Pithora, the art ritual of Rathwa people

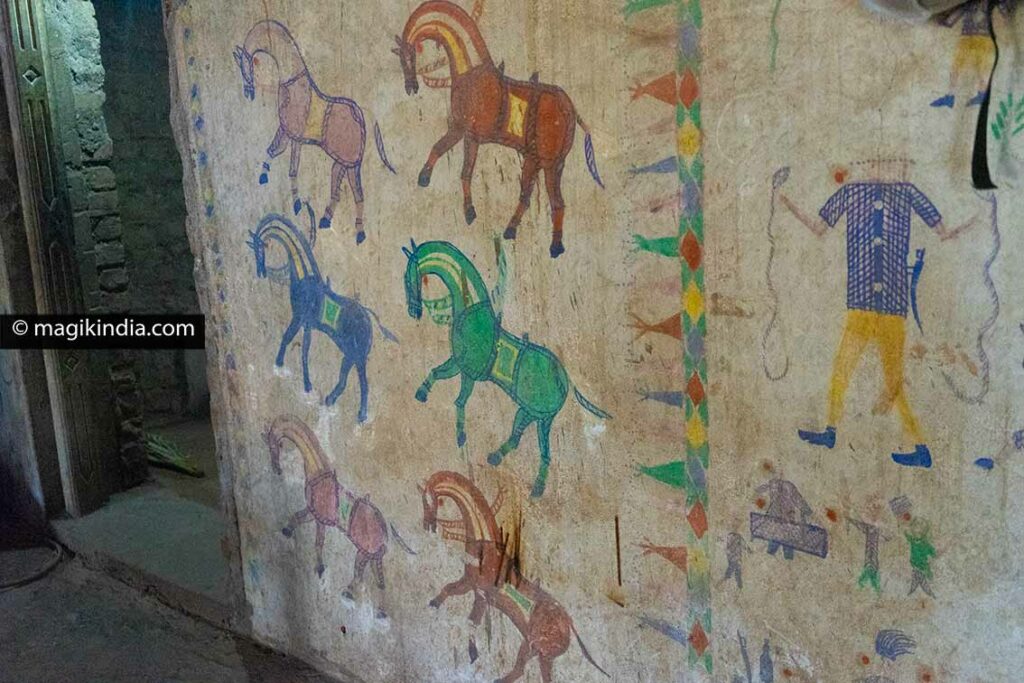

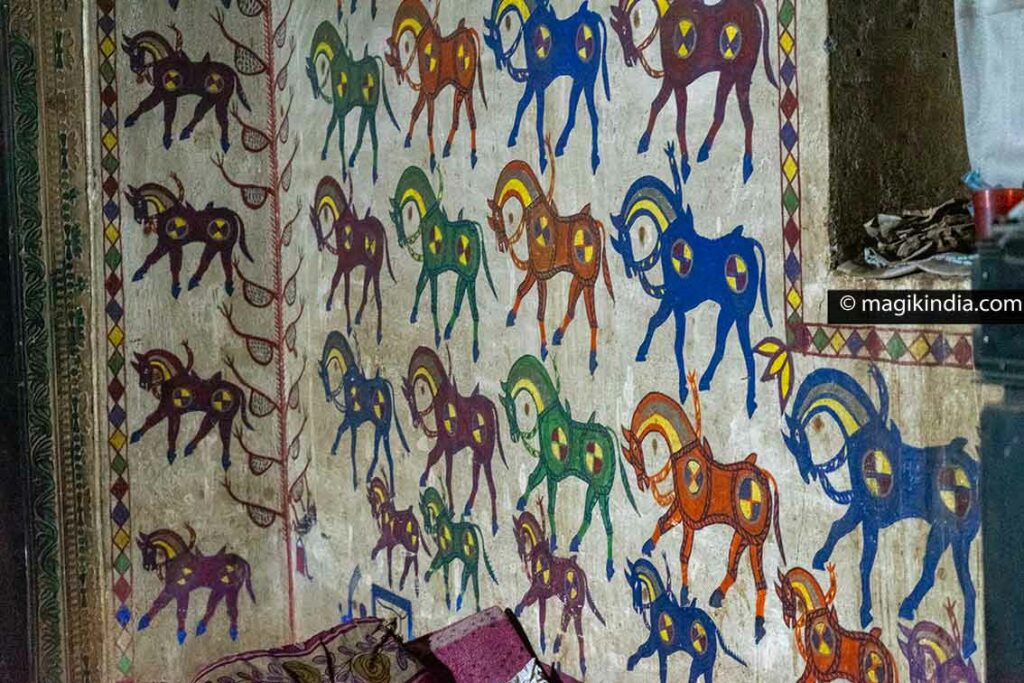

A Pithora painting, even reproduced on a canvas, is above all considered a sacred ritual. It is performed by the Adivasi Rathwa people of Chhota Udepur and Panchmahal districts in Gujarat. These colorful naive frescoes that seem to belong to millennial times, illustrate the mythology and the daily life of the Rathwas.

Pithoro, the main Rathwa deity

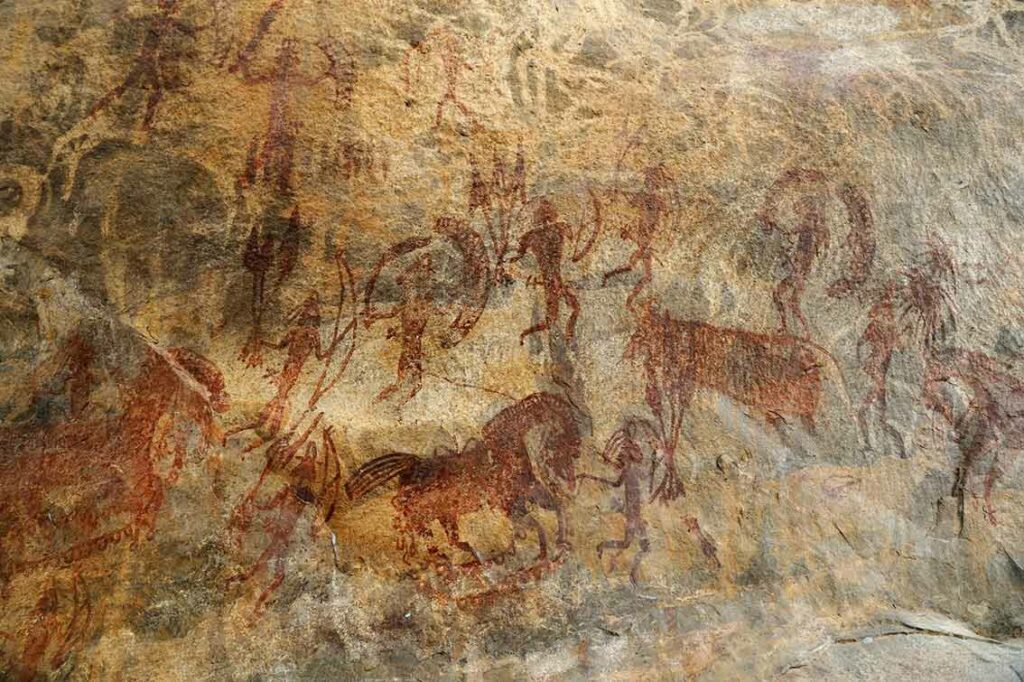

There are still many uncertainties about the origin of the pithora ritual art and the influences it may have absorbed. Some historians trace them back to prehistoric cave paintings with an assimilation into the Rathwa cosmogony of certain deities of the Hindu pantheon (the gods Indra or Ganesha, for example).

Pithora paintings mainly revolve around the story of the god Rathwa “Pithoro” or “Baba Pithoro”, after whom this art-ritual is named.

The story goes that Pithoro is the illegitimate child of Kali Koyal and King Kunjul (Kundu Rano). Kali Koyal is one of the seven sisters of the god Indra* (Baba Ind). In order not to incur the wrath of his brother, Kali Koyal laid the newborn baby in a lotus on the Yamuna River. He was miraculously taken in by his own sister Kajal who raised him like her own child. When Pithoro was of marriageable age, he wanted to find his biological parents. When his identity was revealed and Baba Ind recognized his nephew, he arranged a wedding with great fanfare and invited all the gods and goddesses.

*Baba Ind is the god of rain and protector of animals in Rathwa cosmology

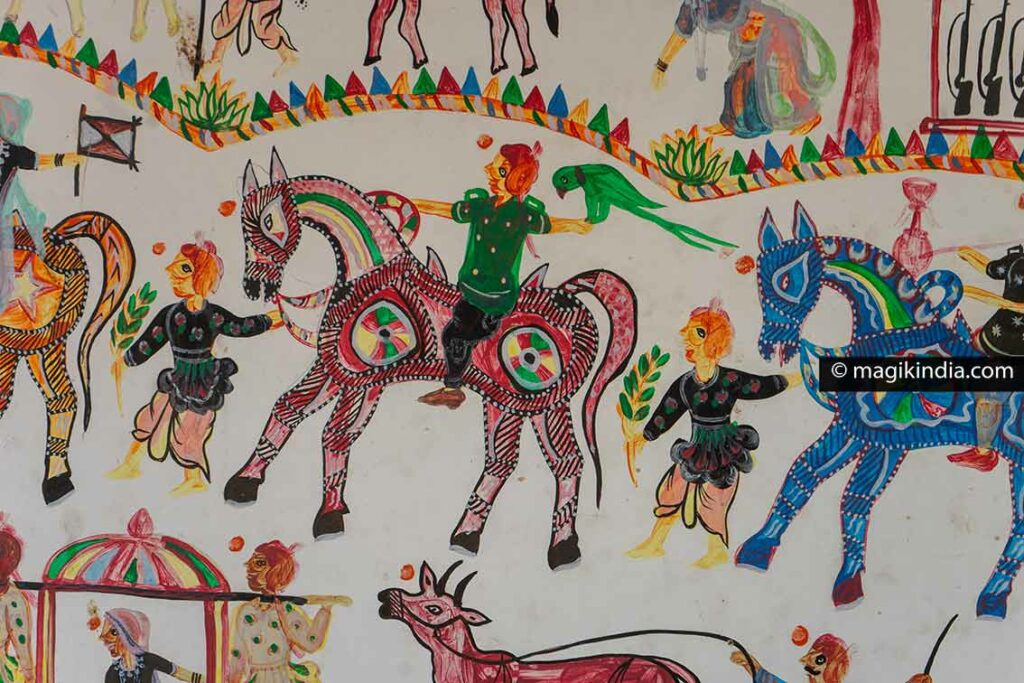

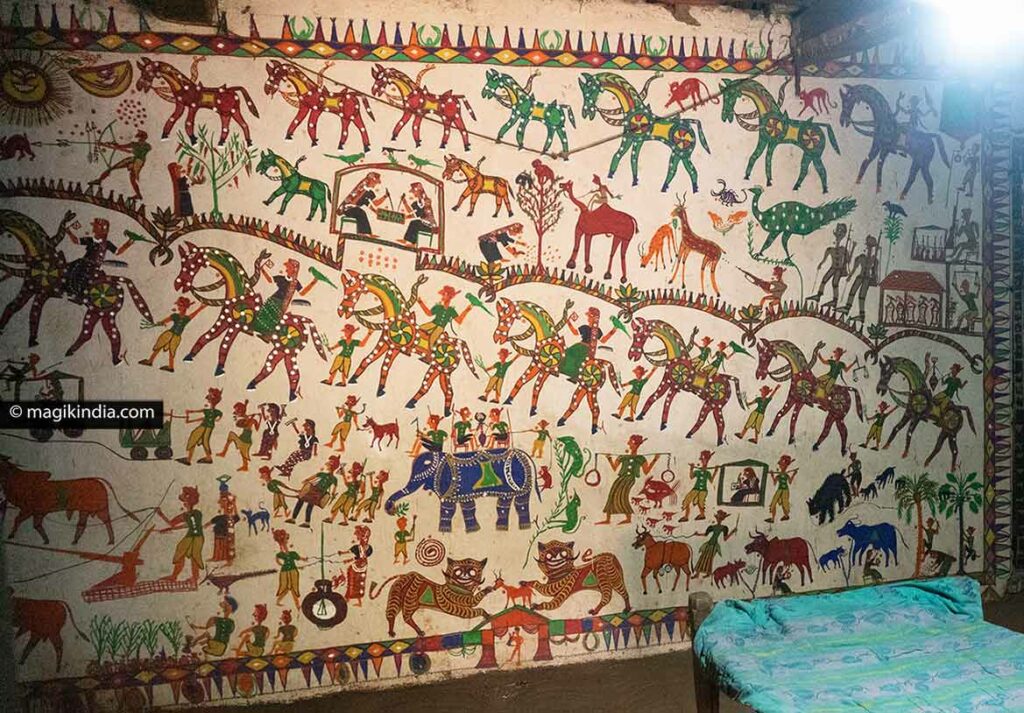

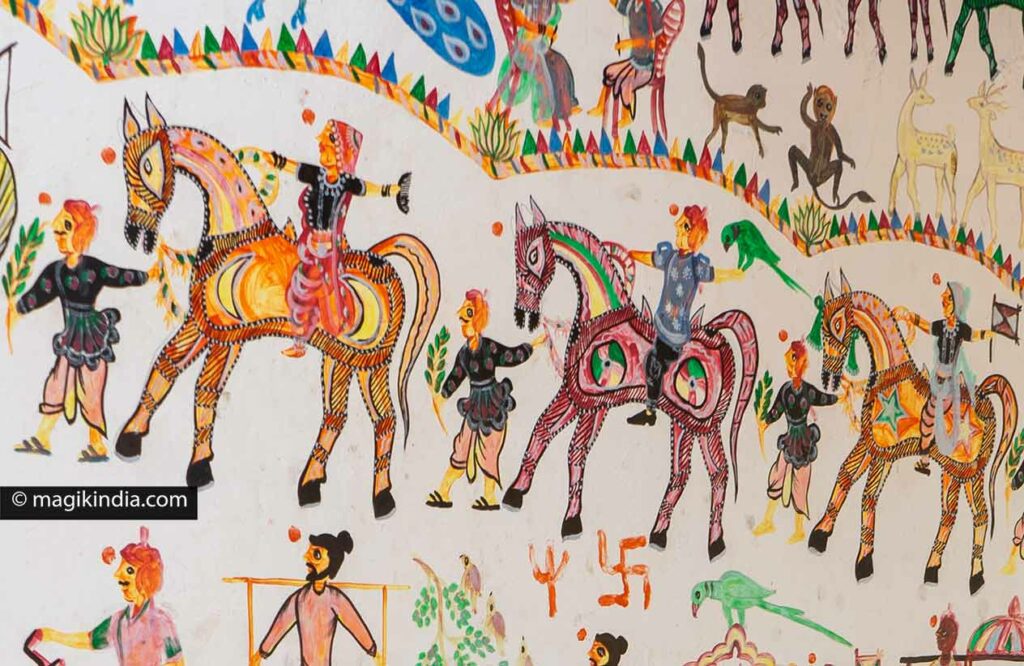

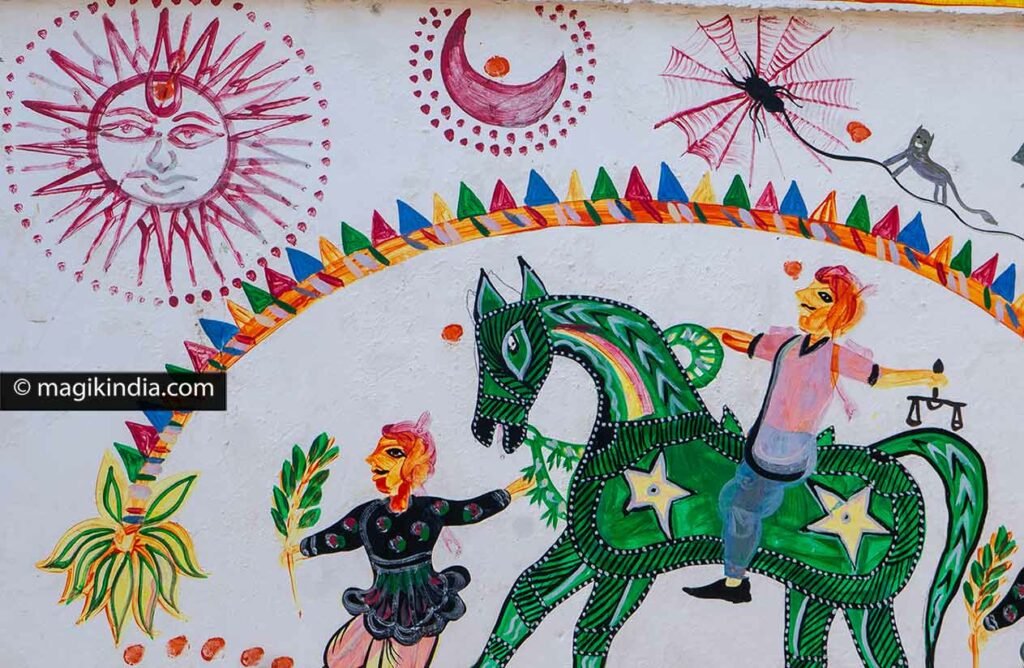

It is this wedding procession that is painted in the center of the fresco.

We see Pithoro on his horse holding a parakeet in his left hand and his queen “Pithori”, just behind with a fan in his hand. For the Rathwas, Baba Pithoro symbolizes all the creations of the universe.

Pithori is the daughter of Abho Kunbi and Mathari, the farming couple seen at the bottom of the painting. According to Rathwa mythology, they are the creators of agriculture and farming activities. Pithori is worshiped in times of drought.

In the procession, we also see Rani Kajal, Pithoro’s adoptive mother, holding a comb in her left hand. She stands in front of Pithoro, showing the importance of this goddess. She is, indeed, venerated as a “Kuldevi” or tutelary goddess by the Rathwas.

The god Baba Ganesh is the last in the procession, often painted blue and holding a “Houkah”, a hookah.

The process of a Pithora painting

The pithora is ordered by the “ghardhanis”, literally the owners of the house, as a sign of gratitude to Pithoro, after a wish has been fulfilled.

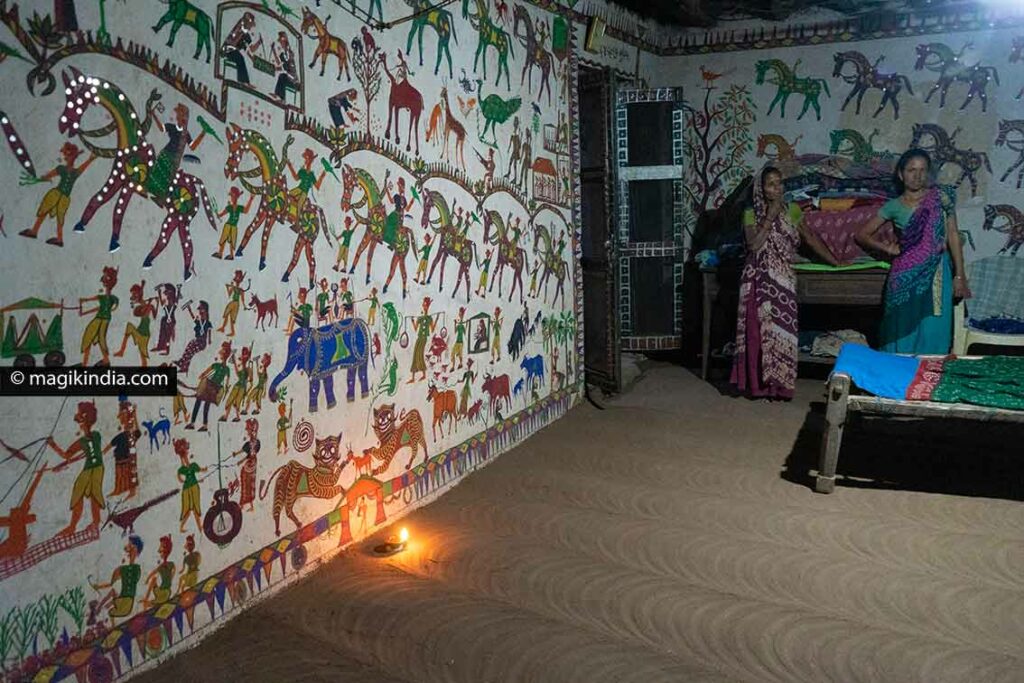

The painting is done on the three sides of the “Raj bhit”, the royal wall. It is usually in a room with a veranda that opens onto the kitchen.

The legend says that, in his childhood, Pithoro hid in this wall and chose it as his seat; it is on this same wall that the two sisters Lakhari and Jokhari (see below) wrote the future of the young god.

The three sections of the wall are covered with a first layer made up of dung mixed with earth and then with a second layer based on white clay (pandu). Traditionally, this coating is applied by the unmarried women of the household, called “Pandhuda Lavu”.

The Pithora process is then entirely orchestrated by the “badwa”, a sort of shaman. The family contacts him when they wish to initiate the ritual painting. Once the badwa sets the auspicious date, the “lakharas”, the painters (men only), are invited.

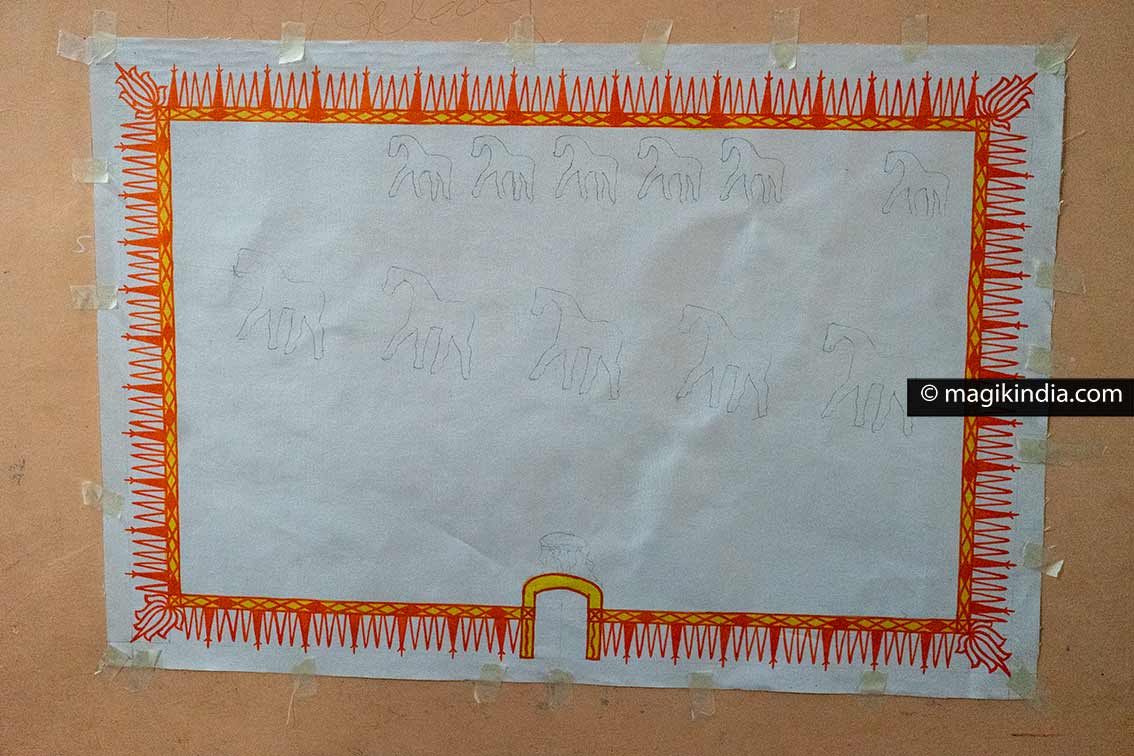

The lakharas first draw the “heem”, a border made up of triangular geometric patterns, with a round entrance known as the “jhanpo”. The four corners are meant to represent the four ends of the earth.

The painters then draw the horses, recurring motifs of the Pithora, then the gods and goddesses riding these horses and so on. Baba Ganeh with his “houkah” is the first deity to be painted.

Chants and incantations accompany the creation of the Pithora.

Traditionally the lakharas use bamboo stalks as brushes as well as natural pigments mixed with mahudo (alcohol made from the Mahua flowers) and cow’s milk for the different colors.

When the Pithora is completed, a goat is sacrificed in front of the “royal wall”. The Badwa priest, armed with a sword, then enters a trance and inspects the fresco. At this time, the Rathwas consider it to be the god Pithoro manifesting through his body. The Badwa then states the stories of the gods and makes predictions about the family. If the fresco has flaws or elements are missing, he points them with his sword. The lakharas will then have to make the necessary corrections.

This final ritual somehow gives life to the fresco; she will now be seen as a member of the family. At each special event, festival or rites of passage, offerings will be presented to Baba Pithoro.

The different representations of the Pithora

It’s rather Difficult to give an exhaustive explanation of the different elements represented on a Pithora, because there are more than a hundred of them and they can change according to the lakharas, each one having its own artistic signature. I would therefore describe to the main representations.

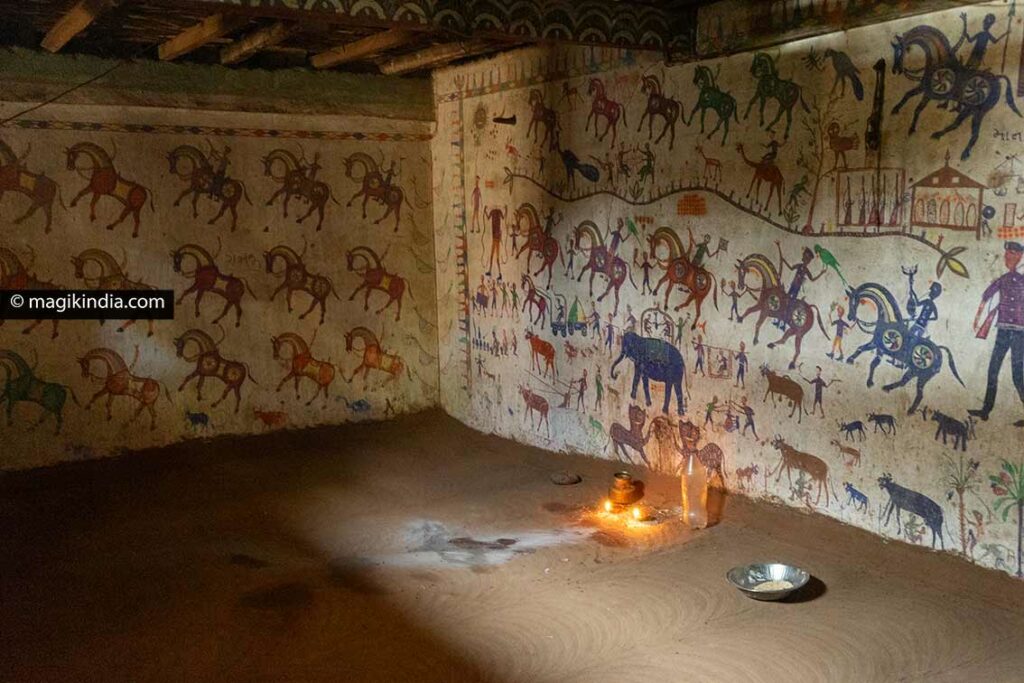

The main section, which opens onto the kitchen is divided into three horizontal parts: the “celestial” part, the wedding procession and the section linked to the earth.

The upper part somehow represents the world of the gods. Sun-god (Huriya dev) and moon-goddess (Handaryo Dev) are painted in the left corner. They are the universal guardians of the earth.

Just beside or below, a curious drawing shows a tiger clinging to a spider’s web. The spider is “Mamo Karodiyo” Baba Pithoro’s maternal uncle. Using his web, he once helped Pithoro join Baba Ind in the realm of the gods.

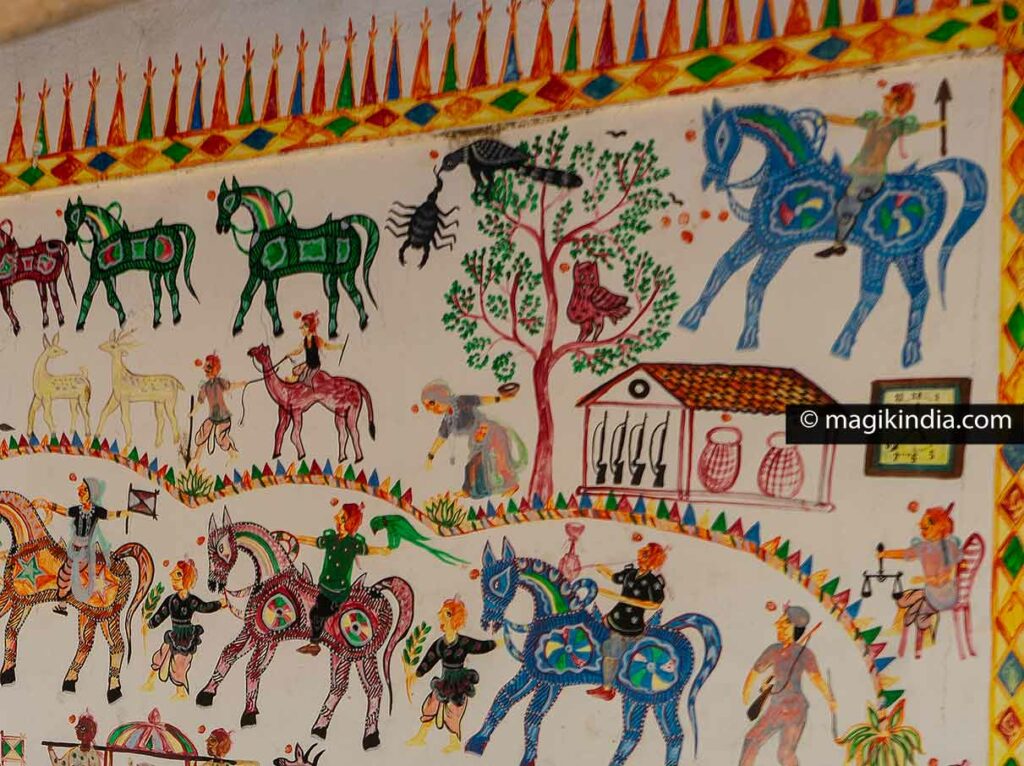

On this same part of the fresco, in the upper right corner, we can see Hadhol on his blue horse who is a messenger of the gods.

We also see, in a tree, a black bird holding a scorpion in its beak. This bird is a Koyal, a cuckoo, whose song is part of the typical sounds of India. It represents the goddess Kali Koyal, the adoptive mother of Pithoro. I haven’t gotten the meaning of the scorpion yet, even from my lakhara friends… To be continued…

In this same tree is kikiyari, the messenger owl of solar and lunar eclipses.

In the center of the upper part of the fresco, two women are seated: they are the clairvoyant sisters Lakhari and Jokhari. They are the ones who wrote the future of the young god Pithoro on the wall.

Just next to the right, we can see the god of livestock, perched on his dromedary. Kaman, the god of hunting is represented with a bow.

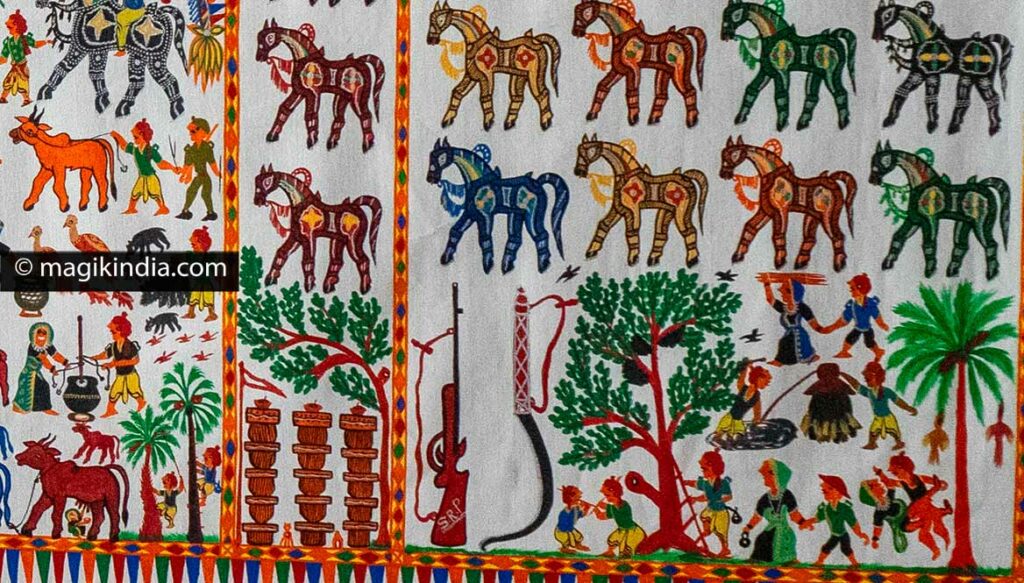

Between the top left and right corner of the fresco, five riderless horses (Purvaj na Panch Ghoda) are believed to represent the ancestors of the family.

The second section, in the center is that of the wedding procession of Pithoro as seen above. The wavy line above the horses would represent either a garland, a river or the symbolic border of the village.

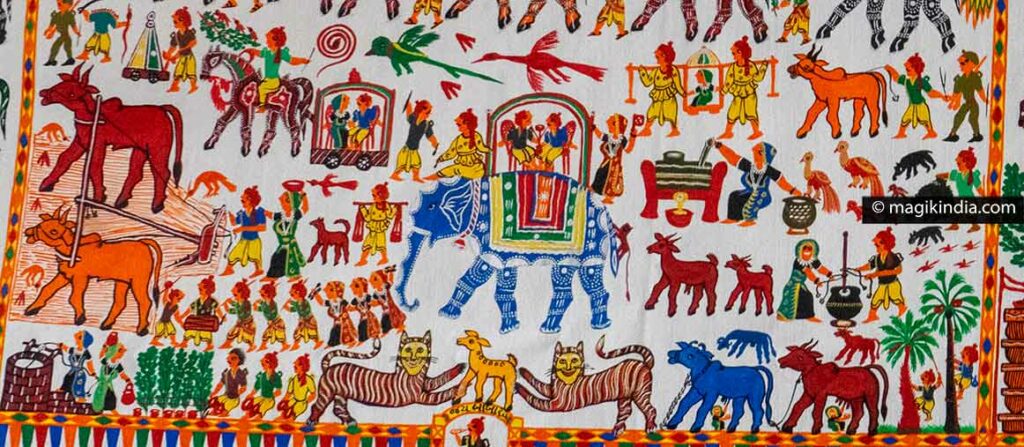

The third section of the pithora, below, is that related to the earth. It describes the daily life of the Rathwa who are originally farmers. We therefore see there, among other things, the work of the fields, the breeding, the hunting, the churning of butter, the collection of honey and of course the making of the Mahudo and Taadi, the alcoholic drinks of the Rathwas (which we also found among the adivasis of Bastar).

In this third part of the fresco, two other characters stand out: the “Raja Bhoj” on his blue elephant (in the center) and the “Baar Matha no Dhani”, a twelve-headed man.

Raja Bhoj was a great king who was very benevolent towards his subjects. He is always represented riding an elephant. Raja Bhoj takes care of agriculture and livestock.

Baar Matha no Dhani (literally “the 12-headed enlightened one”) is a curious character with indeed twelve heads who holds Nagdev (the lord of serpents) in his hands. Some scholars believe that there is a correlation here with Ravana of the Ramayana epic; for the Rathwas, it is an indigenous deity who protects them in the 12 directions. He possesses knowledge of the entire universe and protects all living organisms.

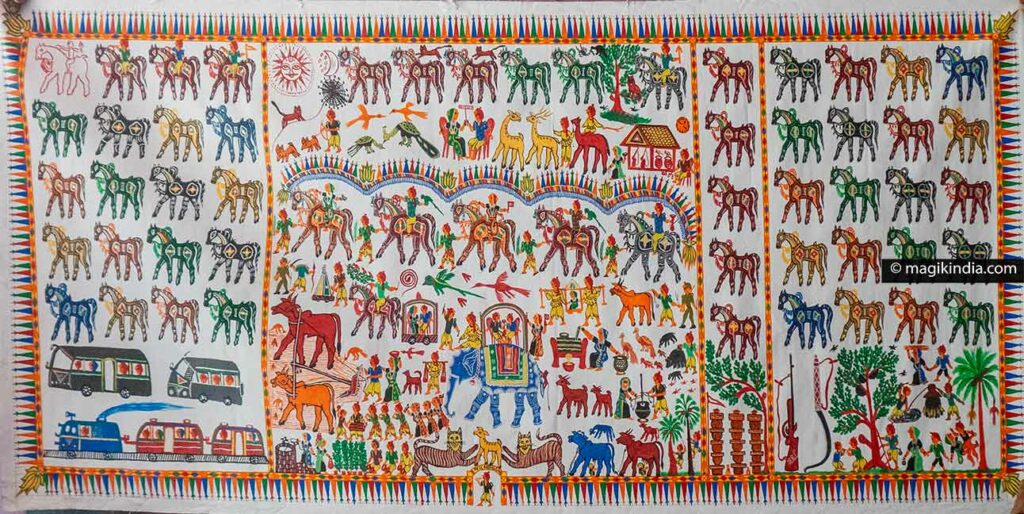

The two side walls are largely covered by horses representing the ancestors and brave warriors (Saval Dharmi Ghoda). Contemporary elements such as planes, cars, trains also find their place in this painting.

The extra-marital sexual act of Kali Koyal and King Kunjul is sometimes shown in one of the side sides of the painting.

Among the brave warriors is “Nakti Bhuten” who is depicted on a white or unpainted horse, placed in the top corner of the left side wall. He is the powerful protector of the house.

The Pithora in modern Indian society

There are now only a handful of lakharas left. Just as I mentioned for the Bhils and their Gavari folk theatre, traditional arts are slowly being lost in India. The younger generation has little economic motivation to take up the torch and often migrates to big cities.

There are indeed a few measures put in place by the government, such as the classification, for example, of Pithora art as a protected geographical indication since 2021. It will surely take other initiatives to save this ritual art and, above all, a strong will of the Rathwa people themselves.

The Rathwa family that I met during this report is an exception, they have been lakharas from father to son for five generations. The junior lakhara, Naran Bhai, has been invited to several international fairs to promote the Pithora which he paints on canvas. Perhaps this is a way to save this art, no offense to purists who wish to keep this art on the walls only.

if you wish to promote this art-ritual and order a Pithora canvas painted by this Rathwa family, please contact me.