“Bastar – Pictures from the Past I”, by Prosenjit Dasgupta

Magik India welcomes a guest writer, Prosenjit Dasgupta, author of the book ‘Chasing a Dream – Journeys into the heartland of Tribal India’ where he shares the stories of his travel experiences in the Adivasi region of Bastar, Chhattisgarh, from 70s to 90s.

“This story has a dream-like quality even after nearly forty years, when these journeys took place, almost on a whim. It began one summer afternoon in 1965, nearly fifty years ago, in the reading room of a library, and though it started off almost like a day-dream, it quickly had to encounter real people and real situations. The travels were to places and people so far away in time and space, and who have been so long outside the public gaze and attention that one never quite knew when the dream ended and reality intervened. Of course, these regions of India are now better known, and unfortunately for the wrong reasons.”

This is how my book, “Chasing a Dream – Journeys into the heartland of Tribal India” (published in 2014 by CinnamonTeal Publishing) begins. It records my impressions and experiences of travel and tours in Bastar, now a part of the state of Chhattisgarh, between 1970 and 1992. Bastar is now known to many people and as the book has it, for the wrong reasons; for, the region is seen to be a major focus for left-wing extremism.

But back in the 1970s it was not so and the people of Bastar, especially of the major central part of it near and around what were then the villages of Kondagaon and Narainpur, were some of the kindest and finest that one could come across. It was of course a struggle against the elements, of a stony soil, large swathes of forests and hills, frequent draughts, etc. But is the midst of it all, there was camaraderie, there was song and dance, worship of strange gods, birth and death.

Each year I would go back to Bastar, not so much because of tourist spots – and there are many of them – but for the people. I had made friends with an Adivasi boy and his family, of the Gharwa community, and would spend days with them, sharing their thatched hut and their pains and pleasures. I would go out with my friend into the villages both near and far and see the life of the tribal people, the Muria and the Hill Maria, the latter from the hills and forests of Abujhmarh, which was a strange and forbidding place, and now, unfortunately, a centre of extremism.

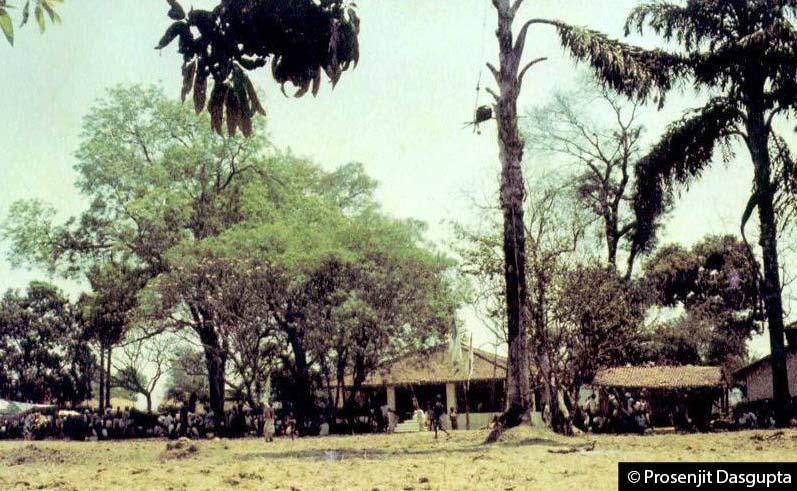

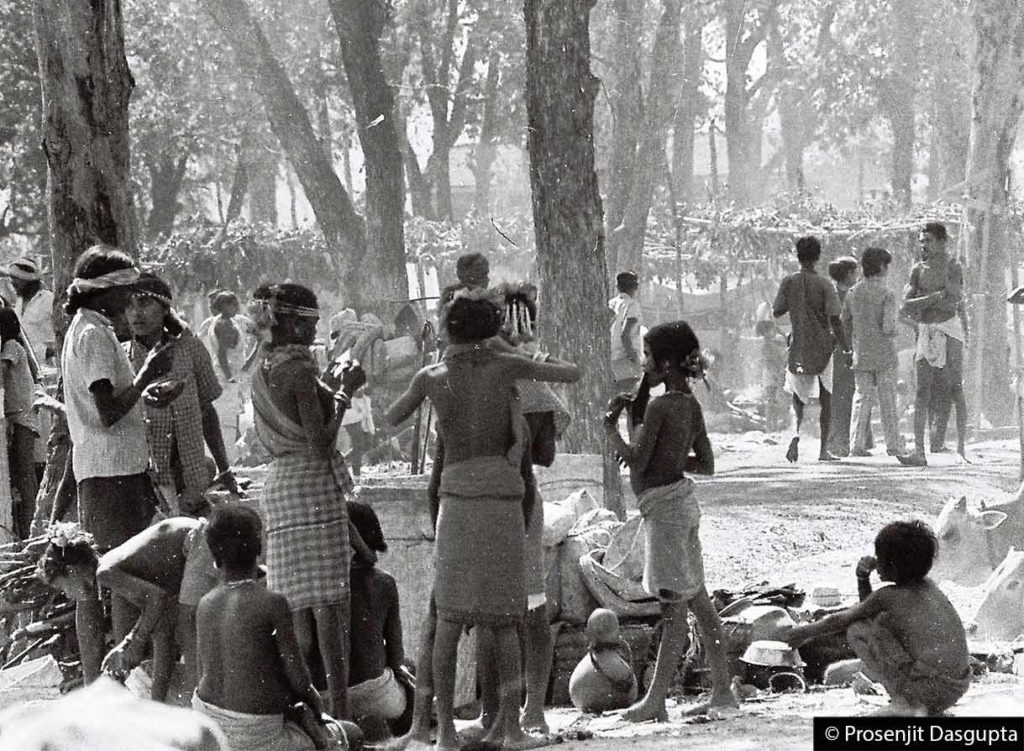

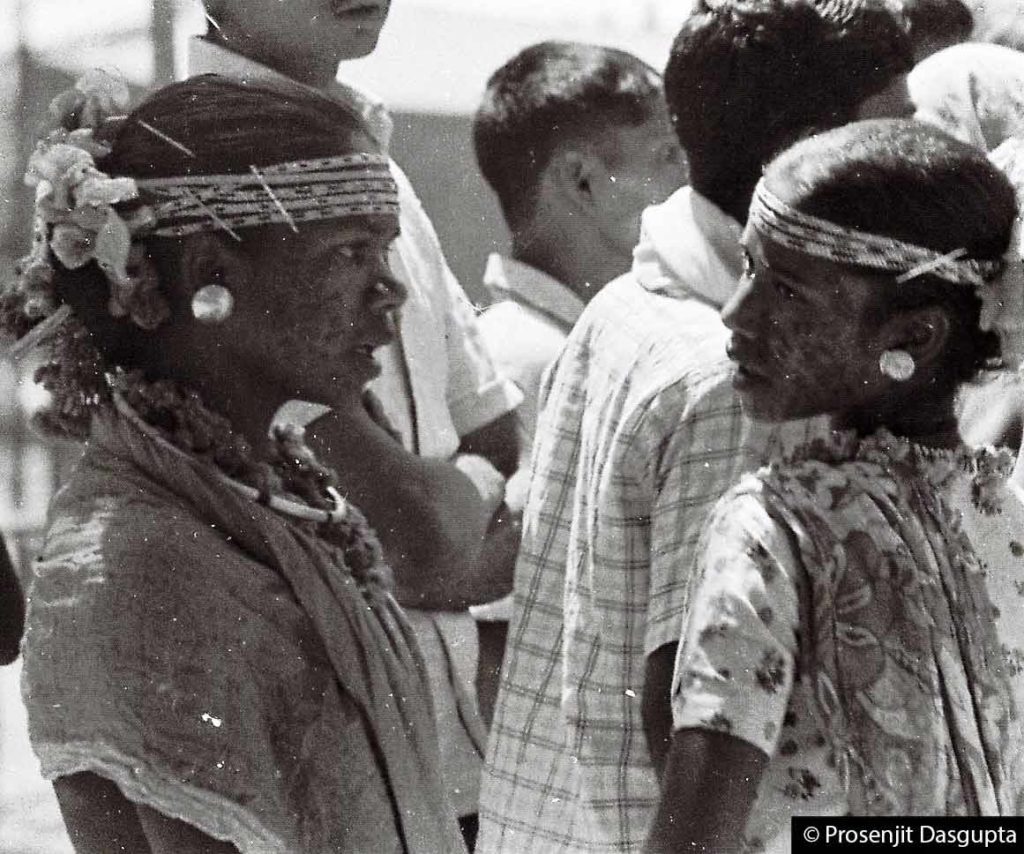

“Narainpur was all hustle and bustle because it was ‘haat’ or the weekly bazaar day. In those days, Narainpur was for all practical purposes a one-street town. The road came curving in from the east from Kondagaon and making a wide sweep, turned north towards Antagarh. Spread out under the huge mango trees next to the large timber yard, long lines of shops made a moving fair. The Muria chelik were there in good strength, swaggering about, arms around one another’s shoulders, throwing their heads back in laughter, their white teeth flashing, like so many children playing at being adults. Their dress was a tight white dhoti about the loins, as much for cover as for giving a firm support to the waist and hips for the long treks to and from the interior of the hills, an equally tight white turban with hair either tied in a knot or cut short at the nape of the neck, German silver bangles on the wrists, with beaded tassels fringing the pagdees (turbans), leaf cigarettes tucked in behind their ears or in the turban. The older men, feeling the weight of their liquor in the strong afternoon sun, growled softly amongst themselves. The Hill Maria looked their part as people of the hills, built more sturdily, with heavy hands, legs and feet, than the more lithe Muria, clad in nothing more than a loin-cloth” (from the book, “Chasing a Dream”).

“The night was pitch dark (‘marhai’ is usually held in the course of a dark fortnight, usually between the months of February and April), unrelieved by even a single electric light. Overhead the star-spangled sky hung over the surrounding hillocks and forests and a babble of voices rose over the small field that was to serve for the ‘marhai’ festivities……..The Muria were already getting ready for the ‘marhai’ dance by the flickering light of camp-fires. As we stood at the edge of the field, a large tableau rolled out before us – at the edge of the forest, the light of the small fires made the trees dance with the shifting flames, and lit up the small groups of chelik, here putting on their long petticoat-like dresses, or there tying tight the girdle of waistbells, setting their turbans and the ‘ jhal’ or a spike of the tail feathers of the Racket-tailed drongo and male red jungle fowl. The motiari looked frequently at a hand-held mirror in the insufficient light – just as any other debutant would do – meticulously tied the bead bands across their forehead and set and re-set the German silver hairpins or the carved wooden combs in their hair” (from the book “Chasing a Dream”).

And so it was, day after day and year after year, as impressions and experiences piled up one upon the other, almost smothering me. Sometimes, it was the big tribal dances of the “Marhai”, with the drums throbbing deep into the night, and chime of the waist-bells of the chelik rising and falling in waves. At times it was the dance of their god, “Anga”, and each village bringing in the larger family of the lesser gods and their siblings, Son Kuar and Lal Kuar, the large brass pots gleaming and the flags representing them fluttering in the wind. If the author, Nirad C. Chaudhuri, called India the “Continent of Circe”, Bastar was surely the district of dreams within it; it was magical.

About the Author

Born in Calcutta in 1944, Prosenjit Das Gupta completed his education from St. Xavier’s Collegiate School and Presidency College, Calcutta. He joined a commercial organization in 1966 and worked there, till his retirement a few years ago. His interest in wildlife and tribal and folk culture developed in his college days. He has travelled extensively, to tribal areas of central India as well as to national parks and sanctuaries. He has written a number of articles on wildlife and tribal culture and has authored several books on Calcutta, wildlife, common forest trees, his travels to tribal India, and economic change in India. He has also written a biography of Jim Corbett. His other interests include travelling, photography, reading and writing.

Buy his book on AMAZON “Chasing a Dream – Journeys into the heartland of Tribal India”

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi...

3 Comments on ““Bastar – Pictures from the Past I”, by Prosenjit Dasgupta”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This a link to a video, which shows how the Adivasi collect the sap of the palm tree : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTZDttyB_lk

Hi Dear Sipra,

Thanks for your kind message.

The principal ‘local beverage’ is indeed from Mahua flower.

Another common alcohol or beer is ‘Salphi’ created from the sap of palm tree.

Initially, the white liquid tends to be very sweet and non-alcoholic before it is fermented.

Palm sap begins fermenting immediately after collection, due to natural yeasts in the air (often spurred by residual yeast left in the collecting container). Within two hours, fermentation yields an aromatic wine of up to 4% alcohol content.

very interesting to know about the different tribes and their culture.would like to know more about the womwn and their costumes.Also what liquor did they drinkWas it from the mahua tree?