The Toran Marana of Rajasthan

While strolling through the cities of Rajasthan, perhaps you have already noticed this pentagonal wooden decoration placed above the front door of a house. This element called “Toran” or “Torana” is an integral part of Hindu wedding ceremonies in Rajasthan and, under its simple appearance, it has a strong symbolism.

The legend of Toran

The Toran is associated with a popular legend.

It is said that in ancient times there was a demon named Toran, who took the form of a parrot and waited patiently at the entrance to the house of the future bride. When the groom attempted to enter his bride’s house to finalize the wedding ceremony, the demon bird would jump on him and take possession of his body and then marry the bride.

History repeated itself for a long time until a wise prince unmasked the bird and struck it down.

It is said that since those times, the bride’s family hangs a Toran decorated with parrots above their front door before the wedding ceremony.

During the last stage of the wedding (see my article on the Rajasthan wedding), the future groom, preceded by a procession, leaves for the wedding venue on horseback (baraat) or on the back of an elephant for the wealthiest families. Before entering this place*, the groom touches the Toran seven times using a branch of neem and/or a sword.

This action is supposed to recreate the death (marana) of the parrot-demon and allows the marriage to start under good auspices.

*The place of the wedding is traditionally the house of the bride. These days, weddings are most often held outdoors to accommodate a larger number of people. The Toran is then placed at the entrance to the reception hall, then will be hung on the main door of the groom’s in-laws.

This legend has its roots in a somewhat less resplendent reality that prevailed in medieval India. It happened very frequently that the fiancée was kidnapped by another suitor and that she was forced to marry, forever sullying the reputation of the young woman as well as that of her family. The Toran was therefore formerly used to ward off bad luck by symbolically killing the “parrot-impostor-kidnapper”. Although fortunately times have changed, the tradition continues today.

The symbolism of the Parrot

Sensuality and fidelity

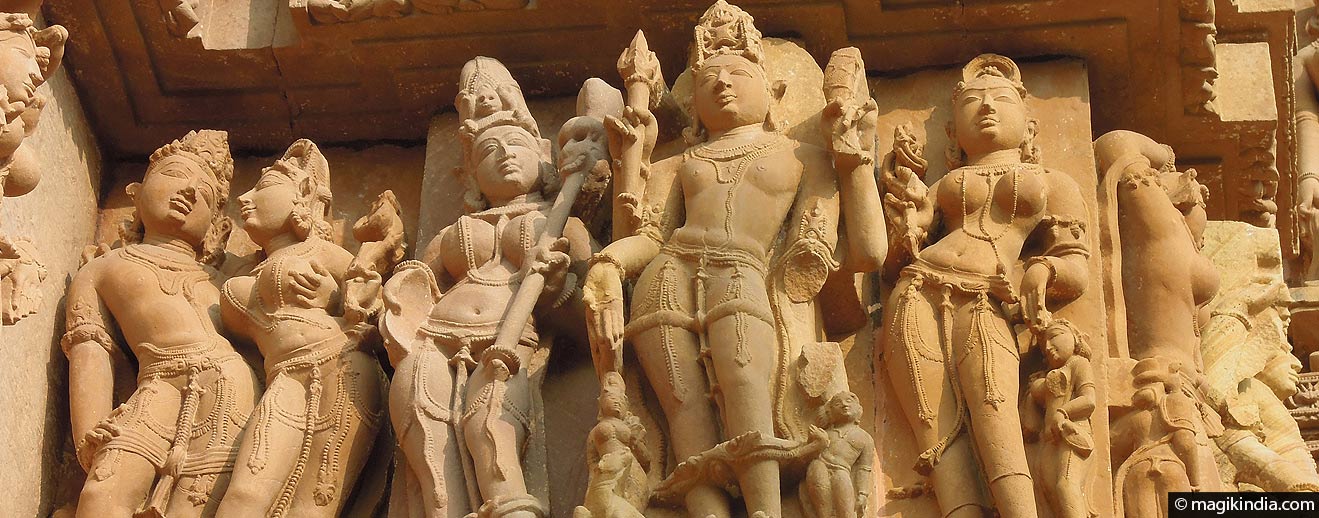

It is not by chance that the parrot, or more precisely the parakeet, (suka in Hindi) is used in the Toran. It is a recurring element in the imagery of Hinduism.

According to Hindu mythology, the parrot is the pet of Kama, the god of love, of seduction and of carnal pleasure. Also, in some cases, the parrot has a very strong sexual connotation.

To illustrate my point, I refer here to the cycle of stories “Suka-Saptati” or the 70 fables of the parrot, a famous example of Indian classical literature of the 12th century with a ribald and uninhibited content. Here is an excerpt:

“The best of all beds for lovers is higher at the sides and sunken in the center; thus, moreover, it will better withstand the jolts of the couple’s passion.

The average bed is flat, so the night passes with little contact between the two bodies.

The worst of the beds is domed in the center and its two sides slope downward; even the experts of this art cannot make love there continuously” (this last phase makes me particularly smile!).

In this collection, the stories are told by a pet parrot to his young mistress, Prabhavati, in an attempt to distract her and prevent her from meeting her lover during her husband’s absence on a trip abroad. For seventy nights, the bird keeps the heroine at home with juicy tales of illicit affairs and the complications that follow.

The parrot, divine messenger and transmitter of knowledge

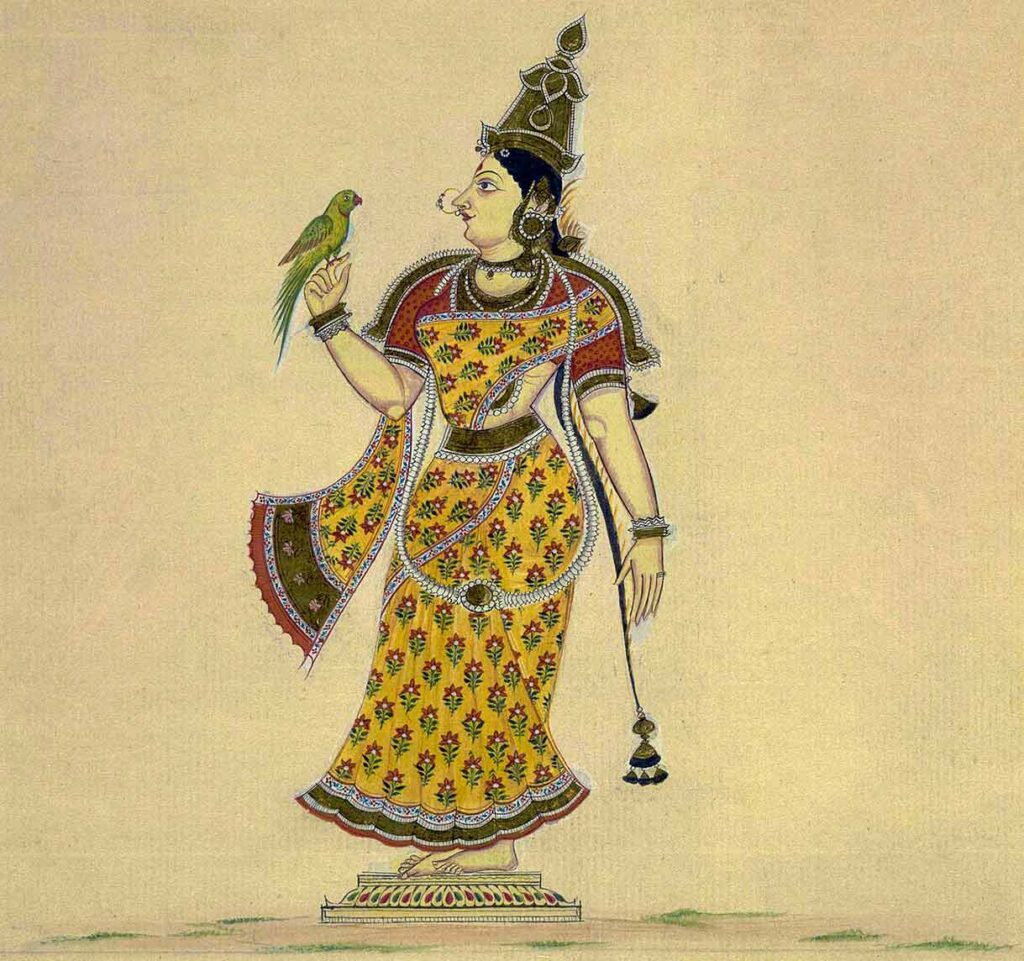

In South India, the parrot is one of the attributes of the goddesses Meenakshi and Kamakshi (two forms of Parvati), as well as Andal (avatar of Lakshmi), the only woman among the twelve Alvar saints of Tamil Nadu.

The parrot, in this case, is not only a messenger of divine love (Andal’s parrot would send sweet words to Vishnu) but also a transmitter of knowledge: Meenakshi’s parakeet, for instance, transmitted to him the knowledge of the Chatushashti Kalaa, the 64 essential arts of the Vedas.

The popular belief is that where a parrot is, it is Sukha Brahmam who repeats the Bhagavata Purana, one of the eighteen major Puranas or sacred texts of ancient India. It is said that Sukha Brahmam took the form of a parrot after his physical death to tirelessly repeat the sacred scriptures.

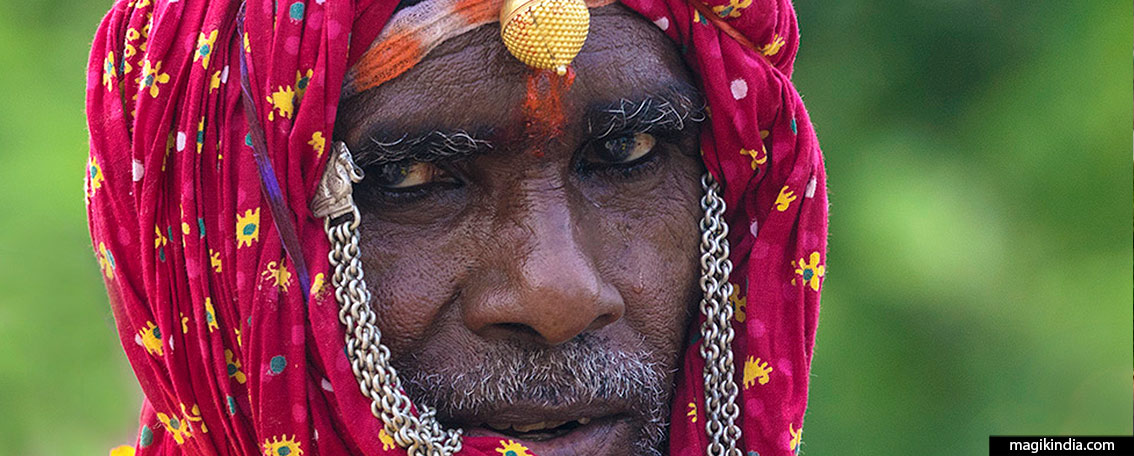

Parrots are, moreover, decked out with divinatory powers. Those who have already visited India may have witnessed the drawing of cards by parrots. The bird challenged by its master comes out of its cage and chooses a card which will then be interpreted.

The Ramayana epic also tells that when Sita and Rama went into exile, they disguised themselves so as not to be recognized. When they passed by the holy Purandhara Dhasar, he paid them no attention as a parrot perched on a branch shouted “Ram Ram, Sitha Ram!”

As we have just seen, the parrot is a powerful symbol in India, as much attached to earthly things as to spiritual things.

The different forms of the Torana-marana

For pandits (Hindu scholars), the original form of the wedding Toran is that composed of a wooden structure on which are represented parrots and only parrots, for the reasons we mentioned at the beginning of the article.

Over time, the elephant-headed god, Ganesha or/and the swastika cross appeared on the Toran. According to purists, this is nonsense because, instead of symbolically slaying the parrot-demon, Ganesha is killed, who is supposed to bring luck and remove obstacles.

For others, Ganesha has its justification, because the parrots around the god symbolize the eleven “Ganas”. In Hinduism, the Gaṇas are the soldiers of the god Shiva and their leader is none other than the god Ganesha. These birds are then considered the protectors of the house.

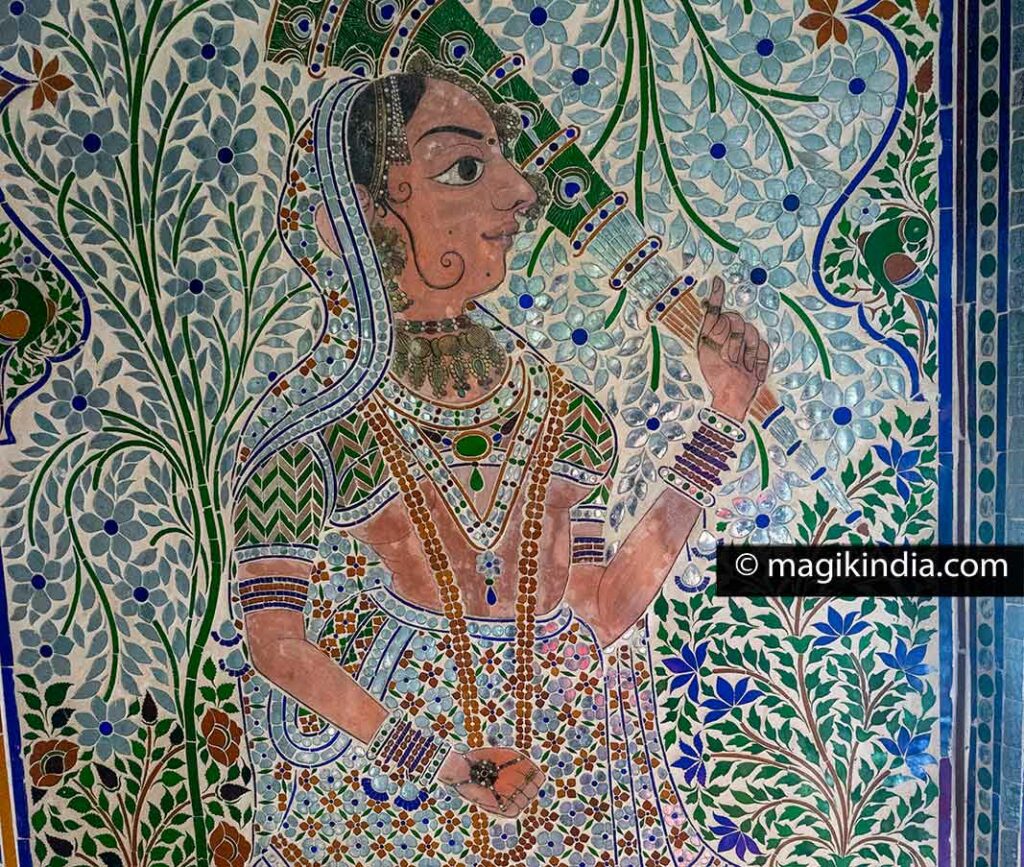

The name Toran is also given to the decorations in fabrics or mango leaves adorning the main entrance of the house; they are usually placed on festive occasions like Diwali, the festival of lights, to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity.

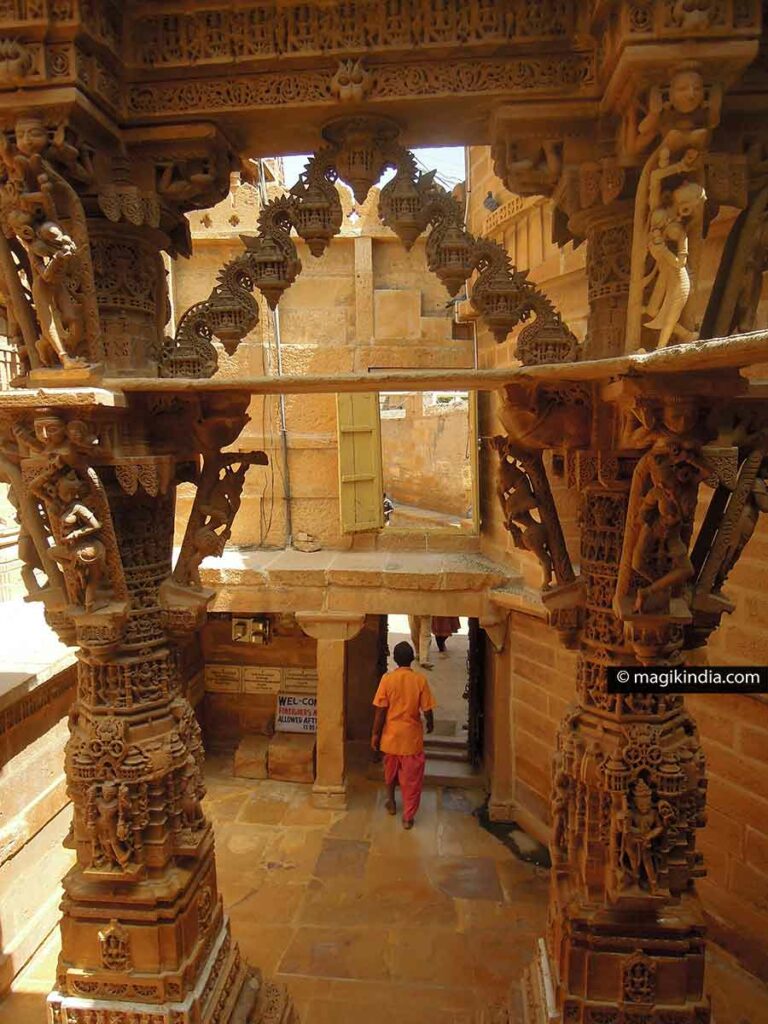

In Hindu, Buddhist and Jain architecture, the Toran also designates an ornamental arch built for ceremonial or commemorative purposes, for example to mark the victory of a ruler.