Durga-Puja, the divine festival of Kolkata

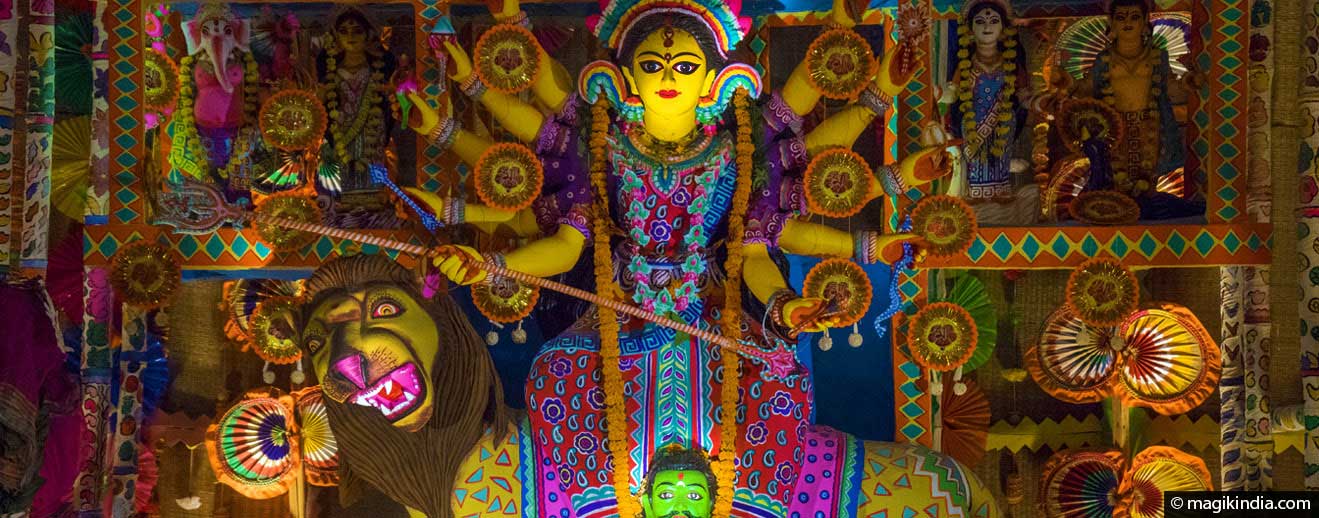

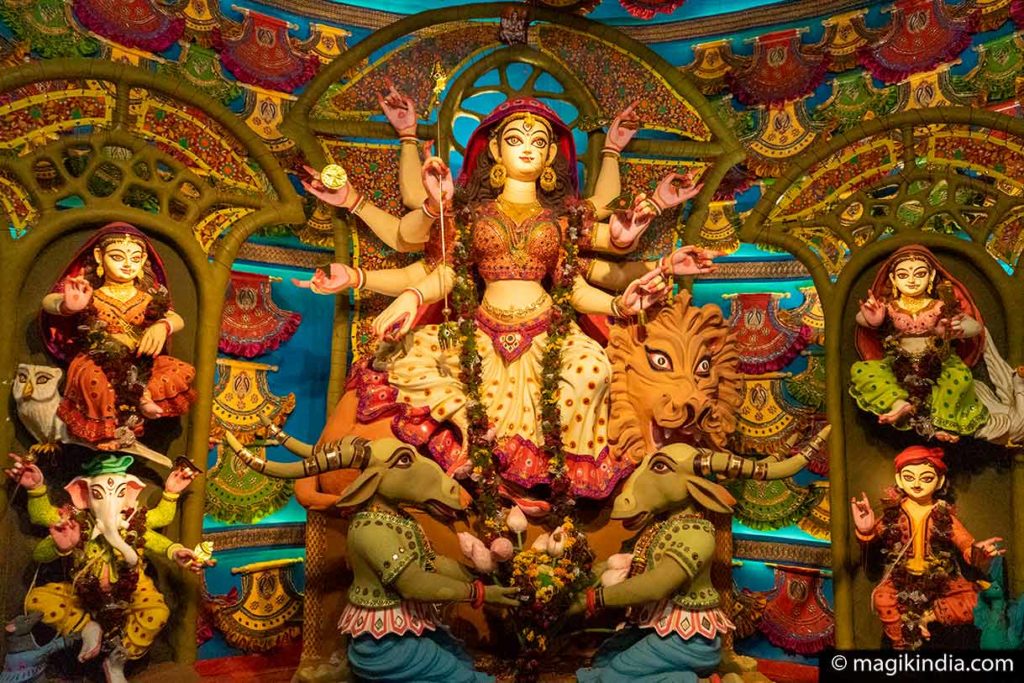

In West Bengal and its capital Kolkata, the great festival of Navaratri celebrating the Divine Mother is called Durga-Puja or Durgotsava (Durga Festival). It marks the victory of the goddess Durga over the demon Mahishasura. During the festival the city is up all night, decked in lights and embellished with temporary temples vying to be the most inventive and creative.

Durga-Puja is not only a religious festival; its social and cultural sides are important too. All social classes join in the celebrations. During the festivities Kolkata draws tourists from all over India and far beyond.

The Origin of Durga-Puja

As with most festivals in India, the origins of Durga Puja lie in Hindu mythology.

The demon king Mahishasura had become invincible because, thanks to a favour granted him by Lord Shiva, no male could defeat him.

To put an end to the terror he was causing, the gods pooled all their powers and gave birth to Shakti (the primordial force) in the form of the goddess Durga who, not being male, was able to defeat and kill Mahishasura. That is why Durga is also called Mahishasuramardini, “killer of Mahishasura”.

The battle symbolises the victory of good over evil and light over darkness.

Durga-Puja Highlights

The Durga-Puja festival lasts five days, called respectively Shashthi, Saptami, Ashtami, Navami and Dashami. The celebrations start on Shashti (the sixth day of Navaratri) and end on Dashami (the tenth day).

D 0 = Mahalaya – Durga comes to earth

D 1 = Navaratri starts (during 9 days)

D 6 = Shashti, Durga-Puja starts / 6th day of Navaratri

D 7 = Saptami, 2nd day of Durga-Puja / 7th day of Navaratri

D 8 = Ashtami, 3rd day of Durga-Puja / 8th day of Navaratri

D 9 = Navami, 4th day of Durga Puja / 9th day of Navaratri

D10 = Dashami, final day of Durga Puja / Vijayadhashami, Navaratri ends

According to Hindu mythology, the goddess Durga came to earth on Mahalaya (one day before Navaratri) to kill Mahishasura. Mahalaya marks the end of Pitru Paksha, the period dedicated to the ancestors, and the start of Devi Paksha, the period for worshipping the goddess. It is also said that the gods in the heavens stay awake throughout this period.

The clay statues of Durga have to be ready for the start of Devi Paksha; their eyes are painted in on the day of Mahalaya in a ritual called Chakshu Daan.

BODHON, BRINGING DURGA TO LIFE

On Shashti, the first day of the Durga Puja celebrations, a ceremony called Bodhon or Akaal Bodhan is held. It symbolically brings the Durga statue to life and marks the start of the festival.

The word akaal is made up of a (“not”) and kaal (“time”). Bodhan means “worship” or “invocation”. So Akaal Bodhan means to worship Durga outside the customary time.

The usual time for worshipping Durga, as laid down by the Hindu sacred scriptures, is in the month of Chaitra (March-April) and is called Basanti Durga Puja. But it is not much practiced and the September-October worship, called Sharadiya (autumn) Durga Puja is preferred.

The reason for celebrating Navaratri in autumn is that in Hindu mythology, it was autumn when Lord Rama prayed for Mother Durga’s blessing before the final battle against Ravana (see above).

[ Watch! Bodhon ceremony in Kolkata ]

BORON, FAREWELL TO DURGA

The festival ends on Dashami evening with the Boron (“welcome”) ceremony, a kind of farewell to Durga while praying to her to come back next year.

Married women in bright red saris and their finest gold jewellery come, preceded by dhaak drums and conch shell horns, to bid the goddess goodbye and beg her to come back next year.

They light oil lamps to light up her face, smear vermilion on her forehead as a wish for a long married life, feed her sweetmeats and clean her face with betel leaves.

When the last goodbyes are said, the women play sindur khela, smearing vermilion on each others’ foreheads and cheeks; it is a gesture of solidarity and bonding among married women and helps to integrate newly married women into their group.

VISARJAN, IMMERSION IN THE WATER

Then comes the moment of Visarjan when the deity is taken in procession and immersed in a river or other water body which, for the occasion, is considered the same as the holy water of the Ganges.

To the insistent beat of the percussion, the faithful dance along with the procession carrying dhunachi, earthenware lamps with coconut husk burning in them.

They shout “Bolo Durga mai-ki jai!” (“Glory to Mother Durga!”) or “Asche Bochor abar hobe!” (“It will begin again next year!”) and the statue of Durga, who just a few hours earlier was as splendid as only a goddess can be, humbly dissolves in the water. A beautiful symbol of the life cycle, dust returning to dust.

N.B: Because of India’s new anti-pollution laws, the idols are no longer left to disintegrate and float away with the current; they are just immersed for a few minutes and pulled out again. These new procedures rob the event of some of its charm but they are necessary in a country where most of the rivers are seriously polluted.

Statues and “Pandals”

Preparations for the festival start far in advance. In the months preceding the Durga Puja, clay idols of Durga are made and pandals (temporary temples) are built to house them. The pandals are funded mainly by local communities or business sponsors.

Making the statues is a long process requiring highly specific artistic craft skills. More than 500 artisans called pal work ardently to make tens of thousands of statues each year. They live in the Kumortali district of north Kolkata.

First they build a bamboo armature for the idol and the platform it will stand on. Traditionally, this process starts on the day of the Rath Yatra with a ritual called Puja Kathamo, kathamo being the Bengali name for the bamboo armature. Nowadays the process sometimes begins much earlier to meet the export demand for Durga statues.

Straw is tied around the bamboo with jute cords to form Durga’s figure. Then a first layer of clay is applied to the figure, filling in the gaps left by the straw. Additional layers of clay are applied with great care and skill to give the statue’s final, detailed form. The thickness of the clay is no more than 5 cm.

A high degree of skill is required to sculpt Durga’s head and face; this work is usually entrusted to the most skilled pals.

[ Watch! Durga statues workshop ]

The clay for the statues comes from the River Ganges. There is a surprising custom according to which it includes five or ten grams of earth, called punya mati, taken from the ground by a prostitute’s house.

The belief is that when someone enters the world of carnal sin they leave their purity and virtue behind; these are absorbed by the earth, so a little of this earth is gathered for building the Durga statue. This tradition comes from the Ramayana; in the Hindu epic Lord Rama himself uses earth from the house of a prostitute called Ambalika to create an idol of Durga.

It also takes time and effort to build the thousands of pandals or temporary temples that house the Durga idols in Kolkata. They are built on a precise plan and are made of bamboo poles, wooden planks and fabric. The tendency these days is to bring in an artist to design the pandal. These temples are fully-fledged artworks and it is understandable that eager visitors will queue for hours to admire them.