Ayyanar, the rural temples of Tamil Nadu

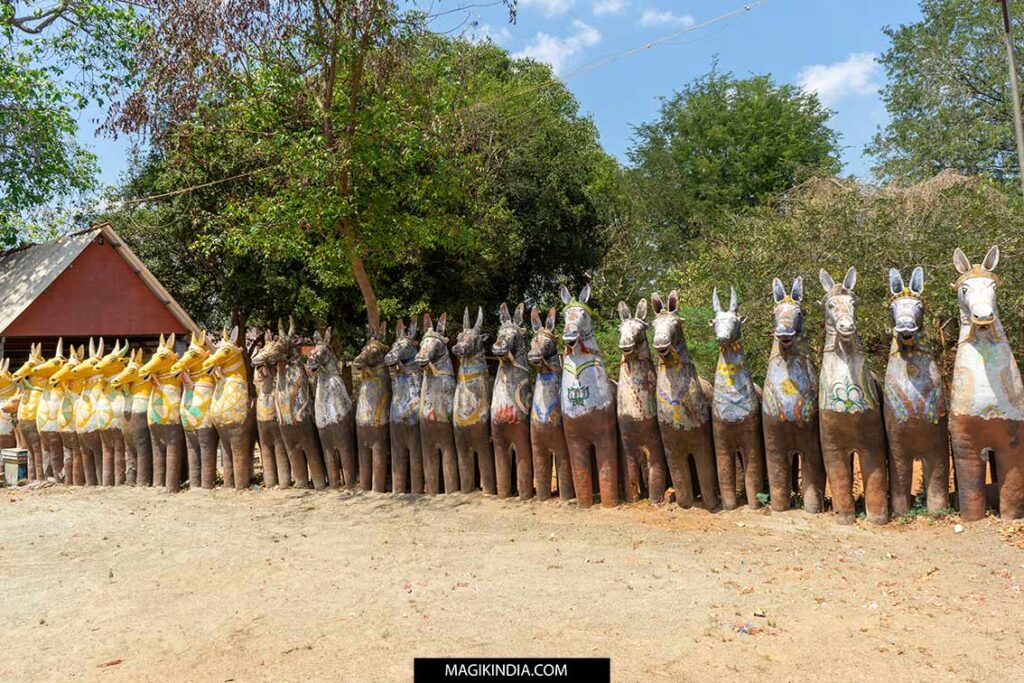

While wandering through the rural landscape of Tamil Nadu, you may have already come across this astonishing string of smiling horses, lined up proudly around a sacred tree: these are the votive images of the temples dedicated to Ayyanar, the protective deity of villages, whose worship dates back to pre-Vedic times.

Ayyanar, ancient animist rite ?

Every time I visit the Ayyanar temples in Chettinad, the same feeling always emerges within me: this cult is surely older than one might think and probably linked to pre-Vedic animist rites of abundance and fertility.

As proof of this, I would like to point out the sanctuaries of the Adivasis (indigenous peoples of India) in Poshina or Chhota Udepur (Gujarat), to name but two, where we find these ceramics of aligned horses, certainly smaller in size, but always with this aim of offering and protection.

The origins of Ayyanar are shrouded in mystery, especially since this cult has assimilated several religious and cultural influences over the centuries.

Some believe that Ayyanar is a pre-Vedic Tamil deity that evolved from the Dravidian cult of Shakti as a nurturing and protective goddess.

For others, she was the chief deity of the rulers (Pandyas, Cheras and Cholas) who ruled during ancient Tamilakam, a region covering Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Pondicherry, Lakshadweep and the southern parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

Ayyanar and Hinduism

Over time, a syncretism took place and indigenous beliefs merged with Brahmanism. Thus, in the 7th century AD, Ayyanar presented himself as the son of Mohini (the female avatar of lord Vishnu) and lord Shiva. Thus, reconciling the two Shaivist and Vishnuite clans.

The god is also associated with the deity Ayyappan, the latter also having the same progenitors. Ayyappan is a deity from Kerala who is worshipped for his ascetic devotion to Dharma, the ethical and righteous way of life.

Like Ayyapan, Ayyanar is often depicted as celibate. For this reason, in many Ayyanar temples, only postmenopausal women are allowed access to the main sanctuary.

Symbolism of Ayyanar

The name “Ayyanar” is derived from the Tamil word “Ayyan,” which means “elder” or “lord; Ayyan is, moreover, a polite formula used for deities and elders. Ayyanar is therefore perceived as an elder brother who is responsible for protecting his devotees.

It is said that the god, mounted on a white horse, patrols the village to ward off evil spirits. This is why Ayyanar temples are always built on the outskirts of villages.

Ayannar is usually accompanied by 21 other mythological figures like Karuppuswami and Veeran who help him protect the village.

Like a warrior, Ayyanar has a robust build. He carries a sword, a whip, or a club symbolizing his strength and the punishment he inflicts on anyone who dares to disturb the serenity of the village.

He is sometimes seen with his two wives, Poornam and Porkamalam, although as seen above, he is usually depicted as a bachelor.

The offerings

As a sign of devotion, worshippers offer him clay animals, mainly horses, but also cows, dogs, and elephants, to name a few. Small votive statuettes of men and women are also presented to him.

These images are made by the velars, a specific community of “potter-shamans”.

In a sacred two-day ceremony called “Kutirai Etuppu” (consecration of the horse), the velars bring the terracotta offerings to life; this involves special rituals, processions, trances, and sometimes even animal sacrifices.

The statues are then placed in a shrine. They remain there until they are eroded by time. The clay returns to dust and gradually returns to the earth, like any cycle of life.

These ancestral animist rituals could well die out, as the Velars are becoming less and less numerous; the younger generation, in fact, has little interest in this profession which is undervalued and not very financially satisfying.