The Havelis of Rajasthan, bioclimatic mansions

The climate has always been one of the determining factors for the design of living spaces. Thanks to very specific construction technologies, the haveli, translated as “mansion” in English, is an ingenious architectural response to the extreme climatic conditions of the regions of Rajasthan, providing passive means of heating and cooling, while respecting the environment. Thus, this type of residence, which sometimes takes on a palatial appearance, was, long before the term was used, a bioclimatic building and a model of sustainability that still inspires nowadays architects.

Haveli derives from the Persian word “hawli” meaning “partition” or “enclosed space”. This type of building is found throughout India, but particularly in northwestern India (Rajasthan, Punjab and Gujarat), where large climatic variations pose challenges in terms of living comfort.

If we take the city of Churu, for example, in the northeast of Rajasthan, we observe temperatures that oscillate between 3 degrees in winter and 50 degrees in summer; this is a considerable difference.

It is for this reason that Rajasthan is surely the state that offers the most perfect model of what the concept of haveli ; the best exemples are the golden city of Jaisalmer and the region of Shekhawati and, to a lesser measure, Bikaner and Udaipur.

If the architecture of the haveli was a direct response to the regional climate, it was also a reflection of the opulence of its designers, wealthy merchants, who made their fortune thanks to the Silk Road.

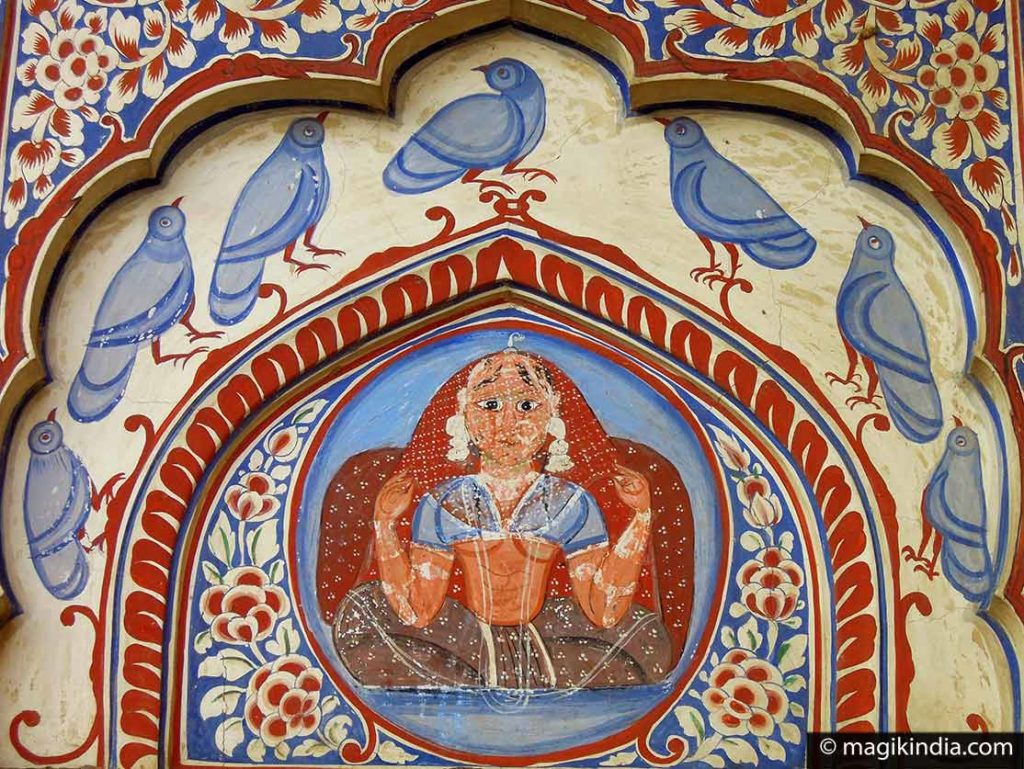

In the Shekhawati region, northeast of Rajasthan, it was the Banias Marwaris who, in the 17th century, built sumptuous residences adorned with a profusion of colorful frescoes. The area has, due to this, been dubbed the open-air art gallery of India.

In Jaisalmer, West of Rajasthan, the most majestic residence, the Kothari Patwa haveli, was built by the Jain Patwa family who were immensely successful in finance as well as in the brocade and opium trade.

As for the red havelis of Bikaner, a city close to Shekhawati, they were erected in the 17th century by the wealthy family of Rampurias merchants in an eclectic style that makes them so charming.

Architectural influences of the haveli of Rajasthan

The Rajasthani haveli is an architectural structure that developed from the end of the 16th century under the influence of the Mughal style which is a fusion of several architectures: indigenous, Persian Islamic and Central Asian. This type of architecture typical of Rajasthan is generally referred to as “Mru-Gurjara” or, more popularly, “Rajput”.

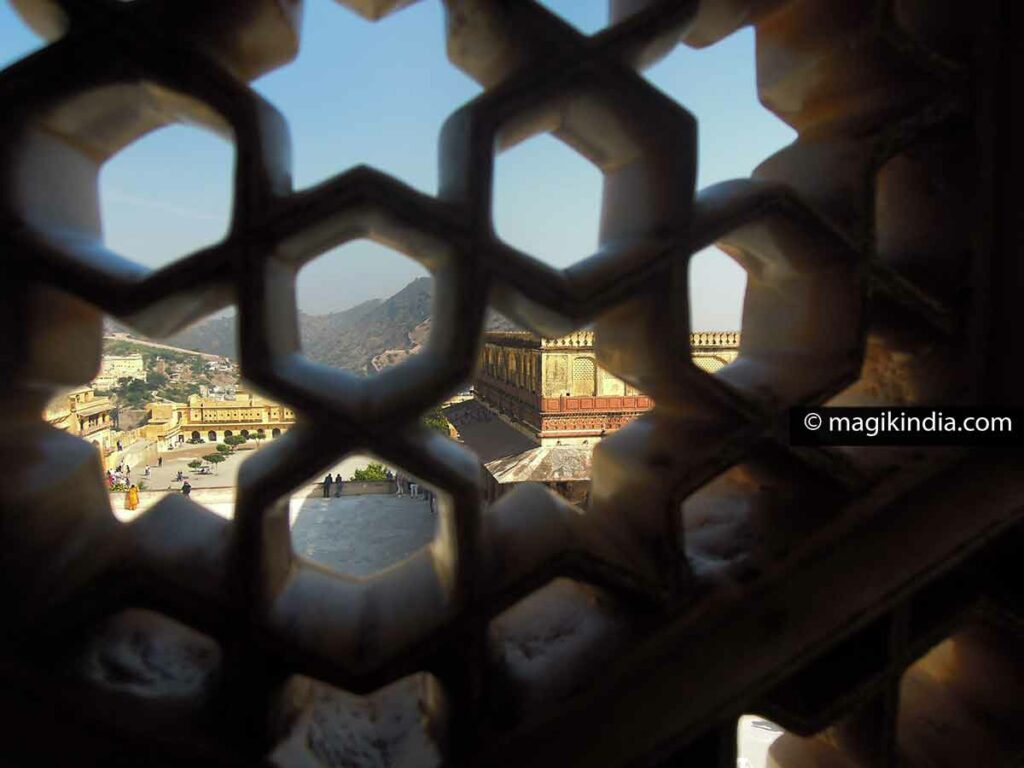

Among the most distinctive characteristics of the Rajasthani style is the Jharokha, a corbelled balcony, closed with jalis (openwork walls) and crowned with a semi-dome with acute angles.

Its purpose was not only aesthetic but also utilitarian: it allowed good ventilation of the house, possibly positioning guards or soldiers and was also used for the official appearances of the masters of the mansion.

Another inseparable element of the Rajput style is the chhatri (which means umbrella in Hindi). It is a pavilion with a kiosk supported by several pillars with polylobed arches surmounted by a hemispherical dome with a projecting awning.

Chhatris can be purely ornamental or serve as cenotaphs at the cremation ground of Rajput lords.

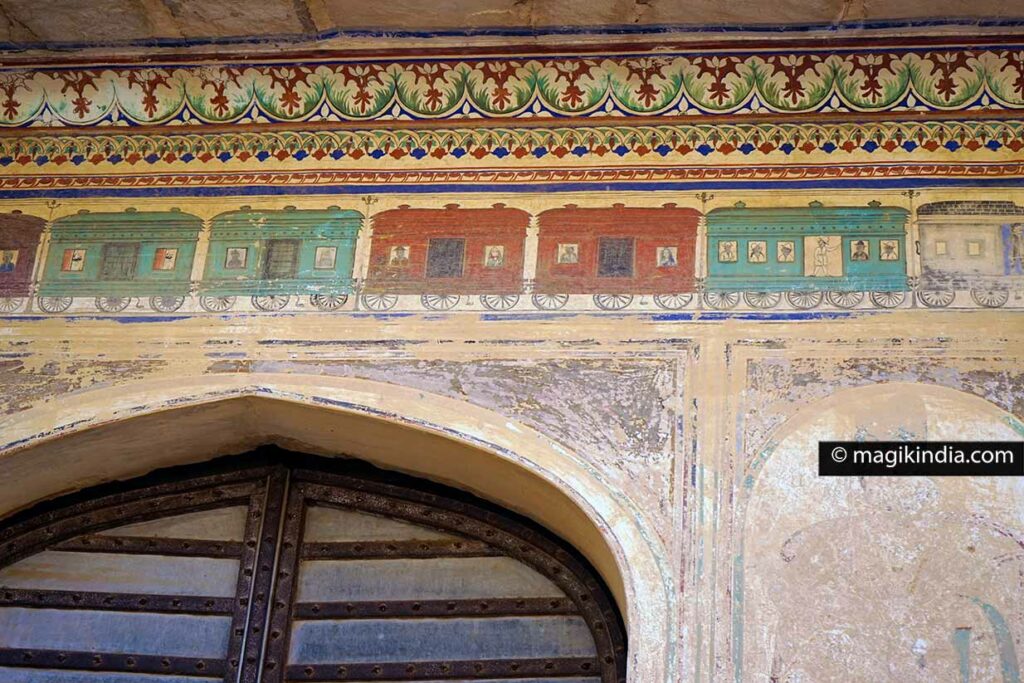

During the British Raj, the architecture of the havelis will be strongly influenced by the Victorian and European style in general, this is especially the case for the Shekhawati region.

The interior pillars and the floors of the havelis then are of Italy style, the stained glass windows and chandeliers are brought back from Belgium and the frescoes on the walls which until then displayed the life of the god Krishna, are now adorned with contemporary motifs: steam trains, bicycles, telephones, cruise and ships.

Western characters also find their way into these murals, Frida Kahlo, the Mexican painter, being the most anecdotal example.

Havelis have some typical features that include courtyards, verandas, balconies, thick walls, and materials like brick, natural stone, and lime that come into play in thermal regulation.

The chowk, one of the major thermal regulators of the haveli

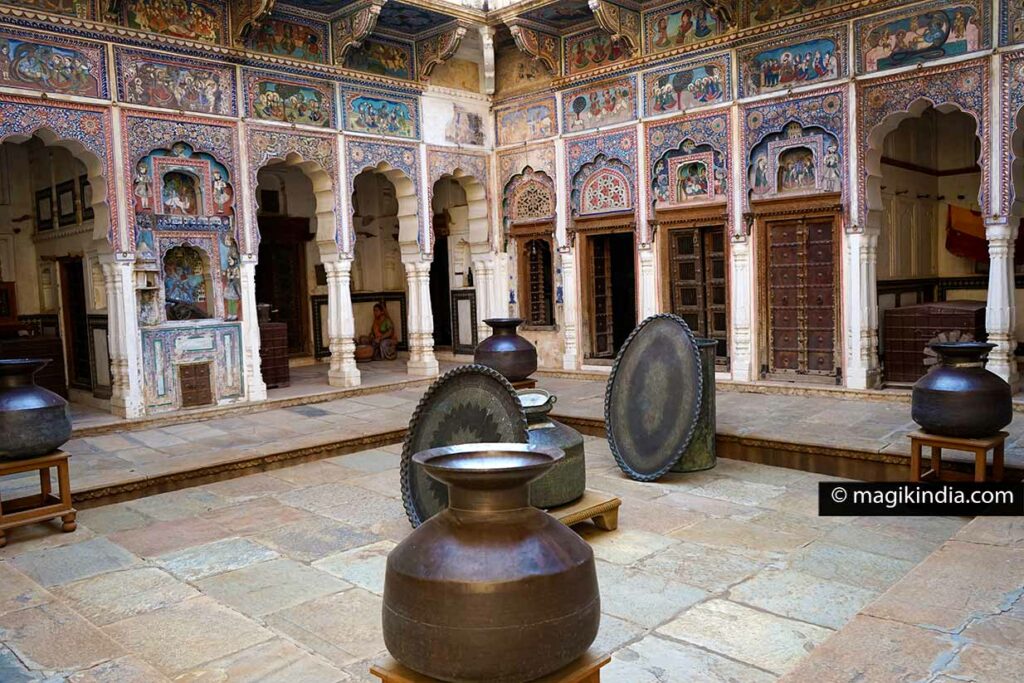

Havelis are built around one or more interior courtyards called “chowk”. True heart of the building, the chowk ensures the transition between public and private spaces and largely contributes to the thermal regulation of the whole building.

The “chowk” is not the exclusive apanache of the haveli; the house with courtyard, is an architectural device that was already used in the Indian subcontinent from 2500 BC. AD; the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa in present-day Pakistan bear proof of this.

The courtyard indeed meets the standards of the architectural manual of ancient India, the Vastu Shastra, which stipulates that all areas should radiate from a central point.

Apart from the havelis, this central structure has also been adopted by the traditional houses of Tamil Nadu; the region of Chettinad, with its splendid palatial residences, is the best witness to this.

The use of these courts and their number depends on the region of Rajasthan and its customs. The havelis of Shekhawati, for example, have two inner courtyards, the first being the public part, guests from outside the family were received there, such as businessmen and musicians who came to entertain the clients of wealthy merchants.

The second was strictly for family members and close friends. All the other rooms of the house radiate from this courtyard, those upstairs being served by a gallery that goes around the courtyard.

A social, cultural and spiritual place, the chowk is also an ingenious way of thermal regulation, which avoids large temperature differences in heating or cooling.

The high building mass all around the courtyard combined with verandas and galleries produce natural ventilation; warm air seeps into rooms during winter, and on summer evenings warm air rises and exits courtyards.

Additionally, the construction of a haveli often takes orientation into account to make the most of the sun’s heat in winter and reduce its impact in summer. Thus, in some havelis, it has been calculated that at the summer solstice the sun is almost at a right angle when it enters the courtyard, while it is much lower, around 30 degrees at the winter solstice ; this therefore allows natural light to penetrate more abundantly in the courtyard and in certain rooms on the north side. (Source: Samra M. Khan Sethi Haveli, an Indigenous Model for 21st Century ‘Green Architecture’).

The thermal insulation of the Haveli

The exterior walls

Terracotta bricks and sandstone, which were commonly used materials in havelis, are known for their high thermal inertia, i.e. they store and release heat or coolness according to changes in temperature. temperatures.

The havelis of Jaisalmer for example, as well as much of the city, are all built from yellow sandstone which is quarried locally. From there comes its nickname of “golden city”. The havelis of the Shekhawati region, on the other hand, are built with terracotta bricks and then covered with lime.

For the Rampurias havelis in Bikaner, red sandstone was chosen and for Udaipur, the city of lakes, grey-green sandstone.

Another fact, the havelis are also equipped with walls of a consequent thickness, up to 70 cm. The heavier the envelope of a building, the more it acts as a thermal reservoir: on hot days, the heat from solar radiation inwards is lessened and, during cool hours, part of the heat stored in the walls during the day is released inside.

Interior walls

The interior insulation of the walls of the havelis of Rajasthan was formerly ensured by a specific lime-based coating called ghotmakali and which few craftsmen know how to reproduce at present, the process being very long (several months) and asking for a very specific knowledge that has been lost over time.

The first step in the preparation of ghotmakali was the grinding of limestone rocks in a circular stone grinder operated by oxen, water was added mixed with fenugreek and molasses acting as a binder. This plaster was then applied to the brick walls of the haveli and allowed to dry for several months so that it could stabilize. The walls were then brushed with a mixture of shellfish powder and eggs then, when everything was dry, the walls were soaked with coconut oil. The finishing was done with agate powder (paniya bhata) from Gujarat that was rubbed on the walls to polish them and make them shine like mirrors.

This lime-based plaster also ensured good heat conduction during the winter and minimized overheating during the summer; Above all, it improved the evaporation of humidity, thus avoiding capillary rise. This last quality, breathability, is specific to lime which, due to its microporosity, has the ability to allow a large quantity of water vapor to circulate through the wall without degrading it.

Lime is also waterproof and protects the walls from bad weather; in the Shekhawati region, it was also applied to the exterior walls of havelis and then covered with sumptuous frescoes.

The roof

The roof of the havelis is generally flat, again endowed with a large thickness, about 50 cm. The roof formwork was traditionally made of wood, as is the case with the havelis of Udaipur. Since wood is a poor conductor, it limits the accumulation of heat throughout the day. For the same reason, the havelis of Shekhawati have the formwork plastered with lime.

There are also windows at the top of the ceilings of the houses which, combined with the other openings, allowed natural ventilation in the rooms.

The ventilation of the Haveli

Balconies and loggias

As we saw above, the characteristic of the Rajasthani haveli is to have corbelled balconies and loggias. If this adds no context to the aesthetics of the building, they allow above all, thanks to their depth, to minimize solar radiation in summer and winter sun to penetrate inside.

These openings were closed with thick wooden shutters or materials with low thermal capacity.

The jali

The balconies and windows of the havelis of Rajasthan are generally equipped with “Jalis”, openwork partitions made of stone or wood. This form of claustra, which is also found throughout the Maghreb under the name of “moucharabieh”, was mainly used to hide women from sight, because from these windows one can see without being seen.

The jalis also allow a good natural ventilation: the tight mesh of the partition has the effect of accelerating the passage of the wind and, in combination with the other openings of the room judiciously placed, it allows to diffuse a light breeze very appreciated during the scorching summers.

The Verandas

In the haveli, the verandas are located all around the courtyard. They have a social aspect and work as a transitional space between the exterior and the private spaces. They provide shade and protect adjoining rooms from direct sunlight.

Ceiling height

The ceiling height in a haveli can be up to 5 m. This allows hot air to rise in summer and delay the heating time thanks to the large volume of the room. If, in addition, the ceiling is equipped with a panka*, the hot summer air is eliminated via the windows and comes down again in winter to heat the residents.

*A panka is a large canvas fan suspended from the ceiling and operated by hand through a cord.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi...

4 Comments on “The Havelis of Rajasthan, bioclimatic mansions”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi Karen, thanks for your message. yes I know your artistic work, beautiful! Your are always most welcomed in Shekhawati. Please let us know when back.

namaskaram

mathini

Just love Shekhawati and the Polar haveli features in one of my works from India Song ..

I am planning another trip soon!

thanks Sulekha! Regards, Mathini

LOVED THE ARTICLE. THANKS FOR PROVIDING SUCH INFORMATION WITH THIS MUCH DETAILED STUDY.