Parasrampura, the oldest frescoes of Shekhawati

Among the countless small architectural gems of Shekhawati, the Chhatri of Parasrampura figures prominently. It houses the oldest frescoes of the region, illustrating in a simple, yet exquisite way, the princely life of Thakurs of the 18th century and some episodes from Hindu mythology.

Parasrampura is a village in Jhunjhunu district, located about thirty kilometers southeast of Nawalgarh, another culturally important town in the Shekhawati region.

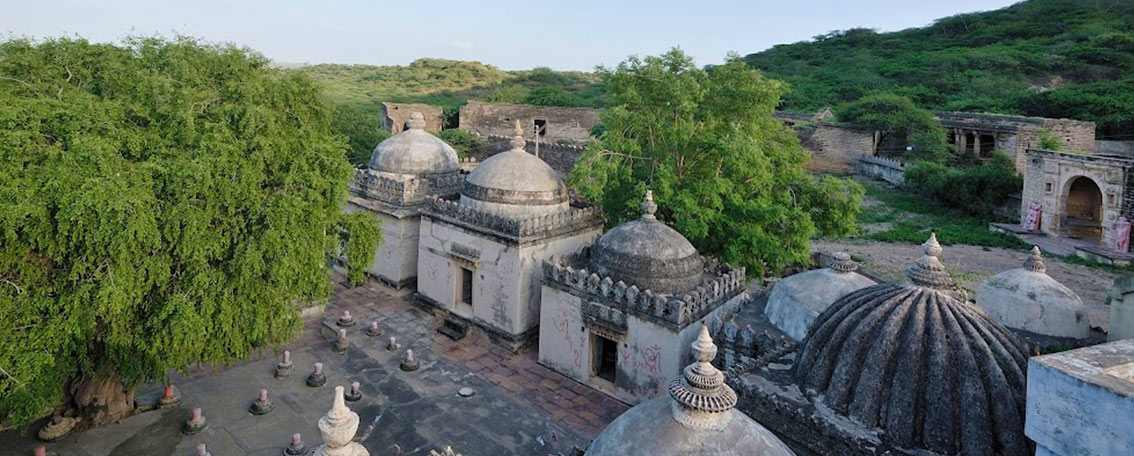

The small town does have a few interesting old havelis and temples, but the main interest lies elsewhere, under the dome of a “Chhatri” (cenotaph) erected in 1750 in memory of Thakur Shardul Singh (local lord) by his heirs.

From a distance, the Chhatri is not that much attractive, placed in a rather poorly maintained courtyard and surrounded by several small minor pavilions. If my guide hadn’t drawn my attention to this building, I could have easily missed this little treasure.

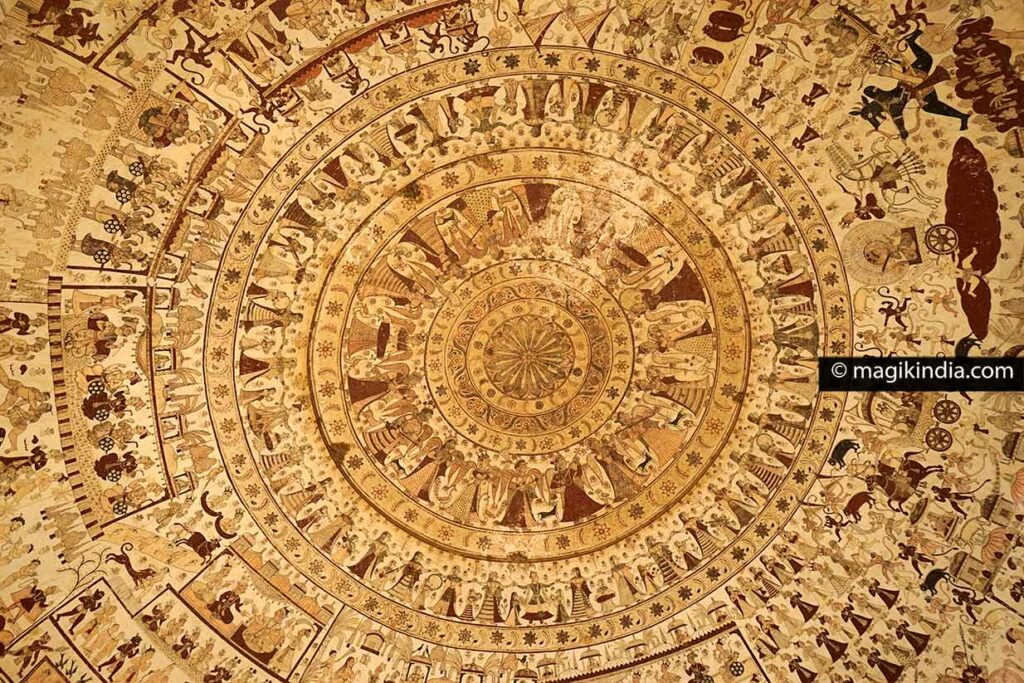

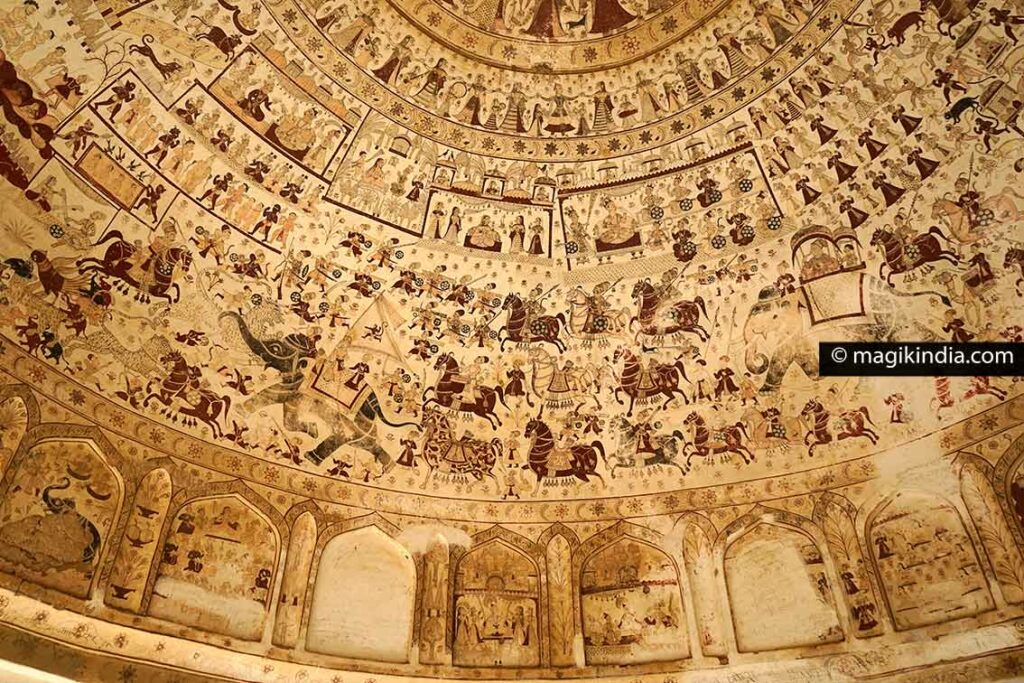

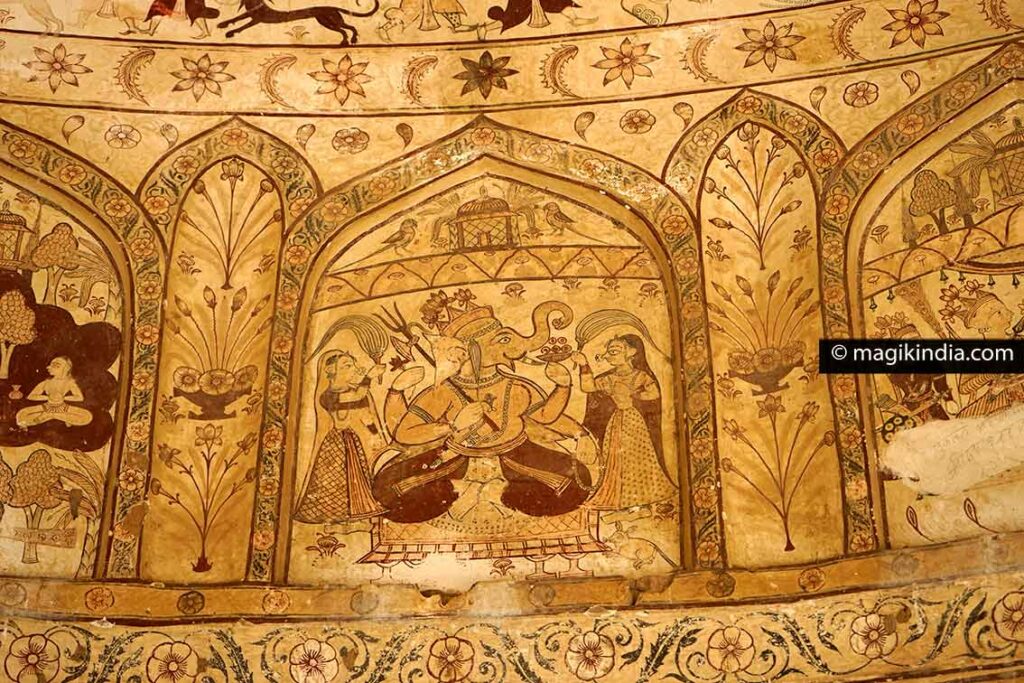

As we get closer to the cenotaph, it finally reveals all its beauty. Twelve octagonal pillars support a large dome inside which an abundance of miniature paintings are painted in ocher and black tones. And this is also its uniqueness. Here, no flamboyant colors or frills, simplicity par excellence.

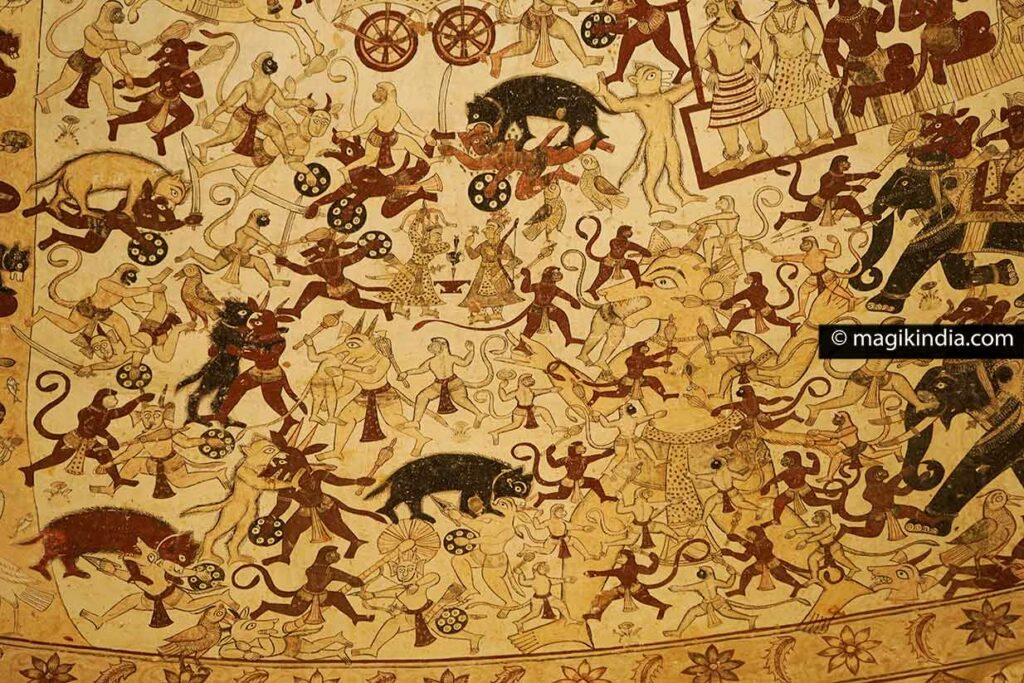

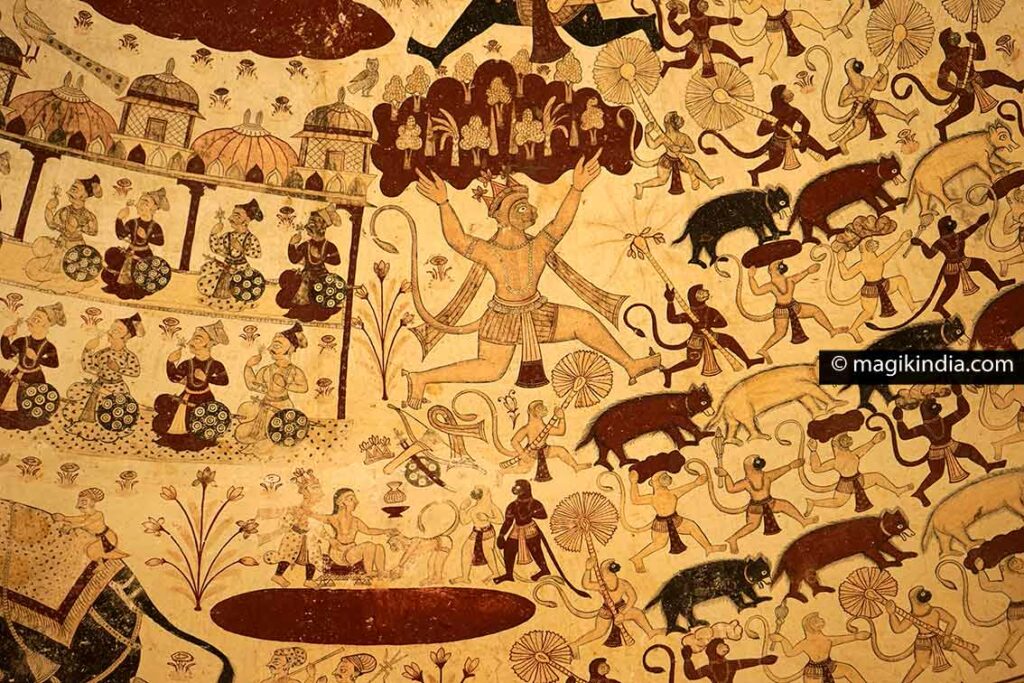

These frescoes depict events in the life of Thakur Shardul Singh, intertwined with episodes of Hindu mythology. Much of the paintings illustrate the penultimate battle of the Ramayana*, when Rama and his armies of monkeys and bears fought Ravana and his hordes of demons.

*The Ramayana is the shorter of two Sanskrit-language epics composed between the 3rd century BC. AD and the 3rd century AD. Attributed to the sage Valmiki, it consists of seven chapters and 48,000 verses. The Ramayana is, like the Mahabharata, one of the fundamental texts of Hinduism. It recounts, in brief, the birth and upbringing of Prince Rama, seventh avatar of the god Vishnu, his marriage to Sita, his exile, Sita’s abduction by the demon Ravana, his deliverance and Rama’s return to the throne.

The battle scenes in the fresco show some members of the army of Hanuman (the monkey god) engaging in deadly combat, while others carry stones to build the Rameshwaram land bridge to Lanka (Sri Lanka), necessary for the final siege of Ravana’s fortress and the rescue of Sita, Rama’s wife.

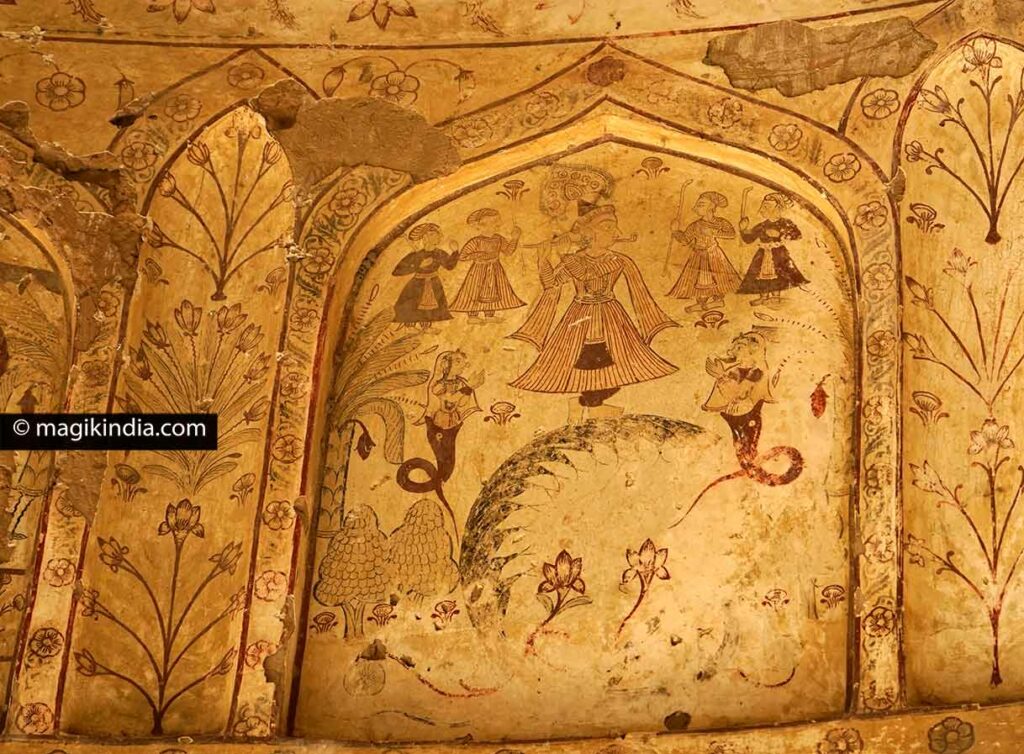

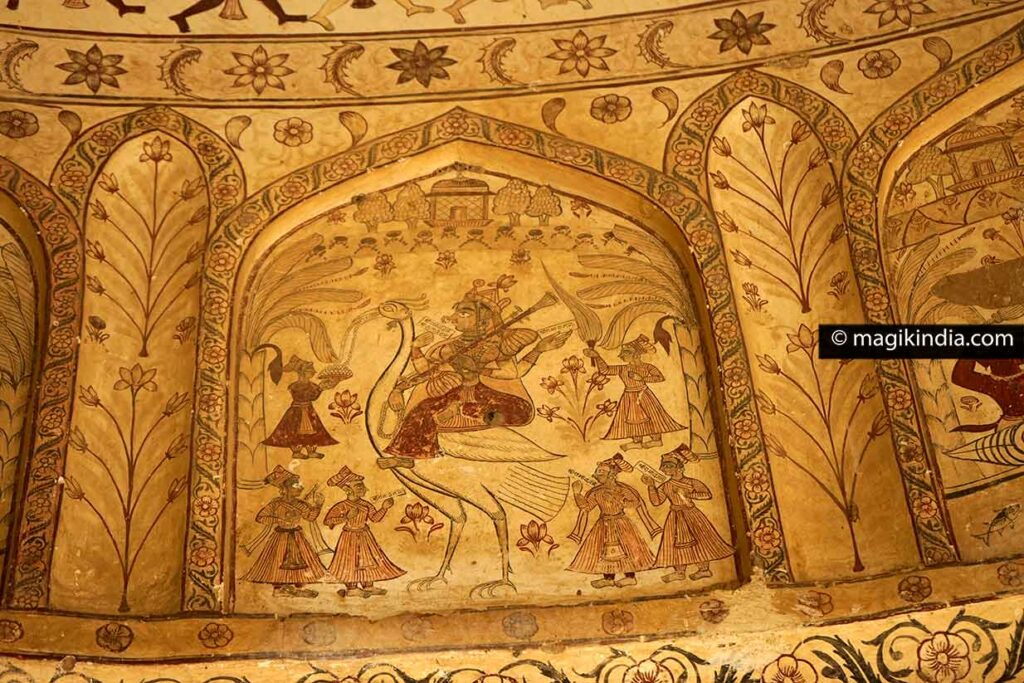

The lower panel of the dome, partly damaged, consists of deities painted in niches. In particular, we see a fine illustration of Saraswati, goddess of the arts and knowledge, mounted side-saddle on a sign, her “vahana” or divine vehicle. She holds her traditional attributes in her four hands: the veena (a kind of lute), a mala (rosary), and holy scriptures.

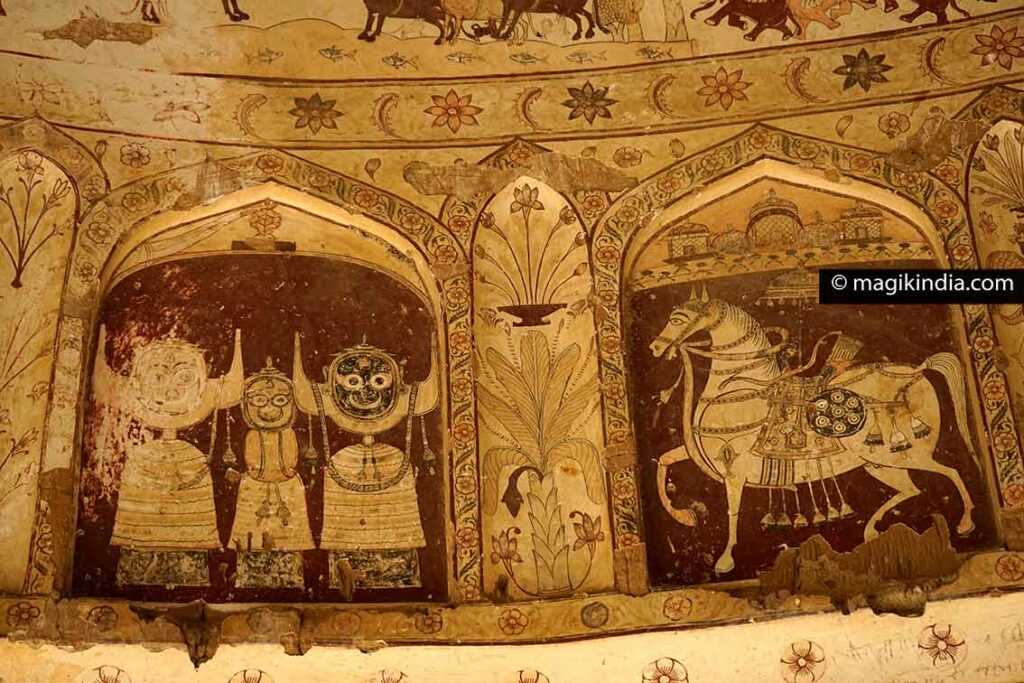

There are also images of the elephant-headed god Ganesha and the three singular deities of the famous temple of Puri: Jagannatha (the god Vishnu), Balabhadra (his brother) and Subhadra (his sister).

Another drawing illustrates a scene from the Kaliya Daman where Lord Krishna dances on the head of the serpent king Kaliya.

In Hindu mythology, the Kaliya is a serpent-demon that boiled the waters of the Yamuna River, creating a poisonous breeze that killed everything in its path. Krishna danced on his head to stop his misdeeds.