Dungarpur, the hidden pearl of southern Rajasthan

Dungarpur, located in the very south of Rajasthan, is a small city often forgotten by tourist circuits and one wonders why, for its “Juna Mahal”, although worn by time, offers exuberant interiors that have nothing to envy to the most beautiful palaces of the land of kings. In addition to its historical monuments, the city of the Rajputs Guhilot, nestled between the Aravalli mountains, benefits from a particularly green environment inhabited mainly by the Adivasi Bhil community who, long before the Maharawals, governed the region.

It is said that the city of Dungarpur takes its name from Dungaria, a powerful Bhil chief (one of the tribes of India) who reigned over this district. Its territory was however coveted by the Rajput ruler Veer Singh Dev who owned the county near the present city of Dungarpur. In 1258 CE, he conspired with a Dungarpur merchant and had him murdered. To assert his power, he built a fortified palace, the Juna Mahal (see below) on the foothills of one of the neighboring hills.

Dungarpur is also translated as “dungar na gharan”, “the house on the hills” because of its natural surroundings. It was the seat of the elder branch of the Sisodia of Udaipur, a Rajput clan of the Suryavanshi (solar) lineage which reigned over the kingdom of Mewar (Rajasthan).

After Veer Singh Dev, 32 kings (the “Maharawals”) succeeded one another in Dungarpur, until 1948 when the city was incorporated into the state of Rajasthan. The current honorary Maharawal (the 34th) is Shri Mahipal Singh II Bahadur.

And now, let’s visit Dungarpur !

Juna Mahal (old palace)

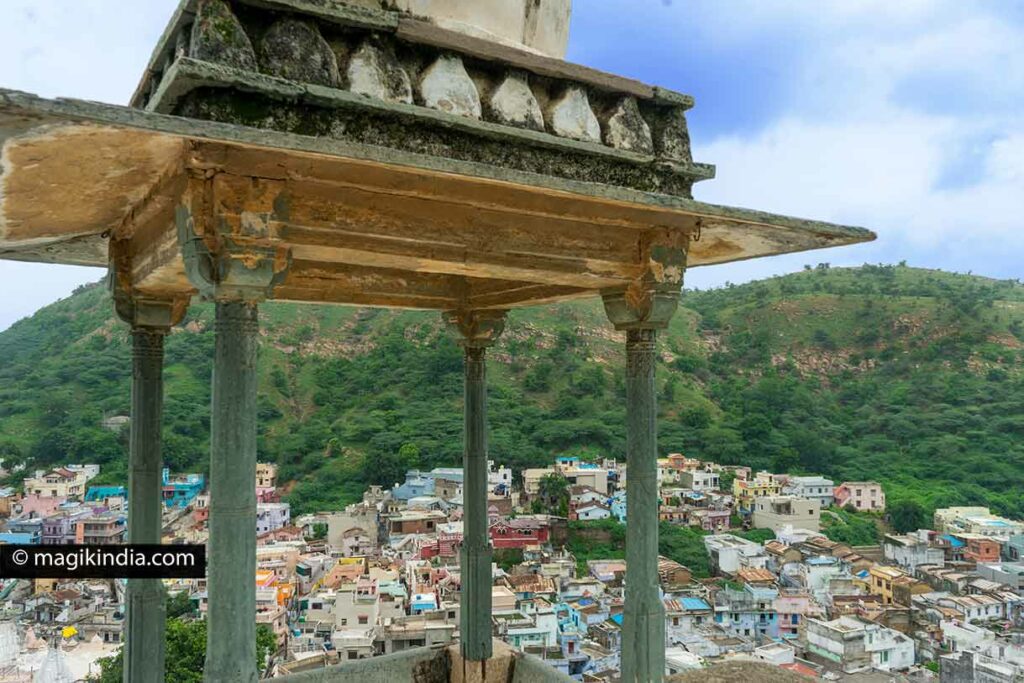

Overlooking Dungarpur, the seven-storey old palace was designed as a citadel, with watchtowers, ramparts and fortified walls.

Maharawal Veer Singh, the founder of Dungarpur, who was looking for a place in height to parry the possible attacks of his enemies, built a first structure of two floors. His successors will add their personal touch during each of their reigns.

We reach the Juna Mahal through the maze of the old city ; the place seems almost abandoned. We have to make sure it’s the Juna Mahal by asking local residents who quietly sip their chai under a tree.

At this precise moment, given the exterior condition of the building, I wonder if it was really worth a visit and am curious to see what’s in store for me. I will not be disappointed!

From the courtyard of the elephants (there were two of them in the time of Udai Singh II), we take a cramped corridor then a flight of steps leads us to a small rectangular courtyard, the Jambua Chowk, in the middle of which a beautiful tree grows.

The western part of the palace (on the left in the image above) has different floors, decorated with colonnaded verandas. Small originality, the stone wall covered with moss on the left of the courtyard, presents frescoes carved in the granite of dancers and elephants which seem to emerge from the wall.

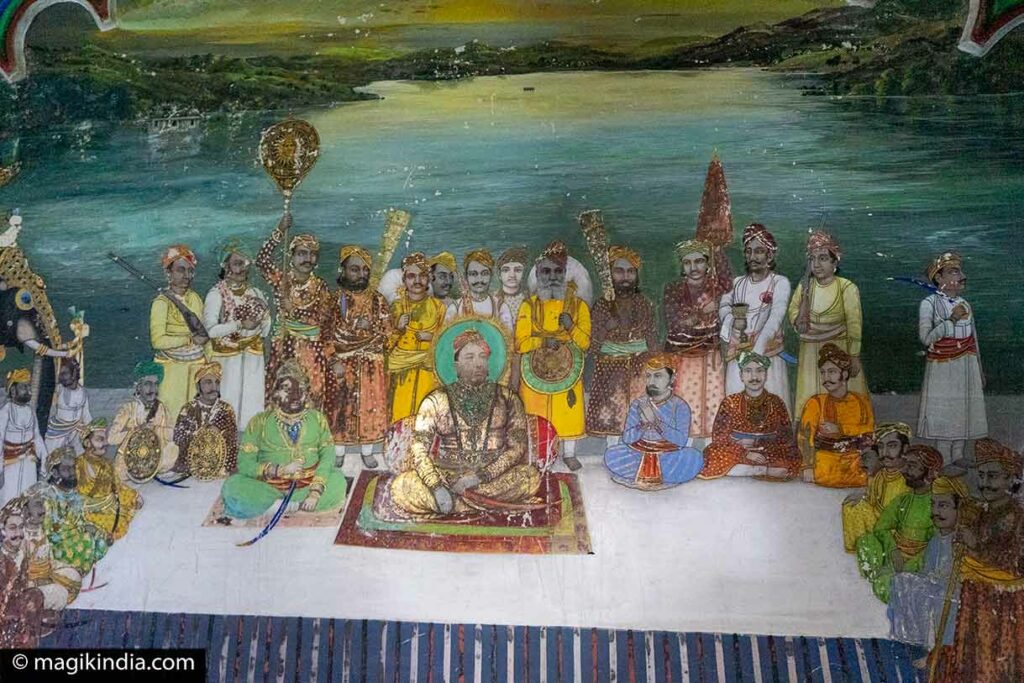

Several rooms are distributed all around the courtyard, rather sober in appearance. The Durbar hall, the royal reception hall, stands out. Designed by Maharawal Veer Shiv Singh, it was then used, at the end of the 19th century, by Udai Singh II as a personal office and, until 1940, by Lakshman Singh as a magistrature’s hall.

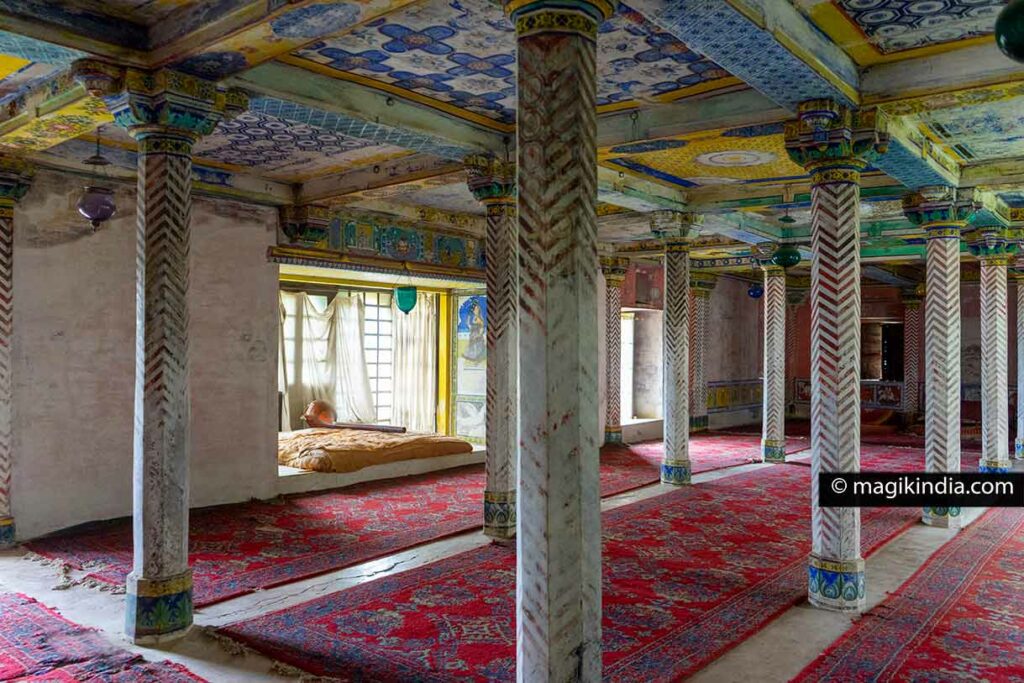

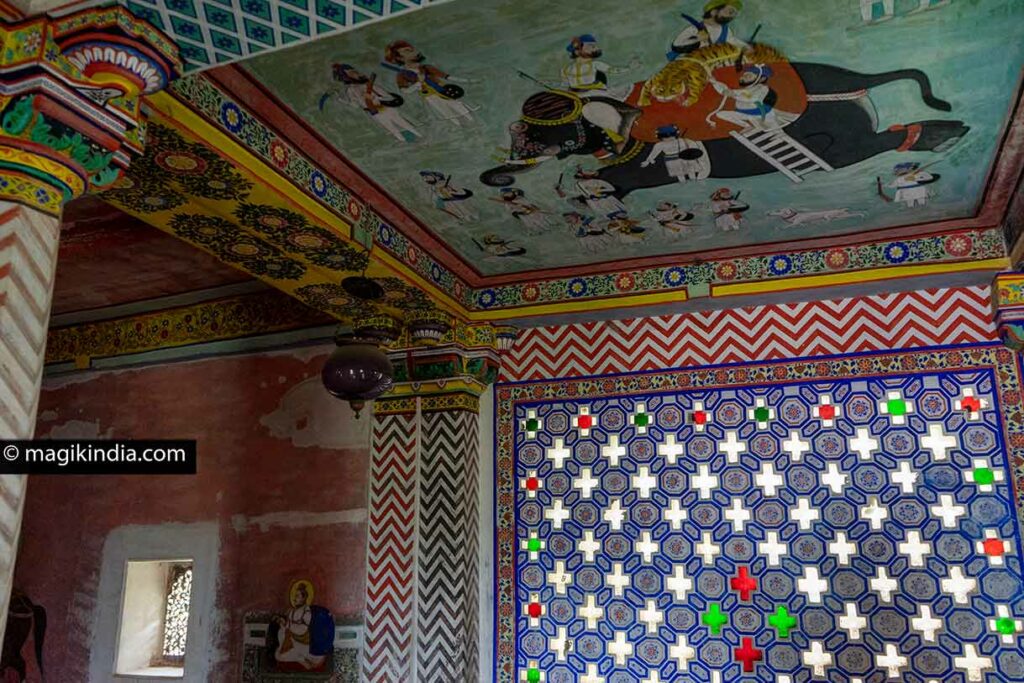

The room, held up by a dozen pillars adorned with herringbone patterns, is not well maintained and the set of cushions (the throne) at the back of the hall are dusty, however the refined frescoes and the wall panels inlaid with cross-polished glass anesthetize my first bad impression.

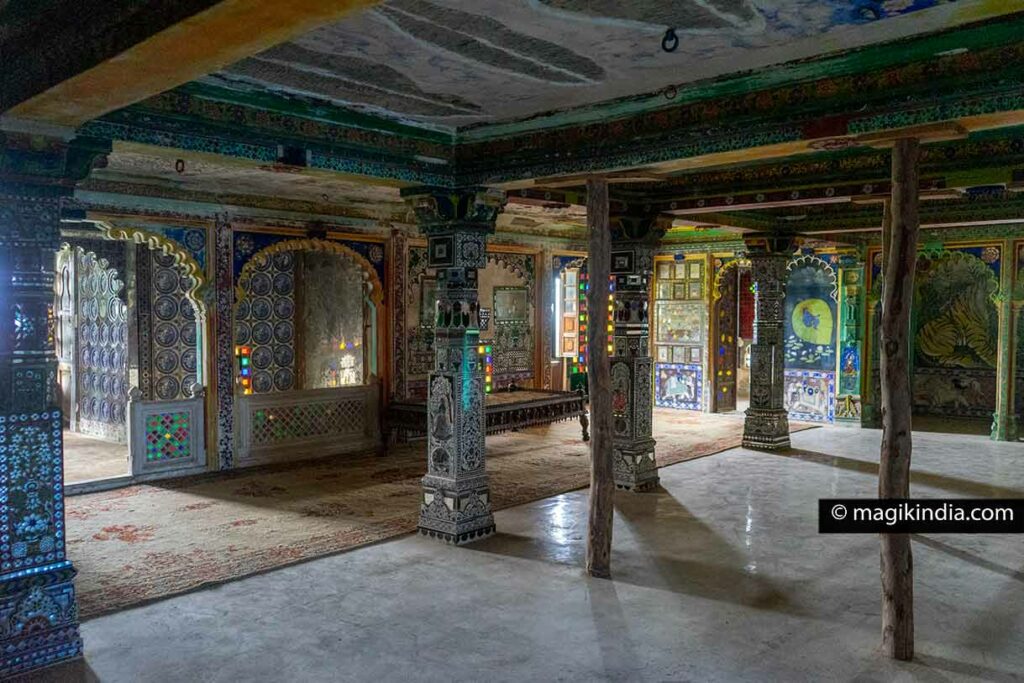

After the Tosha Khana on the 1st floor (office of the Prime Minister in 1300) which, if not historical, is of little interest, we climb another floor and arrive in what is surely the most beautiful part of the Mahal: the Aam Khas.

It is a large pillared space that impresses with its decorative exuberance; it was used as an audience hall (Diwan-e-khas) to entertain illustrious guests.

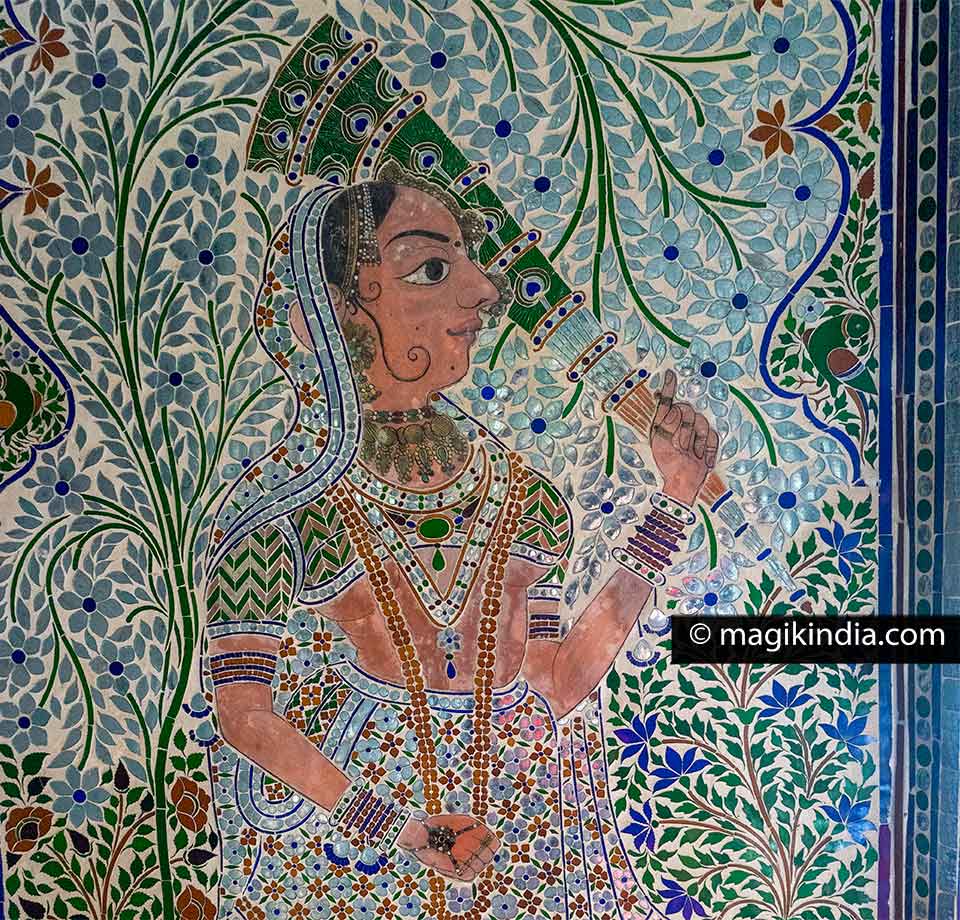

The Aam Khan was created in the 18th century when Rawal Shiv Singh built an additional floor on the west wing of the palace which he called Shiv Mandir. A century later, Udai Singh II renamed it “Udai Prakash” and added murals, mosaics of mirrors and colored glass and inlays of Chinese porcelain.

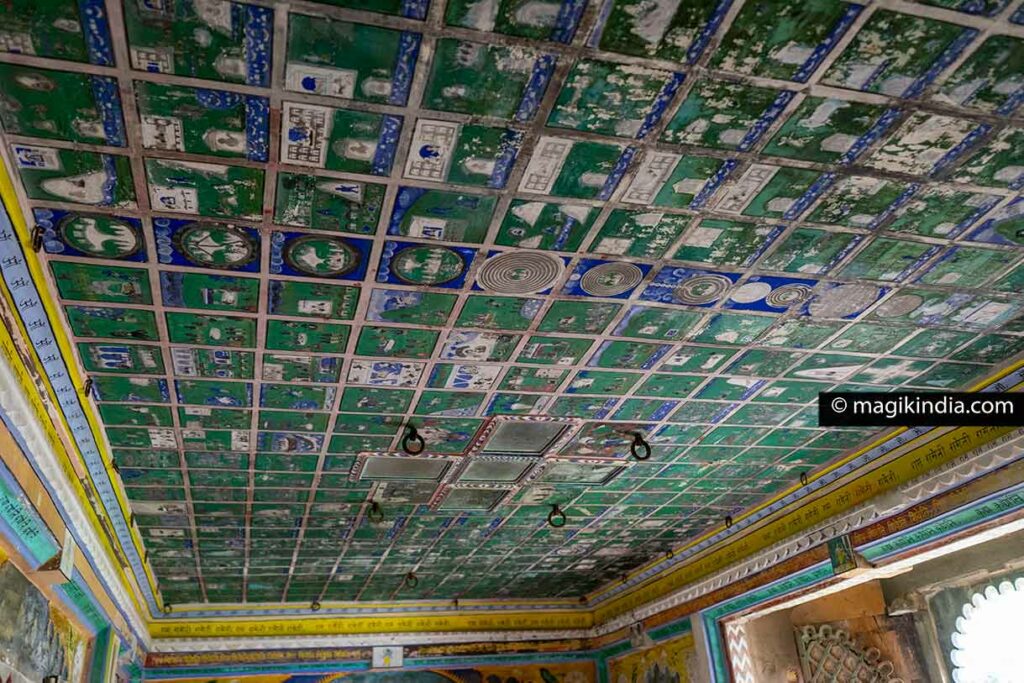

Opposite the entrance on the right, there are two small rooms that were once used for pujas, Hindu rituals. They are decorated with characters from the Indian epic Ramayana and the life of Lord Krishna. Remarkably, the ceiling of the first room tells the entire story of Mahabaratha, the other Indian epic.

Apart from these two rooms, there is also, around the large audience hall, a bathroom and a sumptuous room encrusted with mosaics of mirrors and glass where the Maharawals and their guests appear, elegant women as well as courtesans.

On another side of the room, you can also see a wall decorated with Chinese porcelain plates, another of the eclectic aspects of this palace which combines several influences.

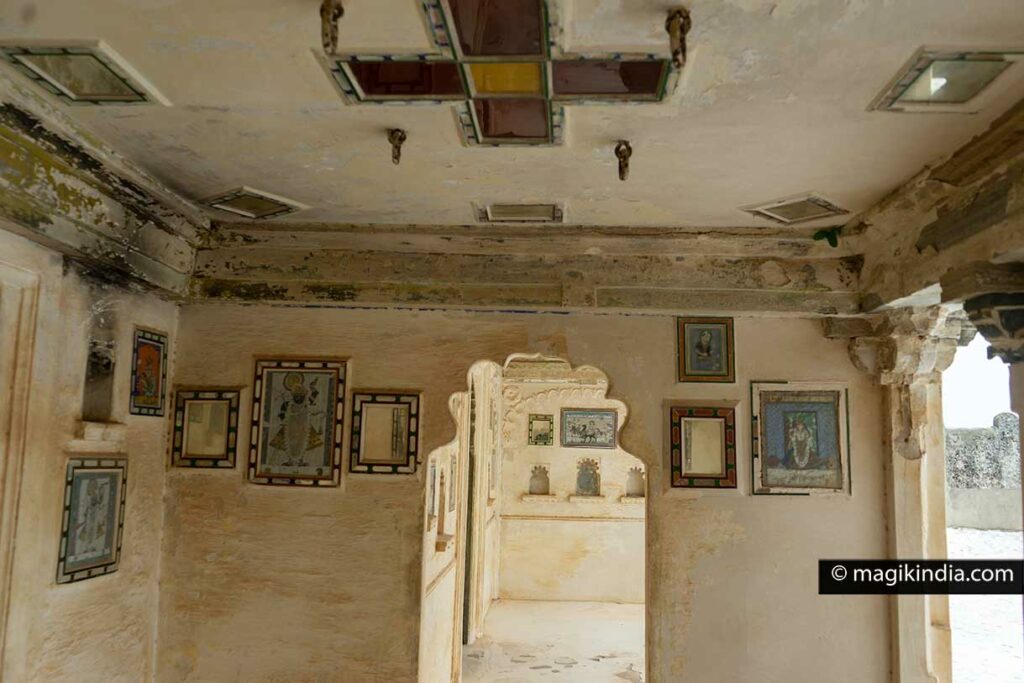

We climb another floor and arrive at the “Jali Ka Mahal” (the palace with the jalis), the part reserved for the women of the court.

A “jali” designates an openwork panel generally with ornamental motifs, typical of Indo-Islamic architecture; it lets light and air through while minimizing the impact of sun and rain. Also, as air passes through these small openings, its velocity increases, resulting in deep diffusion. It also allows you to see without being seen; the Rajput women, in fact, did not show themselves and when they had to appear in public, they covered their faces (purdah); this is still the case today in some traditional places of Rajasthan.

In the middle of the Jali ka Mahal, is the “Raniji ka Kamara” (the queen’s room) which, contrary to what its name may indicate, was reserved for the concubine Suraj Bai of King Udai Singh II who reigned in the 19th century .

This part consists of a room with a bathroom whose floor was polished like a mirror with “ghotmakali”, a lime-based coating. The room has pretty frescoes, one depicting in particular a procession of Gangaur, one of the flagship festivals of Rajasthan.

The top floor has another important room: the Karni Gokhda; from there, the king addressed the court from a balcony. It includes three rooms decorated with sublime frescoes of Hindu mythology, the life of the lord in particular and some scenes from the daily life of the Maharajas.

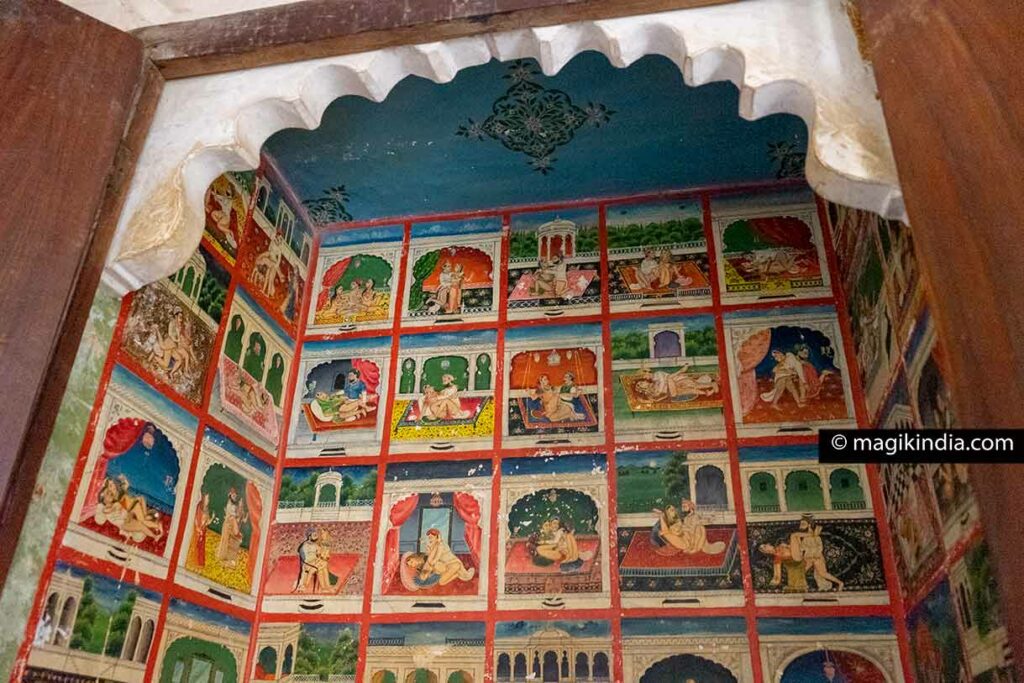

At the back the first room a descriptive panel, which I had not seen during my first tour, displays an evocative title: “Kamasutra”. As I had observed none of these famous representations of “the art of love” among the frescoes of the three bedrooms, I did a second round to check, in vain. Seeing me whirling around in search of that sensual “Grail,” the palace guide finally opened two doors of what appeared to be a closet. Inside, in an alcove, 54 Kamasutra positions (yes, I counted!) are delicately painted in bright colors.

This erotic decor was created at the request of Maharawal Shiv Singh at the end of the 18th century to “embellish” (this is what is written on the description) a niche that had remained empty. Four generations later, his descendant Bijay Singh (1898-1918) put a wooden door in front of these frescoes to hide them from the puritan eyes of the time.

The small outdoor courtyard of the Karni Gokhda has a narrow staircase by which we access a terrace which offers us a panoramic view of Dungarpur and the ancient city walls.

N.B.: tickets for the Juna Mahal (250 rupees in 2021) must be taken at the Udai Bilas Palace, it is indeed a private residence of the royal family of Dungarpur.

Udai Bilas, the new palace-hotel

Set on the shores of Lake Gaibsagar, Udai Bilas is the current residence of the Royal Family of Dungarpur. A part is dedicated to them, another has been converted into a 5* hotel. If you are not residing at the hotel, the visit to the palace is at the discretion of the venue manager.

The history of Udai Bilas Palace dates back to the middle of the 19th century, when Maharawal Udai Singh II, a great lover of art and architecture, designed this place in pareva stone (a local granite in gray-blue tones) in combining Mughal and Rajput architectural styles.

Opposite the palace, a small island on the lake is home to the royal family’s Bijayrajrajeshwar temple dedicated to the divine couple Shiva and Parvati. The Rajput style construction was started by Maharawal Vijay Singh but its official consecration was done in 1923 by Maharawal Lakshman Singh. The hotel organizes a temple tour for hotel residents only.

The centerpiece of the place is, for me, the impressive ornamental tower that rises in the middle of the palace’s main courtyard. It has four floors decorated with humpback arches and friezes carved in pareva and white marble. The room on the top floor is said to be embellished with semi-precious stones.

The second little gem of the palace is its open-air dining room located in the old Zenana (part reserved for women). There, in the middle of the room, stretches a long white marble table encrusted with colorful patterns with, as a table runner, a trickle of water where floating candles gracefully illuminate the evenings. On the walls of the room, black and white marble pebbles have been placed in a frieze, adding to the originality of the place.

Next door, the banquet room also serves as a dining room with a long wooden table. The parquet is original as well as the wallpaper. This hall has hosted various personalities from all over the world and members of various royal families in India.

The rooms of the palace are all different and have been deliberately left in their original state with period furniture which is not without charm, but can also make it look a bit outdated.

On the other side of the palace is the “Dungarpur Mews”, the motor stable, built by Maharawal Bijai Singh between 1910 and 1914. It was first used for his horses, then it was extended to make a huge garage that can accommodate about forty cars.

At present, there are splendid collector cars on display, among them a 1939 fiat 7-seater saloon, a Jaguar XJS and Mercedes 380SL and 320 SL. Also on display are cannons, an old 1910 steam roller from Marshall & Sons and a scale model of the Airco DH.5, a British single-seat fighter biplane from the First World War.

The surprise of the place is its bar, at the very end of the garage, which you reach by sneaking between the vintage cars, it is full of automotive memorabilia of all kinds. Guaranteed atmosphere.

Udai Bilas also has a private museum (ajaibghar) of the Maharani Manhar Kumari which includes, among other things, an eclectic collection of textiles, miniature paintings and ceramics.

Other visits in Dungarpur

Srinathji temple

Set on the shores of Lake Gaib Sagar, Srinathji (Krishna) is a beautiful Hindu temple built by Maharawal Punjraj in 1623. The main shrine houses human-sized statues of Goverdhannathji and Shri Radhikaji. It also includes 52 other small temples. Be sure to climb the steps to the Hanuman Temple which offers stunning views of the city and the lake.

Badal Mahal

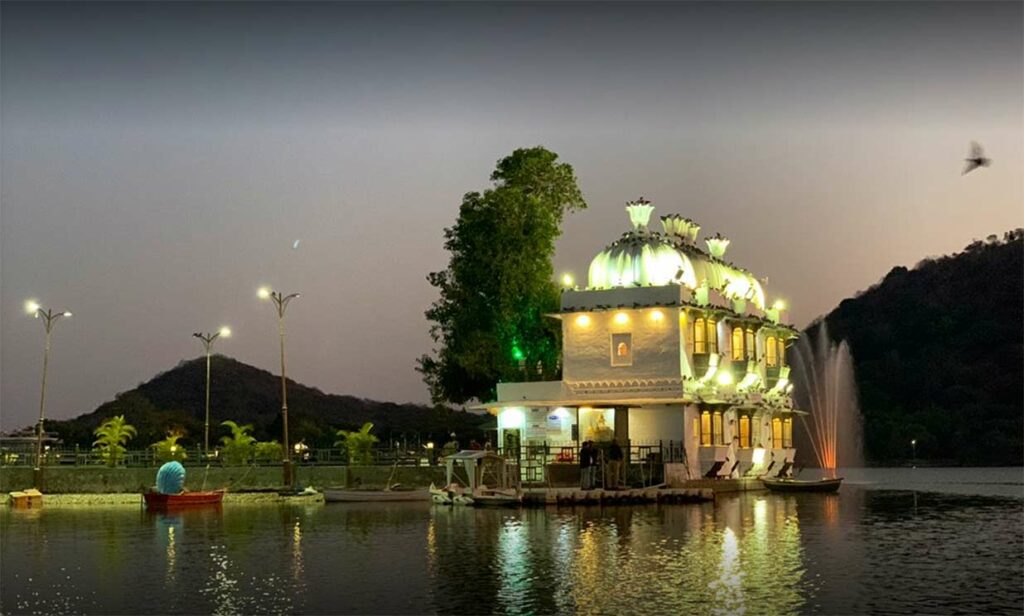

The Badal Mahal (completed in 1657) is also located on Lake Gaib Sagar and features a perfect marriage of Mughal and Rajput architectural style with a veranda, balconies and three domes crowned with half-opened lotuses. Originally built for recreational purposes, it was also used to accommodate state dignitaries. To be seen preferably in the evening when it is illuminated.

Around Dungarpur

Devsomnath temple (30 min)

My absolute favourite! This 12th century CE temple, dedicated to Shiva, is a small architectural marvel built on three floors without any mortar. Its particularity is its Garbhagriha (the main shrine) which is three meters below the ground.

During the descent into the sanctum sanctorum, we are like teleported into another world where the stones seem to make us hear the echo of past times.

Temple jaïn Rishabdev (1h)

Rishabdev or Rishabhadeo is located 1 hour from Dungarpur. It is a pleasant stopover on the Udaipur-Dungarpur road. High site of pilgrimage of Mewar, this small Jain treasure of the 14th century CE, with fifty-two pinnacles and 1100 finely carved pillars is dedicated to Rishabhdev (Adinath), the 1st Tirthankara (Saint Jain). Her 1 meter high image, sculpted in black marble, is represented in the padmasana position and, as a small particularity, she receives daily offerings of saffron (kesar in Hindi) hence her nickname “Kesariaji”.

Another specificity of this temple, it is not only venerated by the faithful of the Jain faith, but also by the Hindus who consider Rishabdev as one of the 24 avatars of the god Vishnu and by the indigenous Bhil community of the surroundings who venerate him as than “black god”.

Jaisamand lake

Jaisamand Lake or Dhebar Lake, 2 hours from Dungarpur, is reputed to be the second largest artificial lake in Asia. It was created in 1685, during the reign of Maharana Jai Singh, after building a dam on the Gomti River.

In total, the lake is made up of seven islands, one of which is still inhabited by the Bhil Meena tribe. There is also a nature reserve of the same name which serves as a habitat for various types of birds, panthers, leopards, deer and wild crocodiles. On its shores, Lake Jaisamand includes a temple to Shiva, as well as six cenotaphs carved in white marble.

N.B : part of the road is bumpy, the advantage is that we pass through several adivasi Bhil villages.

How to get there

By car: it remains the best solution if you want to stop on the way to visit the various places of interest. The trip is the full length on the highway, so the road is in very good condition.

Udaipur – Dungarpur | 2 hours | highway

Ahmedabad – Dungarpur | 4 hrs | Highway

By air: Maharana Pratap Airport in Udaipur, 124 km away, is the nearest airport. Foreign travelers can land at Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport in Ahmedabad, 146 km from Dungarpur.

By Train: Dungarpur Railway Station, 3 km from the main town, connects Dungarpur to all major and minor destinations in India. Kundagarh Railway Station at Kunda, 146 km away, can also be a good option to reach Dungarpur.

By Bus: Buses are readily available to Dungarpur from all major and minor towns in Rajasthan and North India. The city is barely 20 kilometers from the NH8, which connects Delhi to Mumbai.