Banswara, the land of Bhil people

Rajasthan is often associated with the arid lands of the Thar Desert. But the “land of the kings” is crossed by the Aravalli mountain range which, during the monsoon, is wonderfully green. This the case of Banswara, located in the extreme south of Rajasthan that welcomes each year abundant rains, thus its nickname: the “Cherrapunji of Rajasthan”. In addition to its natural beauty, the city has a distinct entity linked to the Bhil community, the majority ethnic group of the region, which fought against the feudal system of the Maharawals and the British Raj.

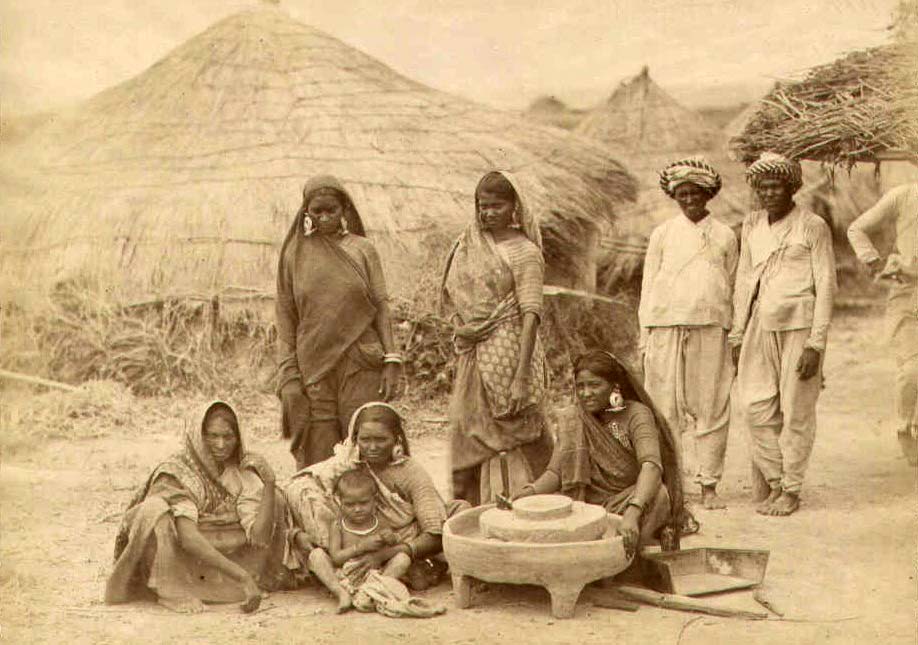

“Banswara, the land of the Bhil people”. This title was not chosen at random. This is my tribute to the Bhil people and, more generally, to the indigenous peoples, called “Adivasi” (first peoples) in India.

Aborigines, whether in India or elsewhere, have been and still are victims of repeated discrimination. Some bow down, others on the contrary struggle to assert their rights. This is the case of the Bhil people of Rajasthan.

At the beginning of the 20th century, under the leadership of Govind Guru, a social reformer from Gujarat, they rose up, not only against the oppression of the British Raj, but also against the local princes: they refused to submit to forced labor and to pay exorbitant property taxes on their own land.

On November 17, 1913, when they had gathered on the hill of Mangarh, the center of their faith, the British army, in retaliation, fired on the crowd and killed 1,500 of them. This massacre, echoing that of Amritsar, is also known as the “Jallianwala Bagh” of Rajasthan. However, unlike the Punjab massacre, that massacre was never acknowledged by the British, nor does it appear in Indian history books. Are tribal peoples considered as second-class citizens?

In memory of this massacre of 1913, a monument was built on the hill of Mangarh, which has become in a way a symbol of the tribal identity.

After this little historical parenthesis, let’s discover the Banswara region.

On the road Udaipur – Banswara

Before arriving at Banswara, several stops are worth a look.

Paraheda Temple

The photos of this 12th century temple shown on the web were promising but, in the meantime, an “architectural crime” has been committed there! On the upper part of the temple and inside the sanctum sanctorum, the old weathered stones have been colored in pastel shades, what a pity!

As The building has not been classified yet as a historical monument by the “Archaeological Survey of India”, it seems that the locals have taken too many liberties with the renovation of the temple.

Fortunately, the friendly atmosphere inside the sanctuary with its typical sadhus and villagers saves the day.

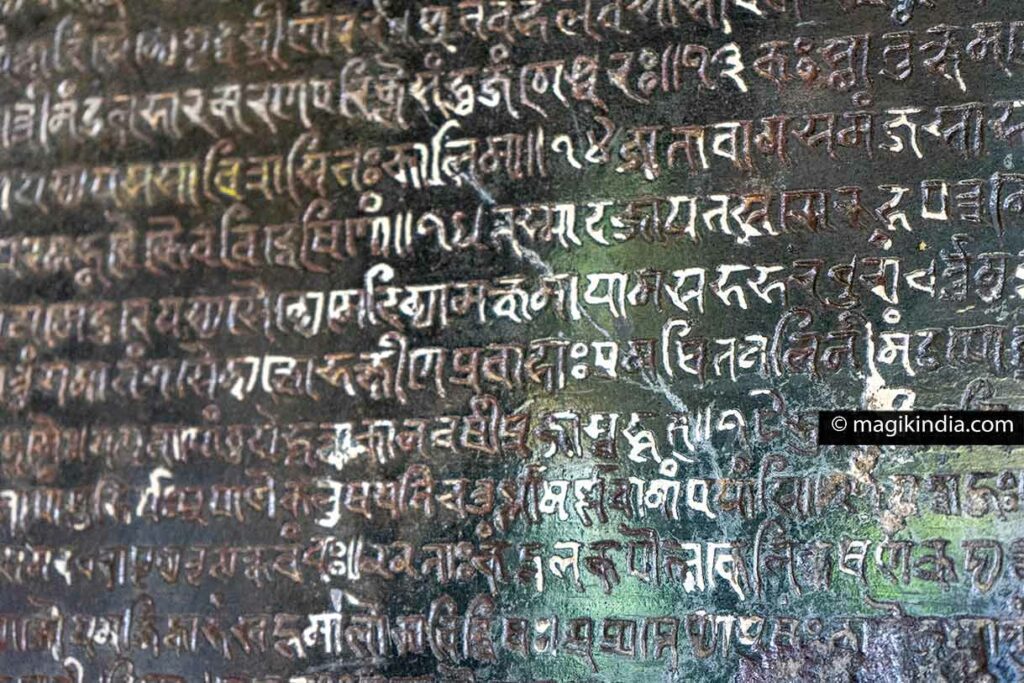

At the four corners of the temple, beautiful statues are carved in grey stone, barely saved from the “painting madnes”. Near the entrance, a plaque bearing inscriptions in Sanskrit reminds us of the antiquity of the temple.

Ram Kund (Phati Khan)

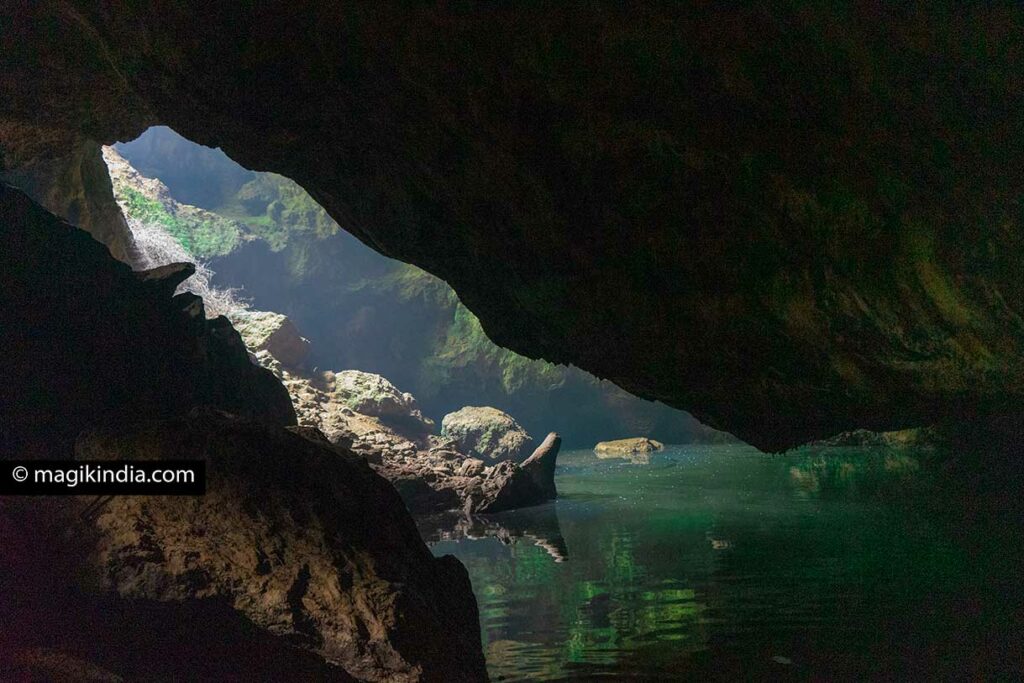

We continue on the same road and come across a mysterious place: a 400 m deep cave where a spring with jade-colored water flows. Popular legend has it that Lord Rama, his spouse Sita and his brother Lakshmana stopped here to rest during their 14-year exile.

The cave, in addition to its body of water, has several small temples; the main one is dedicated to Shiva where the local villagers come to offer their prayers.

Tripura Sundari Ma Temple

On the same road, near Talwara, there is the temple of Tripura Sundari Ma, one of the most revered shrines in the region.

It is dedicated to the Shakti, the Divine Mother, represented by a black schist statue of Durga with eighteen armed arms and seated on her tiger-vehicle (Vahana). If the structure of the temple is recent, the foundations, predate the Kushan dynasty which reigned in the 1st century of our era.

We continue our journey accompanied by splendid landscapes, which sometimes look like a typical postcard of Kerala. We enter Talwara.

Talwara

Talwara is a large village renowned for its marble sculptors; several of them have settled on the main road towards Banswara. There are also some interesting temples, that of Amaliya Ganesh in particular.

Banswara

We arrive at Banswara. The city itself is of little interest. There is a fort at the very top of the city, which again looks very impressive on the photos, but it is in reality abandoned. I couldn’t get in. The inhabitants themselves admit they have never visited it.

The main asset of Banswara is its natural environment consisting of lakes, waterfalls and dense forests. For this reason, the best season to go there is during the monsoon, from July to September when Mother Nature wraps herself in a long soft green coat.

Kagdi Pick-up

Located on the eastern part of the city, the Kagdi Pick-up is made up of a large lake where many migratory birds come to rest. It is a family place and, apart from its entrance arch, the place is not a must stop.

Madareshwar temple

To the northeast of the city, on the hillside, a temple dedicated to Shiva has been dug into the mountain. An imposing Shiva-lingam is placed in the middle of the cave.

During the Kanwar Yatra, an annual pilgrimage dedicated to Shiva (in July or August), devotees bring back holy water from the Ganges of the city of Haridwar or Gangotri, which is offered to the lingam of Madareshwar.

Chacha Kota (17km)

The pearl of Banswara! “Chacha Kota” is an enchanting place located about fifteen kilometers from the city. This region dotted with islets, was formed around the backwater of the Mahi River, which extends over a distance of forty kilometers. Because of this peculiarity, Banswara is also nicknamed “the city of a hundred islands”.

To reach Chacha Kota, we must take a winding and zigzagging road through several hills; the fifteen kilometers seems to be getting longer.

But it worth it! The coast cut out by what looks like a sea from afar and the intense green of the hills is amazing and evokes the wild landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. The panorama is so captivating that I am seized with a photographic frenzy that undermines the patience of the people accompanying me.

As I stop for the umpteenth time to admire this dream landscape, punctuated by isolated earthen houses, a boy and his two young sisters from the Bhil community come timidly towards me, and here is the photo above!

Continuing on the same road, one comes across the Mahi Bajaj Sagar dam, which is the largest water reservoir in the Udaipur division. I didn’t go there, priority to the wonders of the Singpura region.

Singpura

Singapura is the other treasure of the Banswara region, located south of the city and made up of forests and green valleys.

The main purpose of the visit is the Singpura Waterfall, at the top of the area, quite an adventure!

The GPS doesn’t work anymore and we have to ask our way several times to the local villagers who answer us in Hindi mixed with the local dialect. Actually, it’s a great opportunity to meet the inhabitants and share precious moments with them.

We arrive somehow at the right place. The car stops there. We must continue on foot. The starting point is a small lake surrounded by thick forest. We ask our way to a boy whose house is at the edge of the body of water: we still have 2 kilometers of walking through the jungle before discovering the waterfall.

The monsoon having been poor this year, the waterfall has only a meager trickle of water. I post here the photo of a surfer showing the waterfall in all its splendour.

The Banswara region includes other waterfalls, also worth seeing during the monsoon: Jua, Kagdi, Kadeliya, Bhuadara, Jhulla and Kushalgarh.

Arthuna Temple (55 km)

About fifty kilometers from Banswara, the ancient temples of Arthuna are a destination not to be missed. Built in the 11th and 12th centuries CE by the rulers of the Parmar dynasty, who made Arthuna their capital, the complex brings together shrines of the Hindu and Jain faiths.

The major temple is that of Mandleshwar Shiva (1080 CE), built by Raja Chamundaraj in memory of his father, Raja Mandalik. It is still in operation and the inhabitants visit it daily to offer their prayers.