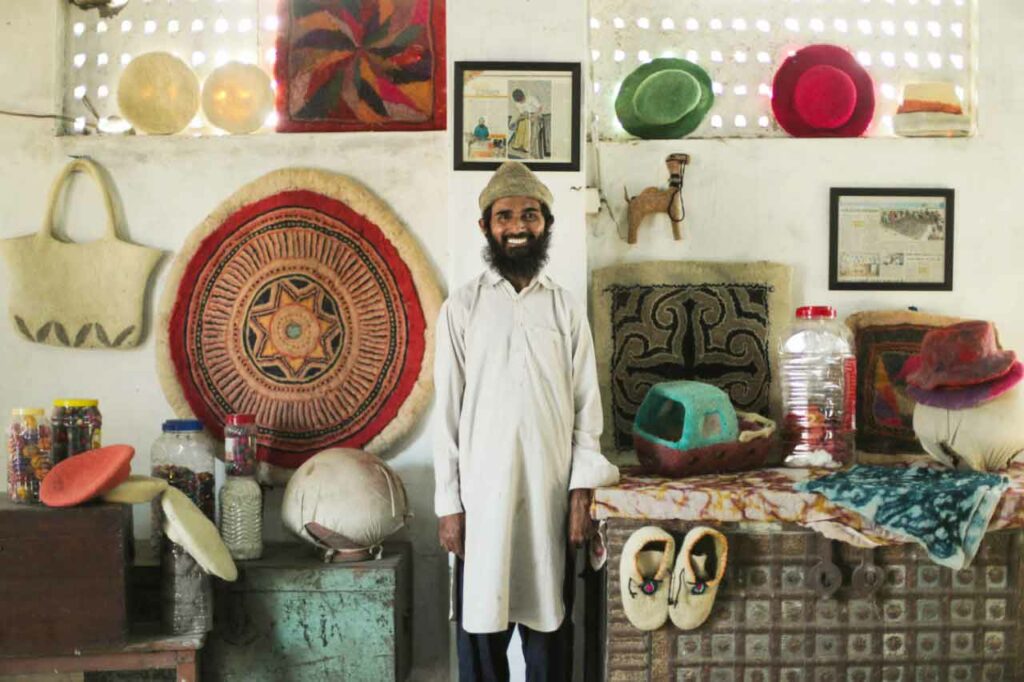

Namda, the art of wool felt

The Namba is believed to have originated in the 11th century during the reign of Mughal Emperor Akbar, when a craftsman created a felted sheep’s wool blanket for the king’s sick horse.

Since then, this craft is still used to make saddle blankets for horses and camels in local communities as well as modern creations for a wider audience like rugs, bags, hats, among others.