Gavari, the mystical folk-theatre of the Bhils

The indigenous people of India (adivasi) are guardians of many ancient traditions expressed during festivals that can transport us to other worlds. Simultaneously, these traditional activities can evoke something somehow familiar, perhaps common roots echoing within us. Gavari is one of these festivals. This mystical folk-theatre of the Bhil people of Rajasthan is expressed through several acts composed of incantations, sacred songs, social satire and ecstatic dances.

The origin of Gavari (गवरी) still remains mysterious, some believe that it may have been created in the 16th century in reaction to the oppression of the Rajput rulers gradually depriving the Bhil people from their ancestral lands. Others believe that this festival is as old as the Bhil people themselves, i.e. millennia.

The festival starts every year in August, a few days after Rakhi, the brother and sister festival and lasts for 40 days.

Although many characters evolve throughout the play Gavari is, in the first instance, dedicated to the Hindu goddess Gauri or the “Shakti”, the primordial force of creation.

This adivasi theatre, originally spiritual and mythological, has evolved and been adapted in the context of historical moments by the inclusion of social and political events such as the British colonisation.

Gavari is restricted to the Mewar-Vagar region and mainly to the districts of Udaipur, Rajsamand, Chittor and Dungarpur. It brings together up to thirty Bhil communities, dispatched in groups of 20 to 50 members, who go on tour to different villages in the region. More than 500 performances take place annually.

Highlights of Gavari

In order for Gavari to take place each village must receive permission from the goddess Gauri who intervenes approximately every five years. When, after invoking the deity, one of the villagers enters a trance, as if possessed by the Shakti, this is a sign that the village has been chosen to host the festival.

The newly constituted troupe, composed mainly of Bhil farmers, will then set off to play in about thirty villages. More specifically, in those villages where the sisters or married daughters of the members of the troupe live. In India women live with their in-laws after their marriage, this festival thus helps to maintain and consolidate family ties.

Gavari is also a time of austerity for the temporary actors. They must abstain from sexual intercourse, alcohol and non-vegetarian food and even from green vegetables. Some also choose not to wear shoes and to sleep on the floor. These are forms of purification found in several other Hindu festivals such as Navaratri or Mahashivaratri.

The village square acts as a circular open stage. The audience all gather round.

Before the play begins a Bhopa (a kind of shaman) invokes Gauri with prayers and pujas (rituals) with an idol representing the deity. A Dhuni, sacred fire, is lit and a Trishul (trident), symbol of Shakti and Shiva, is placed in the center of the stage, after which various offerings are made.

The piece consists of fifteen acts and can last up to 5 hours a day, with a series of incantations, mimes, parodies, devotional songs and ecstatic dances. The maddal (drum), the thali (gong) and cymbals are the only instruments that accompany the songs.

Apart from the start and end of the play, the content is not fixed (there is no script), but it constantly evolves and relies on the improvisational skills of each actor.

On the last days of the tour the play lasts late into the night. The forty days ends with a “visarjan” ceremony where the statue of Gauri is immersed in a pond.

[ Watch! One of Gavari’s acts invoking Ganesha, the god of auspiciousness]

The characters of the play

This folk-opera is made up of a multitude of characters.There are humans (members of different tribes, corrupted politicians, British officers, Rajputs) deities, demons and animals.

Among these characters three hold the main roles – the two “Mata Rai” and the “Budiya”.

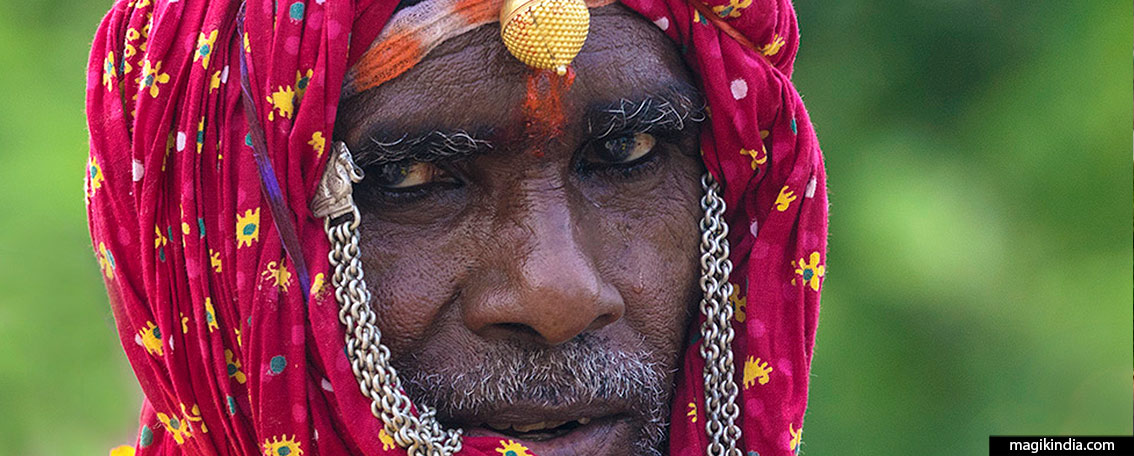

The two Mata Rai represent the goddesses Parvati (wife of Shiva) and Mohini (the only female avatar of the god Vishnu), generally sit in the center of the circle formed by the troupe. They are embodied by men wearing a tight turban encompassing a large part of the face, a bit like a Touareg tagelmust.

On either side of their faces two long silver chain jewels are hung, a typical tribal feature, and a maang-tikka is fixed on their foreheads, probably a Rajput influence. The “Rai” is certainly the most enigmatic character in the play.

The Budiya embodies Bhashmasur, a half-god, half-demon, and he is the only Gavari character to wear a mask. The mask is usually oval or round (but there are also rectangular ones) with hairs made of horse tail hair. Each Budiya mask is unique, considered highly sacred and is transmitted from generation to generation within the village.

Legend has it that the demon Bhashmasur was a devout devotee of Lord Shiva. The latter, as a reward for his devotion, granted Bhashmasur the power to kill, by fire, any person on whose head he laid his hand. But, Bhasmasur being a demon, abused this power and killed many innocent people. To stop him in his murderous madness, the god Vishnu, the protector of the universe, transformed himself into a Mohini dancer and went to see the demon. Fascinated by the beauty of the goddess, he began to imitate her dance gestures until she put her hand on her head. He died on the spot. The demon’s soul then implored Shiva to forgive him and in return the lord of Mount Kailash granted him the right to be worshiped at the Gavari festival.

[ Gavari dances with the Budiya ]

The Budiya, armed with the “Chhari”, a sacred wooden stick, has the task to go around the stage in the opposite direction of the circle of performers during the opening invocations to prevent outside intrusions. He then periodically stands around the edge of the circle to accept offerings on behalf of the troop and confer blessings.

When one attends Gavari for the first time, one is surprised to see men wearing women’s jewelry, giving the impression of hijras, transgender people of India.

But there is no link with the hijras. In reality, women are excluded from Gavari performances -mainly because of their menstruation (often perceived as impure in India) which necessarily occurs during the 40 days of the tour, the men then take on the female roles of the piece.

The other two recurring characters in the play are the Meenas and the Banjaras. The Meena community are also part of the aboriginal people of India known to be fierce warriors in times past.

The Banjaras, on the other hand, are originally a nomadic people. Famous traders and transporters of goods in the interior regions of India. During their wanderings, more precisely when they had to cross the thick jungle of the Aravallis mountains, the Meena ensured their protection. In exchange, the Banjaras paid them a tax.

The Banjaras sometimes were reluctant to pay so scuffles ensued which are transcribed in the Gavari.

Gavari, an endangered art?

As it is the case with many traditional arts in India which tend to coalesce into an increasingly homogenized mass, Gavari theatre could soon be classed as an “endangered” art.

There are several reasons for this.

Education which has spread widely in India (and this is a great step forward), paradoxically penalizes the transmission of this performing art. Gavari is not learned in books but on the ground. However, few schools allow Bhil children to take time off to take part in performances.

Moreover, this art is not remunerated nor really highlighted. Few young people are interested in taking up the torch, more attracted by the siren song of the megalopolises.

Fortunately, in recent years, some groups have decided to take matters into their own hands. First of all, the Bhils themselves, who have united, as well as local NGOs.

In 2016 the government program “Rediscovering Gavari” was created, allowing 12 troupes to come and play Gavari in different emblematic places of Udaipur. This has allowed national and international tourists to discover this extraordinary theater.

To better protect this Adivasi heritage these same groups are campaigning for Gavari to be classified as “UNESCO intangible cultural heritage” as is, for example, the Baul music of West Bengal.

KNOW MORE ABOUT GAVARI (“rediscovering GAVARI”)